In Delia Cai’s debut novel, family drama meets romcom meets small town politics. Central Places begins in New York and follows Audrey Zhou’s return to rural Illinois so her parents can meet her white fiancé, Ben, over the holidays. The Zhou family is one of the only non-white families in Hickory Grove, and Audrey’s return forces her to reflect on the awkwardness of her upbringing. She reconnects with old friends and an unresolved crush, Kyle, who she left behind. After speaking to Kyle as an adult, she begins to see her high school experience in a new light. Her relationship with her parents, especially her mother, comes to a head as Audrey, Ben, and Audrey’s parents are forced to spend the holiday week together and old feelings bubble to the surface again.

After reading Central Places, I couldn’t stop thinking about how Asian parents and children talk to each other, and the ways we can hurt each other in casual conversation. A relationship that is built on sacrifice and debt can, in many ways, be both unifying and straining, and can lead to a whole minefield of expectations and obligations.

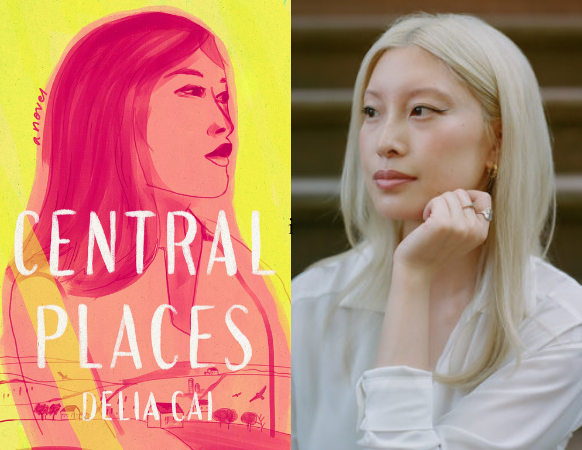

I spoke to Delia Cai, a culture writer for Vanity Fair, about growing up “in the middle of nowhere”, the dynamics between immigrant parents and their American children, and where Asian American art will be in the next ten years.

Olivia Cheng: When did you first start writing this book and what served as the inspiration for the story?

Delia Cai: It’s pretty close to my experiences growing up in Central Illinois and then moving to New York and reconsidering my upbringing with a degree of distance. I’ve been living in New York for seven years now and there was this funny period of time where every time I would go home for the holidays, it felt more and more like entering another dimension. In my twenties, going back to Dunlap, Illinois felt increasingly strange and foreign.

OC: Among many things, your novel is a love story to this rural town in Illinois, and the racial experience of growing up there. The book bursts with emotion about a Walmart supercenter and the local bar, Sullivan’s, even as the rural area often rejects or teases the Zhou family. How did you think about and achieve this balance between having longing and the politics of the post-Trump era?

DC: Growing up, I never really felt like living in Central Illinois or going to places like Sullivan’s or the Super Walmart was romantic. I felt like I lived in a soulless middle-of-nowhere suburban-rural area and there was nothing to love about that. I couldn’t wait to move to the center of the world where things mattered and life felt like living on a television show.

But my experiences going home and revisiting these places that were so central to my upbringing and realizing how much of my life and memories, the experiences of growing up, were tied to these places, I felt a fondness for the random hours I spent at Walmart with my friends or all the hours I spent at the one bar in town that everyone goes to over Thanksgiving break, because nobody had anything else to do!

I wanted to document and create a love letter toward places that you might never see on a TV show.

Tracking how my feelings changed, I wanted to honor these places. Because now that I live in New York, you do feel like you’re on a movie set, but all these places are already claimed in a way. You can’t watch TV without seeing Washington Square Park a million times with millions of people. I wanted to document and create a love letter toward places that you might never see on a TV show or on HBO or in a movie. I just had this suspicion that most people have a really strong attachment and ties to places like these that could be described as forgettable but were also so formative.

OC: Who was the audience you had in mind when you were writing this book?

DC: This sounds cheesy, but you know how everyone says, “Oh, write the book for your younger self,” but I think that’s who it was for. Also I was picturing my friends. I’m not really close with friends from my Illinois life, except for maybe one or two people. All the close people in my life came in college or after. So it felt like my life before eighteen was this box that I haven’t shown a lot of people. Like I’ve never really opened it and shown it, even to my best friends and the people closest to me. I never really knew how to totally explain it. Or my friends weren’t from small towns like that or families like that.

