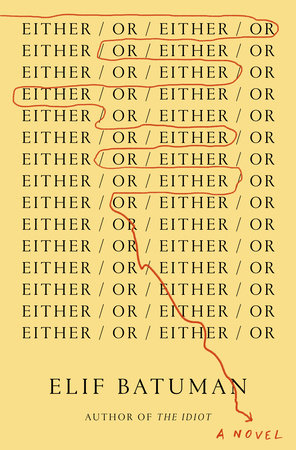

In Either/Or, Elif’s Batuman’s follow-up to The Idiot, Selin is now a sophomore in college, returning to Harvard after the summer she spent chasing her aloof crush, Ivan, to Hungary. Now Ivan has graduated and Selin is left searching for a connection to him, which, in his absence, she finds by analyzing their past interactions through the lens Freud, Breton, and Kierkegaard. The mental contortions Selin performs to apply misogynistic texts to her own heterosexual missed connections drives the novel, as does Selin’s pursuit of sexual experience and writerly insight.

Over the course of Either/Or, one actually witnesses a mind blooming, though not without misstep. Selin is funny, curious, and charming, though she is often oblivious to people’s feelings, including her own. She is ambitious yet directionless; impulsive and incautious, yet prone to overanalysis. The result is one of the most fully realized characters I have encountered in fiction, dazzling in her flaws and contractions.

All this got me thinking about the so-called “unlikable” character, a term so obtuse and tired, I loathe to evoke it here. I realized something obvious, reading Either/Or, which is that for me—and I suspect for many others—“unlikeable” actually means the opposite. Every friend I have ever loved has been unlikable in their way, stubborn, or narcissistic, or demuring, or defiant. Loving someone for their unlikeable traits is the basis of friendship, what makes it really stick. Likeable people are boring, anyway, and make for bad fiction.

Two volumes deep in Selin’s mind, not only do I like her, I feel like she and I are friends. “Selin’s going through a lot right now,” I told some actual real life friends when opting out of after-dinner drinks to go home and read. “She needs me.” Fortunately, we’re in it for the long haul. In an interview for The New Yorker, Batuman mentioned she’d like to write a novel about Selin in her 30s. I’ll be here for her then, too.

Halimah Marcus: Either/Or is a continuation of your first novel, The Idiot. Were there any expectations of a sequel that you wanted to either fulfill or subvert?

Elif Bautman: The decision to write a sequel was more about what was going on at the time and less about the decision to write a sequel. The Idiot came out right at the beginning of 2017; 2017 was #Metoo and 2018 was the Kavanaugh hearing. It was a time when people were thinking again about Anita Hill and Monica Lewinsky. And now Britney Spears. I think a lot of women were describing things that had happened to them in their past and using words that they hadn’t used before, like rape culture and patriarchy.

The literature that I was really into was super heteronormative. What role did that play for me?

I wanted to see what it was like in that space with the feelings I had, but without the vocabulary that I have now. Because when I look back, I see some of the decisions that I made or some of the things that I accepted, and I kind of wish I had been more critical, but I wasn’t. I wanted to unpack what that felt like.

HM: That’s really interesting. Your have a character that’s in this academic environment, and in theory should have access to the ideas of feminism and the attendant vocabulary.

EB: Exactly. While I was editing The Idiot, I met the woman with whom I hope to spend the rest of my life. I only dated men before that. It made me think so differently about so many parts of my identity, not just gender identity, but actually the extent to which I identified with literature, because the literature that I was really into was super heteronormative. What role did that play for me?

So I was doing a lot of reading, and the stuff I was reading was like, you know, Shulamith Firestone’s The Dialectic of Sex, where she talks about the discourse of romance and how it’s sustained by novels. And I was reading “Compulsory Heterosexuality” by Adrienne Rich, which made my head explode. “Compulsory Heterosexuality” is from 1980, and The Dialectic of Sex is from before I was born. I was like, how did I not know about these things? I had access to all of the best education anyone could have. I was curious, and yet, insofar as I knew that these things existed, they didn’t seem appealing to me. So another part of why I wanted to write this book was to show Selin being introduced in to feminist ideas. I want to help readers be able to question their own lives. What are the narratives that they might be accepting?

HM: Reading The Idiot, a lot of my excitement came from the romantic plotline between Selin and Ivan. Are they going to sleep together? What’s going to happen? And then reading Either/Or, that’s kind of taken off the table. Ivan is not physically present. He’s an absence. I almost had to retrain myself, because I picked up the book wanting a resolution to this romantic plotline. And then I realized, “Oh, no. That’s not what’s going to happen.” That was so exciting to me, because I think it’s realistic to how these kinds of infatuations—or desires, or unrequited loves, or whatever you want to call it—play out. They’re not consummated, or they remain one sided, and then that person redirects their energy. So I saw Either/Or as the story of coming out of the infatuation of The Idiot. I’m curious if you think infatuation is a fair way to characterize Selin’s feelings for Ivan.

