WASHINGTON — The European Space Agency has issued contracts to two European industry groups to begin concept studies of lunar satellite systems that would provide communications and navigation services.

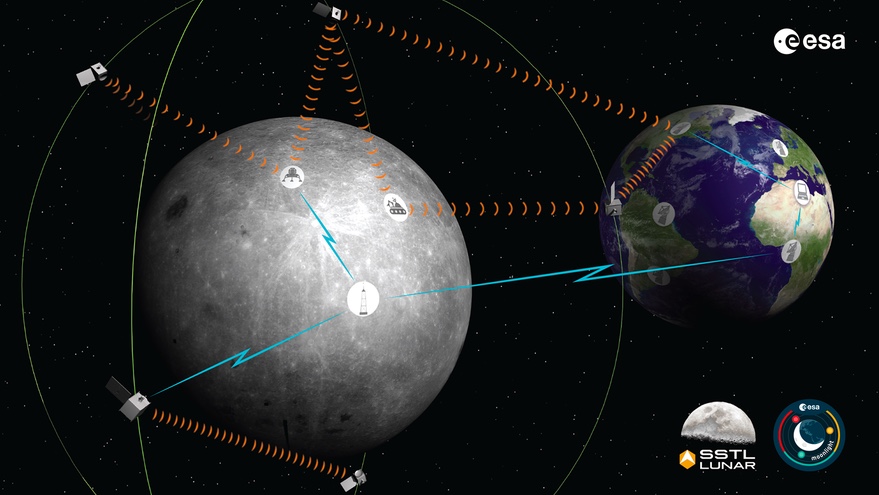

ESA announced the awards May 20 to two consortia, one led by Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. (SSTL) and the other by Telespazio, to begin studies for the agency’s Moonlight initiative, which proposes to place a network of spacecraft around the moon to support human and robotic exploration there.

Those satellite constellations would ultimately be available to both government and commercial lunar missions, potentially as a commercial service. Such a network, ESA officials said, could make lunar missions easier and less expensive to develop.

“The value proposition is, if you have an interest in putting a device on the moon, you can offload a lot of your current navigation subsystem equipment,” said Paul Verhoef, ESA’s director of navigation, during a media briefing about the awards. “This weight and this volume can then be used to put additional instruments on your lander and bring that to the moon. On the other hand, the savings you have from the cost of that would be used to pay for the navigation service.”

Neither ESA nor the two industry groups disclosed the value of the contracts, and ESA officials, asked about that at the briefing, said they did not know the value. One industry source described the contracts as being worth a few million euros each.

David Parker, ESA’s director of human and robotic exploration, said these are Phase A/B1 contracts in agency terminology. “This means the feasibility of the system but also the business case,” he said. “A level of design definition that convinces us that the system can be built.”

Those studies, he said, will run for 12 to 18 months, concluding in time for ESA to seek funding for later phases of Moonlight at its next ministerial meeting in late 2022. “If that was the way forward, the project could start full steam ahead at the beginning of 2023 to ensure it’s operational within four or five years.”

The two consortia are in competition with each other, said Elodie Viau, ESA director of telecommunications and integrated applications, but suggested that besides selecting one of the groups for further development, there could be a “reorganization” of the groups.

The SSTL-led group includes satellite manufacturer Airbus, satellite operator SES, ground station companies KSAT and Goonhilly Earth Station, and satellite navigation company GMV-NSL. The Telespazio-led group includes operators Inmarsat and Hispasat, manufacturers Thales Alenia Space and OHB Systems, space technology company MDA and several Italian companies and universities.

SSTL is already working on a single lunar communications satellite, called Lunar Pathfinder, scheduled for launch in 2024 for an eight-year mission. That satellite will operate in a highly elliptical orbit optimized to support missions at the south polar regions of the moon, an area of interest for several robotic landers as well as NASA’s Artemis program. Lunar Pathfinder will communicate with lunar missions at UHF and S-band frequencies and relay them to Earth at X-band.

“We’re creating this shared communications and navigation network for the moon that we believe will undoubtedly act as a catalyst to inspire more exploration missions,” Phil Brownett, managing director of SSTL, said at the briefing. “We see it as significantly reducing the cost and complexity of subsequent individual expeditions.”

ESA is not alone in studying lunar communications and navigation networks. NASA is in the early phases of a concept called LunaNet that would place a network of satellites around the moon to support Artemis and other lunar missions.

“Our philosophy is that each mission should not have to create its own communications and navigation infrastructure,” NASA’s Andy Petro said of LunaNet at a meeting of a Space Studies Board committee April 9. “We see having an infrastructure to supply those services lowers the barrier to entry for new missions.”

Petro said that LunaNet is still in an early stage of formulation, with NASA studying the acquisition strategy for it. He said it was unlikely that NASA itself would operate the network, instead using public private partnerships or service contracts. “I don’t expect it to necessarily be the type of traditional development and procurement that we’ve done in other cases.”

“NASA is fully aware of Moonlight,” Parker said at the ESA briefing. “They have an overall vision for lunar communications but, as far as I know, no specific industrial studies. I think we’re the first to go forward with the idea of a commercial service delivery.”

Having more than one network at the moon could provide redundancy, ESA’s Verhoef noted. “Certainly for the navigation part, if there are more systems, all of them are possible to be used,” he said, arguing for interoperability among those lunar navigation networks similar to that with terrestrial satellite navigation networks. “In the end, we are talking about the safety of life of astronauts, so there is going to be an interest to have two systems in order to make sure that, if there is a problem with one of the systems, the other can take over.”