The novel is also an explanation for who I am to people in my life who I care about. An explanation to that hilariously loaded, stereotypical question of “Where are you from?” I wanted my friends to read it and think “Oh, this explains a lot about you.”

OC: What were your inspirations in writing this book?

DC: Reading Jenny Zhang’s Sour Hearts was a story of specificity. Here’s a cohort of young girls who grew up in a not wealthy community in Flushing. I was so blown away, because in some ways, I thought about parts of the story I related to being Chinese American and then parts that felt totally foreign. I remember thinking that the specificity of her stories were inspiring. Those stories were visceral and painful, and it seared images and scenes in my mind.

I was also reading Meg Wolitzer’s novella, The Wife. I looked at that story for structure, because it was about how a woman and her husband go on this trip and shit falls apart on the trip. It also started on a plane and I remember thinking that I should write my book that way! Those were two pivotal works.

OC: I loved Audrey’s self-interrogation and honesty about how she has contributed in her own ways to the detriment of her relationships, which is somewhat of a subversive ending given endings like Everything Everywhere All At Once, where the burden is often on the parent. Did you always know this was the dynamic when you wrote this book?

DC: I’m really glad that comes across, because that was really important to me. Writing this dovetailed with my own growth and understanding of my parents in my twenties. For a long time when you’re a young adult, you can only see and relate to things from your point of view. But there is also a layer of when you’re the child of immigrants where you’re forced from a young age to have this perspective of your parents as people who sacrificed everything for you. You’re told, “we sacrificed everything for you,” “we did this for you.” You carry that perspective and you think about how you don’t want to carry it, because it’s so much! That dynamic was something I struggled with—am I allowed to feel ungrateful, am I allowed to feel resentful knowing that every point of discomfort I’ve had doesn’t even count compared to what my parents have been through? You always have that burden.

Am I allowed to feel ungrateful or resentful knowing that every discomfort I’ve had doesn’t even compare to what my parents have been through?

But the transformation came from understanding my parents as people, especially when I got to the age they were when they came to America. Then I was like, “Oh.” I just turned 30, but my mom had me when she was 29 and when I turned 29, a lot of things made sense. If I imagined having a baby in a country where I barely spoke the language… We had this chat about how during my first few years in New York in my early twenties, I was flailing—I didn’t like my job. She would ask, “do you want to go back to school,” “do you want to get an MBA,” “do you want to go to grad school?” I remember being so angry when she would say things like that, because that wasn’t what I meant. The way I interpreted that was, “See I told you that you weren’t able to do that. Now you need to go back to Plan A.”

It took me a long time to realize that my mom was saying those things because she thought she had failed me. She thought she had set me up for success and when I was flailing, she was saying there were so many things to do, that I had so many options. She was speaking from a place of fear where she was wondering what she did to have me be out in New York and feel so alone. It was this galaxy brain moment where I really thought she was judging me, but she was just freaking out in her way. We finally had a conversation about it a few years ago, and it was the best conversation we ever had. She admitted she was scared for me and wanted me to feel like I had options. I told her I thought she was judging me for doing something wrong.

Breaking past this childlike “me” point of view and breaking past this other barrier of gratefulness to parents and superseding that on a personal level, I saw that my parents had these fears. They came to America, because they wanted to move to America. A huge part of it was inhabiting the age they were when they started making these decisions. I can understand where their mind was, because that childhood narrative is neat, but doesn’t capture the complexity of why my parents picked up and moved their lives, how hard that must have been, and all the reasons they did it.

OC: There has been some discourse in the past five years about Asian American women dating white men. Can you walk me through your thinking of making Ben white and the absence of Asian men in the book?

DC: Because I grew up in this area where there was a very small Chinese community, I didn’t know Asian-white relationships were so fraught until I moved to New York and experienced the Internet in that way. It wasn’t just my family in rural Illinois, but I felt detached from it enough and there wasn’t Reddit or anything. It just never came up, because there were not enough of us in school! As high schoolers, we were not interrogating why the guys we had crushes on were white guys. I’m so fascinated about growing up now where you can have that vocabulary and framework where you can think critically and understand the white gaze. But I just had no idea, so I was writing a dynamic I knew about and that I experienced based on relationships I had.