EB: I really like how you just described it. I mean, this is something I see through after years of therapy, but the relationship with Ivan is—I don’t want to say indoctrination—but it’s really trying to inhabit a certain ideology that Selin is trying very hard to be a part of. She doesn’t quite get the point of penetrative sex, and as she does it more, she starts to understand it more. And she’s like, “Oh my God. I feel just like when I watched and understood a Shakespeare play.” It’s a feeling of self-congratulation, of finally getting the great universal thing.

The temptation is to think of yourself as having been really stupid, and yourself now as knowing a lot more. I’m just as stupid now, I just have better information.

A lot of the relationship with Ivan was about that. It’s all very exciting. But another part of what’s exciting is that she recognizes what’s happening to her as part of a plot from the kind of book that she most likes to read. I really like what you said about how it’s more realistic that that relationship wouldn’t be consummated, and how people redirect their energies. There’s a quote from André Breton about making one real person out of lots of people. When you write a novel about a first love, the tradition is to consolidate a bunch of people into one experience. In Either/Or, there’s a violin teacher, and there’s Ivan, there’s the first guy she has sex with, and then the first guy who she has a lot of sex with. They’re all different people. There’s a tendency in narrative to consolidate things. Whereas, it’s actually learning to perform a social function, over time with different people. I think that that’s a really interesting part of romantic life that we don’t really talk about, because we overvalue the connection with one individual person.

HM: There’s a point in the novel where Selin takes decisive action to have sex and things start happening. Or, in the language of the novel, the thing starts happening. Does this shift from analysis to action constitute a liberation from the compulsory heterosexuality you’re talking about?

EB: No, I don’t think so. Adrienne Rich describes it as a complex of forces that works in all of these different ways—some of them are overt and some of them are covert—to redirect women’s energies from themselves and each other and towards men. Even when Selin takes action, she’s very much taking action within the world of compulsory heterosexuality. It’s a decision that’s made in concert with and in reaction to her friendship with Svetlana. There’s even a conversation between them, where Selin’s like, wouldn’t we save a lot of time and angst if we just dated each other? And Svetlana is basically like, it doesn’t work that way; love isn’t a slumber party with your best friend. It’s like, love has to be penetration and domination. It has to be hard, and it’s childish to try to escape those things. That’s a kind of indoctrination that Svetlana and Selin do to each other and to themselves, and they do it from reading. There’s definitely a change in going from reading and thinking to actually doing things. I agree that there’s a kind of liberation in it, but I don’t think she gets outside of compulsory heterosexuality very much in this book.

HM: Svetlana at some point encourages Selin to see a therapist, and Selin says, “How was a therapist going to help me see things more clearly, when he didn’t know any of these people, and couldn’t know anything other than what was told to him, by me: a person who apparently didn’t see things clearly?”

It’s interesting to me that she is so invested in her power as a narrator of her own life that she can’t conceive that someone could see something that she didn’t intentionally reveal or try to convey. That someone can see around her. Do you see her as an unreliable narrator, or as complicating the traditional understanding of an unreliable narrator?

EB: I think the short answer to that is yes. When you get to be in your 40s, you start to think about the time in your life when you were in your teens and 20s, and you see all of these mistakes that you made. I think that’s the reason I called the first book The Idiot. The temptation is to think of yourself as having been really stupid, and yourself now as knowing a lot more. But that’s actually quite an uncharitable way of thinking about our younger selves. I’m just as stupid now, I just have better information. What I wanted to do was to go back into that state, and show why everything Selin is doing seems to her like a good idea, and seems like the only correct thing to do. But I really didn’t want to make it look like she was being stupid. I wanted to make it seem like she was drawing the correct conclusion that she had from the information that she had at the time.

An unreliable narrator, in a way, is less about the narrator than what you want the reader to do. If you’re writing an unreliable narrator, it means that you want the reader to draw a conclusion that the narrator didn’t draw. And in some basic sense, I do want the reader to not agree with everything that Selin concluded from that time. So in that sense, I think of her as unreliable.

HM: For example, in a memoir, you may have a subjective narrator, and the reader may see things that the author is not intentionally trying to present. But I think that a memoirist is going to be less aware of that possibility than a novelist, who can triangulate a relationship between the narrator, the reader, and the author. I’m wondering how you leverage that triangulation, or if you do so deliberately.

