Earth is “well-hidden” to extraterrestrial observers using photometric microlensing to hunt for habitable planets that might support life, an international team of researchers has concluded. The findings could also help to narrow down the best areas of the galaxy to target in our own searches for extraterrestrial intelligence (SETI).

When looking for potentially inhabited planets beyond the solar system, astronomers have a variety of tools at their disposal. As it stands, by far the most successful of these has been the transit technique, which has made about 75% of all the exoplanet discoveries so far. This approach involves watching for the periodic dimming of a star’s light as a planet passes between the star and an observer on Earth.

The transit method, however, has its weaknesses; the principal one being that transits only occur for the small fraction of planets whose orbital planes are almost exactly edge-on to Earth. An alternative approach lies in photometric microlensing, which involves the gravitational lens effect that occurs when one star passes in front of another, temporarily magnifying the light from the more distant, “source” star. If the nearer star has a planet orbiting it, this can further perturb the light, leading to characteristic spikes in the observed light.

Long-distance technique

A particular advantage of the microlensing technique is that it works at relatively long distances. While other exoplanet detection methods have typically only yielded planets up to one kiloparsec (about 3200 light–years) away from Earth, the majority of the 130 exoplanets detected to date using microlensing are up to seven times that distance from Earth. Accordingly, with the Milky Way being around 30 kiloparsecs across, it is conceivable that the microlensing method might be used by other technological civilizations to detect the Earth across galactic distances.

It has long been considered that those locations from which Earth could be detectable via the transit method are themselves good candidates for targeted SETI searches – following a game theoretic, “Schelling Point” cooperation strategy for two parties looking for each other who have no means of communicating. Applying the same logic to the microlensing technique has, therefore, the potential to identify new and more distant targets for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence.

In their new study, astronomer Eamonn Kerins of the University of Manchester and his colleagues considered the photometric microlensing signal of the Earth as it would appear to other potential technologically-advanced civilizations.

Defining the EMZ

“[We] dub the regions of our galaxy from which Earth’s photometric microlensing signal is most readily observable as the ‘Earth microlensing zone’ (EMZ),” the researchers explain, adding: “The EMZ can be thought of as the microlensing analogue of the Earth Transit Zone (ETZ) from where observers see Earth transit the Sun”.

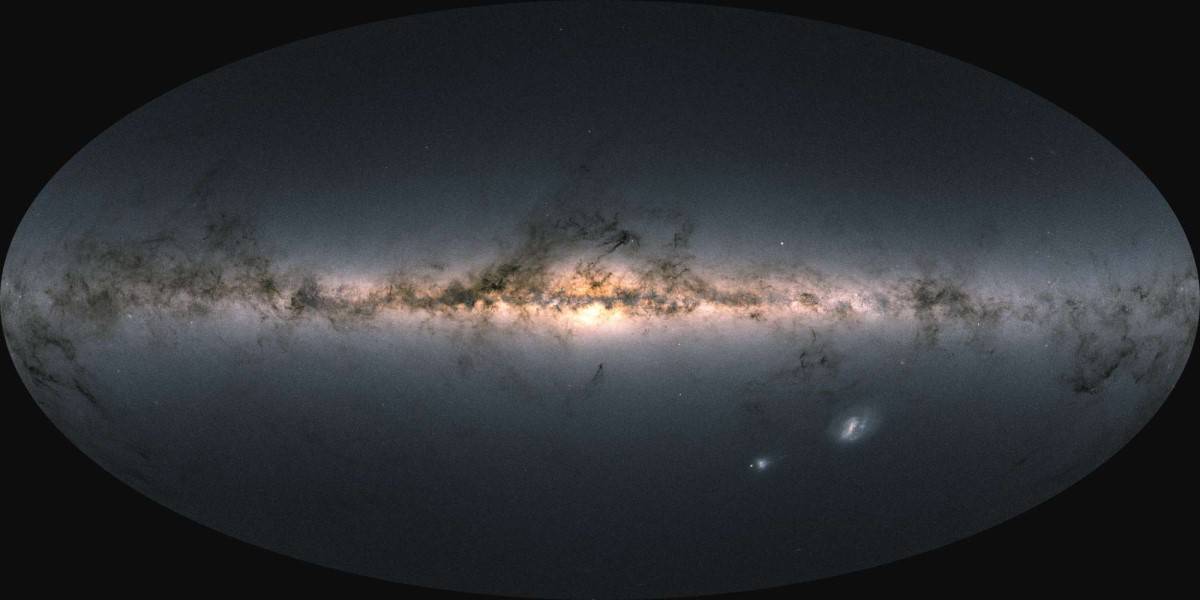

The team used data from the European Space Agency’s Gaia telescope — specifically, the instrument’s second data release (DR2), which includes information on more than 1.1 billion stars. Dividing the sky up into small areas, the team mapped out from where Earth’s microlensing signature would be visible. Even if technologically advanced alien civilizations were located around every star they studied, the team found that the total Earth discovery rate is only 14.7 observers per year across the entire sky — meaning that, assuming technological life is actually relative rare, it is “very doubtful” anyone has spotted us using microlensing.

“Earth would be a challenging target,” Kerins told Physics World, in part because it is rather too close to the Sun to give a strong lensing signal for most potential observers. Furthermore, he said, “our location 27,000 light-years from the [Milky Way’s] galactic centre is something of a blind spot for any observer using microlensing.”

Background stars needed

To have a good shot at spotting us, Kerins explained, an alien civilization would need to be positioned such that there were a lot of background stars behind us, as to give the Earth a good chance of deflecting the light from one. “The best position for an observer to be is right at the edge of our galaxy with us on a line of sight towards the galactic centre,” he noted, adding: “But there are very few stars at the edge of our galaxy and so presumably few observers.”

Defining EMZs as those areas containing the top 1% of discovery rates, optimal regions for detection appear in the Large and Small Magellanic Clouds, as well as at low galactic latitudes near the galactic centre — where there is some overlap with ETZs.

Aliens could use quantum signals to communicate with Earth

The researchers note that the direction from Earth in which potential alien civilizations would have the highest chance of detecting Earth is towards the Milky Way’s Orion–Cygnus arm, in the galactic plane. There, Earth’s microlensing probability and discovery rate values are 3.28×10−10 and 2.35×10−2 observer per year per square degree respectively.

The researchers conclude, “Overall, it seems the Earth is very dark to photometric microlensing discovery by other observers, unless they have sensitivity well beyond our own present capabilities.”

Martin Dominik, an astrophysicist from the University of St Andrews who was not involved in the present study, comments, “Clever aliens might want to use gravitational microlensing for finding candidate planets to search for other civilizations.” He adds, “It appears intriguing that they won’t be able to detect Earth transiting in front of the Sun unless they are in a narrow strip close to the ecliptic plane, which does not make it a good option to get to know each other!”

The study is described in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.