Author Elissa Bassist is obsessed with the patriarchy. She once texted me, “BENNY needs to go pee, and I need to go tell him he’s a GOOD BOY for PEEING, which is TYPICAL PATRIARCHAL BULLSHIT.”

Reader, Benny is a dog.

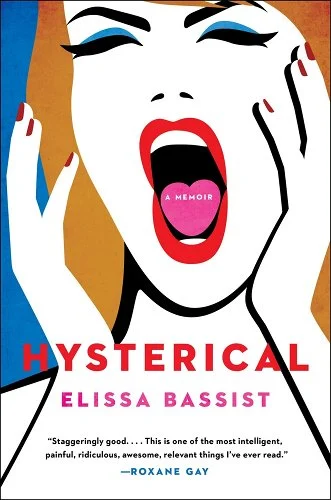

To read Elissa Bassist is to be in awe of Elissa Bassist. A self-proclaimed “aspiring witch,” Bassist’s powers are evident in Hysterical, her tragicomic memoir. Through a blend of narrative storytelling, research, and cultural criticism, she shares how a patriarchal society made her silent, which in turn made her physically ill, and how healing her body meant finding her voice. It is with this authentic voice–witty, indignant, pained, impassioned, and profound–that Bassist wrote Hysterical.

In the introduction to Hysterical, Bassist writes, “Despite the rumors it isn’t so easy to just speak up. Since women are trained to disappear while being looked at constantly, we become our first and greatest critics and censors–so, speaking up for ourselves is not how we learn English. Instead, we’re fluent in Giggle, in Question Mark, in Self-Deprecation, in Asking for It, in Miscommunication, in Bowing Down. These are all really different silences–we speak, but exclusively in compliments (‘Your sexism is so well said’) and in apologies and in all ways right.”

Hysterical is a memoir of learning (to speak, to protest, to laugh at the absurd) and unlearning (objectification, self-objectification, silence).

In Google Docs, I asked Bassist everything I’ve ever wanted to know about how, when, and why we can turn tragedy into comedy. We discussed the myth of the suffering artist, the life-saving necessity of self-advocacy, how to improve archaic fairytale plotlines, and so much more.

Sarah Garfinkel: You begin Hysterical with a perfect “Rule of Three” joke—a comedy writing technique. But the joke introduces a serious topic: the beginning of your two-year illness. How can humor help us cope with trauma? And how might it allow writers to rewrite the narrative of impossible events?

Elissa Bassist: It happens all the time: you write something, then everything changes. Plot, events, characters, how you think, whatever was seen, forged, or felt. You can just sort of redo the whole thing. And jokes are the way in–by taking us out of trauma to help us process it. Joking is alchemy; repurpose a feeling like humiliation into a joke so that humiliation means nothing.

During one memorable panic attack—when I was refreshing browser tabs in a ritual of disappointment—I had a realization. From the hardwood floor, where I’d often drop to the fetal position in a pose of clinical depression to map out my funeral, I thought, This is absurd. My thought-spirals were bonkers. Like, I was envious that a baby got more “likes” than I did. Instead of think this, I could use it, turn my thoughts into “prose,” into “art,” into jokes, which is also a way to cope, with perspective, lightheartedness, and snot. As writers and people we have two options: amplify our truth or hide it. Hiding it has zero personal, public, or medical benefits.

SG: I love the concept of joking as alchemy. Humor can make harder subject matters easier to digest. Not the actual sexism/misogyny/patriarchy, of course, but the experience of reading about these systems of oppression. Without humor, the feelings of despair might engulf us. As Mary Poppins basically sang, “Just a spoonful of funny helps the hard stuff go down.” Would you agree with MP? Can comedy help us stomach reading about trauma and also write about it?

EB: Mary Poppins nailed it. My mom also likes to say/sing, “When you laugh, the whole world laughs with you. But when you cry, you cry alone.”

People listen to a joke when they may ignore a sob story or criticism or an accusation. Laughter is an emotional reaction, and jokes trick people into hearing you, even into understanding you and what you’ve been through. Jokes get the same dark point across in a clever, entertaining way.