EB: One question I get asked is like, “Well, this is about a daughter of Turkish immigrants, and you’re a Turkish daughter of Turkish immigrants. So, why don’t you just write a memoir?” And I think that’s a great answer. I think of a memoir as memorializing your experience in some way. And with this book, it felt more like an imaginative exercise.

HM: As the title suggests, Selin is really into categorization. There’s Kirekegaard’s idea of ethical or the aesthetic; she talks about whether something is a form or if something is a content. Another key rubric she uses is whether something’s interesting or boring. That’s very important to her. How does this either/or, black and white ideology help her and and how does it hinder her? And more broadly, I’m curious about which parts of her personality you see as immature, if any.

EB: That’s a really good question. Today, I think that the idea of either an aesthetic versus an ethical life is deeply bankrupt. It’s something that only a really broken man would have thought of. As I was writing this book I was reading about the childhood experiences of people like Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, and they were all horribly abused. A lot of Western philosophy that we’ve inherited are the coping mechanisms of abused little boys. And we’re stuck with them now.

Simone de Beauvoir wrote “The Ethics of Ambiguity,” which says you can’t actually be free while other people are unfree. You can’t do whatever you want if you don’t have people to do it with. It’s like you have your day off and everyone else is at work. So you’re always trying to free yourself at the same time as freeing other people. It’s a project that’s ethical and aesthetic at the same time. You can’t make up one rule that always works for everything.

A lot of Western philosophy that we’ve inherited are the coping mechanisms of abused little boys. And we’re stuck with them now.

There’s no way of talking about it without sounding insufferable, but the thing that people call the hetero-patriarchy or whatever, that’s like the idea that, I can have this room and in this room, pure thought is happening and no bodily stuff is happening. There’s no garbage. Everything bad has been put somewhere else. There’s no one manufacturing anything. The manufacturing is taking place somewhere else. No cooking is happening. The cooking is being done somewhere else. And it’s just pure mind. That’s what sustains racism, sexism, classism, the pillaging of the environment—it’s this attempt to separate pure reason from everything else and denigrate the body. And that’s how misogyny happens, because men take the spirit for themselves and say, all women are the body. All this stuff strikes me as really toxic and poisonous.

Selin’s doing all the right things; she’s thinking. She’s really engaged. She’s having the right intellectual experience that a student should be having. I do think that these binaries that students get are ultimately kind of toxic, but that’s the elaborate thought structure that she has to play with. And she gets a lot from playing with it, from thinking about it, and she’s able to deconstruct it later.

I’ve been thinking about the Audre Lorde line about how you can’t use the master’s tools to take apart the master’s house. There might be ways in which that’s true. I’m sure there are. But I think there’s another sense in which, whatever tools you’ve got, those are the tools. Even if they’re bad, and even if they were used to create an edifice that ultimately you want to take down, they could still help you take it down.

HM: Ivan is very absent from this novel. Selin’s reading all these texts, like “The Seducer’s Diary,” and Freud, and she’s seeing The Usual Suspects, and she reads him into all these things. After reading “The Seducer’s Diary” she says, “The emails Ivan and I had exchanged, which had felt like something new we had invented, now seemed to have been following some kind of playbook.” And then in The Usual Suspects she relates to “the sense of discovering a total deception…the fact that deception itself was specially tailored for one other person.” All this leads her to ask her friend if Ivan is an evil person. So I’ll ask you, somewhat facetiously, is Ivan evil?

EB: No, he’s not. I actually feel strongly about that. Though it really seems to Selin that you could just be this diabolical person. The epigraph to The Idiot is this quote from Proust about how when we’re young, people seem like gods and monsters. Not to spoil, but there’s a point in the novel where Ivan writes her an email where he’s more honest than he has been, and he says something about how Selin always reminded him of his mother. And she gets this glimmer of, “What if I made Ivan feel the way that my mother made me feel sometimes?” Ivan is just as stuck in his own childhood stuff, his own disenfranchisement, his own need to prove his independence and his selfhood.

It is kind of the tragedy of straight dating dynamics; it’s a tragedy for both of them, but it’s worse for the girl. They’re looking for different things; the girl is really looking for commitment. This isn’t in the finished version, but in an earlier draft Selin reads that horrible book, Men Are From Mars, Women Are From Venus. The girls are looking for this kind of connection and love and the boys are looking for some kind of adventure and specifically to not get tied down. And for the girls, the ability to have a boy commit and be the boyfriend is what gives her an ability to save face in front of her friends and to not feel ashamed that she’s being used. And for the boy, the ability to not be tied down and to not have committed to something is what enables him to save face among his friends. It’s this huge starting obstacle that every straight couple eventually gets over in some way. But what a big stumbling block.