I think in some ways, I’m writing what I know, and I would also never want to generalize Asian American women who have dated white men, but when I looked at those relationships critically and from the benefit of being informed, I realized that when you spend your whole upbringing in a white place, you start equating whiteness with desirability and superiority. I started to understand where the appeal came from. Assimilating is how you emotionally survive. It can feel like that’s your primary drive. I don’t mean to be dramatic, but you’re thinking, “I’m just here to blend in.”

I gave all those anxieties and fears to Audrey, so it made so much sense to me to make Ben white, because she’s grown up that way. She’s someone who even into her adulthood, and I think there is a degree of internalized racism, and she’s someone who’s thinking, “I’m trying to fit in, I’m trying to survive,” and the idea of American Dream in her eyes is creating and being part of a family that is the opposite of what she had and a family that is safe. A family that is successful and can blend in and feel secure. And a white family is the secure unit pictured in our society. So that made sense for her.

I’m not trying to make a statement of Asian female-white male relationships, but I think about it a lot personally of course.

OC: A lot of modern Asian American literature revolves around really elite, high-functioning women and their immigrant family drama like Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng and Chemistry by Weike Wang. How do you think this novel contributes to this modern canon? And how do you think it rebels against it?

DC: I think it’s really funny that there’s this archetype of an Asian American woman who has her stuff together and over the course of a novel can fall apart in different ways. And it’s interesting because it speaks to the type of person who writes a book. One way to look at it is that the Asian American authors who “make it” have probably benefited from a certain kind of personality and drive, where they are thinking “I can write a novel and I can sell it.” There are a lot of forces and biases that may select for that.

When you come from an immigrant or POC background, you’re not walking around like a white guy named Tyler at an MFA program saying “The world needs my voice.” You’re coming from the mentality and background of “until I feel like I’ve earned my place, I’m not contributing my voice.” I don’t want to put words into anyone else’s mouth, but that’s how I felt so it’s funny to me that there’s this clear set of second-gen Asian American woman who have all the privileges and benefits of being in a secure place to succeed professionally and write about our experiences and have the time and energy and wherewithal to reflect on our families. My mother did not have the time and energy and wherewithal to do that.

I’ve written about this in other places, but I see that Asian American art is so much about the origin story. It’s really art created by kids of immigrants who are in a place in life where they are in a place to be making art, to be creative professionals. Of course we’re seeing this story where we’re talking about, “Here’s what it’s like to grow up in an immigrant household,” “Here’s how uptight and successful and professional I am now,” but it’s a big unpacking of this trauma.

Asian American as a term has only been around for a few decades. It’s easy to say it’s the same old story of second-gen origins, but Asian American pop culture and art can be looked at in terms of generations. We’re still at the very beginning. Now that this millennial generation really has the tools and we’re capitalizing on this moment in culture where pop culture says they are receptive to new voices and new stories, this is like some form of a draft of the Asian American story. All of the people in power who can tell stories of this scale come from a similar background to be able to do that. I can’t wait for the next generation who will tell stories about being a third or fourth generation, where the immigrant narrative is no longer part of their story.

OC: Where do you feel like Asian American art will be in the next ten years and where do you want it to be?

DC: What excites me the most is now that we have blockbusters like Shang-chi and Everything Everywhere All At Once, these tentpoles of pop culture, these big pieces of art in the imagination, we can move into stories of incredible specificity. It’s interesting because so much of the criticism around these big moments is that Shang-chi doesn’t do it for everyone. Shang-chi does not represent everyone in the Asian American diaspora, for sure. But I think that these sort of big commercial stories are great, because next we move into stories of incredible specificity.

For example, Minari is an incredibly specific story about Asian America. It’s like this family living in Arkansas and they want to farm. That is based on Lee Isaac Chung’s childhood and I love that we have that. I cannot wait for the thousands of experiences and stories, even under the rural Korean American experiences in the ‘90s, all the tiny, little different degrees of that we can explore.

Asian America’s strength and also where we have the most conflict is that it’s such an umbrella term that ultimately means nothing. We’re all bunched in together, but our grandparents hated each other. It’s wild to think that we’re all in one unit. But on the flip side, we’ve barely begun to go into the infinite swath of stories that are available and I’m really excited for that. I hope Central Places can cover a tiny pixel of all of the possible Asian American stories to be told—Chinese American growing up in Central Illinois, in the Midwest-type of experience during the emo pop-punk days. That’s one experience that I would like to commit to in the capital P project of Asian American storytelling. I can’t wait to experience all the billions of other pixels in that picture.