If you can’t say something straight (because it seems too preachy, saccharine, confessional, harrowing, or demented), then say it slant. Especially when writing trauma, we can’t always use its own words. The current words and depictions are violent and gratuitous, even trite and taboo, as if meaningless—yet they represent the most meaningful experiences. And reproducing trauma as it is is a downer and retraumatizing. So we must tell the same stories differently, with new words, new syntax—ordinary, everyday sentences can be altered, revamped, surprising—and with our own sense of humor to convey the shape and size of our singular experience.

I could not survive writing about what I write about if I didn’t make myself laugh about it.

SG: Your bio ends, “She is probably her therapist’s favorite.” For the four years I’ve known you, you have always been open about your overlapping experiences with mental health, therapy, and writing. Can you talk about when and how writing can be healthy or unhealthy?

EB: In my twenties I’d wanted to die because (I thought) I couldn’t write a book. I had a lot of stupid, shitty beliefs, like that wanting to die for one’s art was the meaning of life. And that if I had to choose between living and writing, then I’d choose writing. Since I believed in the myth of the suffering artist, I didn’t prioritize my health, as if I didn’t need it. While I did need all of the feelings to write, depression isn’t a feeling—it’s a disease to treat. When I was depressed, I just…had to be depressed. In the middle of a tragedy is not the time to write it. In the middle, you just have to survive it and get to the next inhale. Then, ten years later, you can turn it into art if you want.

SG: If tragedy plus time equals comedy, then tragedy plus no time equals…just tragedy. And a need to prioritize healing.

EB: That math checks out.

SG: For me, the fear of not being believed about physical pain, or about having too many types of pain, has at times kept me from mentioning it or seeking help and healing. From your research, will you explain why we’re conditioned to keep quiet about pain in particular?

EB: We don’t want to be perceived as annoying or difficult or demanding or whiney or dramatic or overemotional or oversensitive. We don’t want to bother or alarm or frustrate or take up space or make a scene or “play the victim.”

Also, in medical literature (and in engineering, design, politics, and everything else), the cisgender white male body is considered the human body, so white men experience pain but no one else does, and their pain and suffering represents and eclipses all pain and suffering, so uterine pain is unfathomable and “not that bad.” When “other” pain doesn’t count and should not exist, then why mention it or seek help? And isn’t there a better blowjob that you should be learning how to do?

SG: Speaking of sex, in an episode of Broad City, Ilana visits a sex therapist for a secret issue: she hasn’t orgasmed in six months. The session clarifies the issue: she lost the ability to climax after the 2016 election. The therapist comforts her and shares that since the election,“Orgasms have been down 140%.” You write about how rage and systems of oppression made you physically ill, and how you fought to reclaim your voice to release some of the pain. What advice do you have for other people trying to maintain their ongoing physical and emotional well-being?

In our culture girls learn silence, and women are routinely silenced. It’s just not cute to wear our hearts on our sleeves.

EB: Move to outer space where there is no news cycle. And when you have a secret issue, share it as soon as you’re able, with a sex therapist or other type of therapist or an acupuncturist. Sharing works. Anne Carson writes in her essay “The Gender of Sound” that in “Hellenistic and Roman times doctors recommended vocal exercises to cure all sorts of physical and psychological ailments in men, on the theory that the practice of declamation would relieve congestion in the head and correct the damage that men habitually do to themselves in daily life by using the voice for high-pitched sounds, loud shouting or aimless conversation.” Although men were treated for sounding like women (rude), the underlying idea is that to treat a problem you must treat the voice. Tell people your secrets. Scream. Vocalize. Use your voice to save your (sex) life.

SG: In your research, you learn anxiety and self-censoring is a part of girlhood. What should readers know about silence as a symptom of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder? And how does emotional pain manifest as physical pain?

EB: “Silence can be a symptom of OCD,” my psychopharmacologist explained to me, “in that you stay quiet, compulsively, because you fear, obsessively, that you won’t say things as they ‘should’ be said.”

In our culture girls learn silence, and women are routinely silenced. It’s just not cute to wear our hearts on our sleeves. Plus, our words don’t seem to matter and our voice grates and our attitude incriminates us, so silence cures us of ourselves and cures the world of us.

SG: In the book, you share your high school morning routine, which reminded me of my middle school morning routine, when I woke up early to straighten my curly hair every day. But one day I was running late and had no choice but to let the curls out, and several people assumed I had curled my “straight” hair. And then they COMPLIMENTED me on my curls. Which I’d worked so hard to heat-damage away. You write about “self-objectification” in Hysterical, which was a lightbulb moment for me. How do we unlearn it?

EB: Change happens first through awareness of how messed up everything is. I used to apologize to doctors for my unshaved legs, but after researching body hair—and writing about its bogus historical links to lunacy AND about how Gilette invented leg shaving to sell razors to women while men, their market, were at war—I stopped shaving my legs and apologizing for it. I’ve never shaved my legs “for me.” I’ve hurt my back while shaving; I’ve scratched my legs until I’ve bled 1-2 days after shaving; and I’ve been mortified by my own body. And for what? Capitalism? Or to be loved? By those who’d love me based on my leg hair and who can’t see beyond it?

Probably we should stop shaving if we want to. And delete social media. Or at least we can try to remember that our value is not in our hair.

SG: From your experience, what is your best advice for navigating our current healthcare system?

EB: My advice is to be the expert and authority on your own body. Which is easier said than done because being an advocate, an authority isn’t “nice.” Adrienne Rich calls it being “disloyal to civilization,” one that has been disloyal to us.

SG: Yes–self-advocacy is so important, especially for those privileged enough to be heard. How will you share your stories in Hysterical to support those for whom it’s not yet safe to speak out or share their stories?

EB: To quote Adrienne Rich, “When a woman tells the truth she is creating the possibility for more truth around her.” I hope I’m doing that, not only by telling the truth, but also by quoting, referencing, and citing other voices, which gives others visibility and legitimacy while acknowledging difference.

My advice is to be the expert and authority on your own body.

In Hysterical I wrote from my own experience, which is not everyone’s, just as a man’s experience isn’t mine as a woman. But feminism isn’t women vs. men, for at least two reasons. 1.) Feminism means equal rights for all, 2.) Feminism does not mean “women” because “women” in our culture stands for “middle-class+ heterosexual cis white women.” White women writers like me must include perspectives other than our own to promote and lend authority to perspectives (and humanity) other than our own.

So many voices remain unheard (suppressed, undervalued, obscured, erased), as if they aren’t required, as if they don’t influence equal rights, as if Black, Indigenous, and People of Color’s voices are marginal instead of central to feminism and feminist writing. I learned this from Rafia Zakaria book Against White Feminism: Notes on Disruption. My favorite quotation is, “The new story of feminism will be a different story from the one we know today.” Zakaria expands “feminist qualities” to include, “resilience…sense of responsibility…empathy,” and “capacity for hope.”

Personally, I plan to keep changing and keep talking about change and keep calling out biased bullshit and keep brainstorming new stories.

SG: Let’s talk about brainstorming new and improved stories. In Hysterical, you expose the problems in the plot of the 1989 Disney version of The Little Mermaid. This is a pattern among plots with classic female protagonists. Ariel: Exchanges her voice for physical changes. Belle: Exchanges her freedom for her father’s and is how many of us learned the term “Stockholm Syndrome.” Sleeping Beauty: kissed awake, in a situation in which she could in no way give consent (again, not awake). We need new fairytales, or at least updates. Instead of marrying a voiceless mermaid-out-of-water, maybe Ariel’s prince gets scuba certified so they can date in the sea? What do you think? Should we overthrow the fairytale/damsel-in-distress canon?

EB: Yes, and I think you just started the rebellion.

SG: You once said that when you moved to New York, you named your wireless network “Famous.” Will you share the backstory?

EB: I had a high self-esteem problem, which was really a low self-esteem problem. Also I believed in the law of attraction. And, like everyone else, I wanted to be famous and thought I should be for no reason. When I wasn’t famous after one month in New York, or after one decade, I needed a new goal and a new wireless network name. Now I’m humble and connect to Atria5c87b.