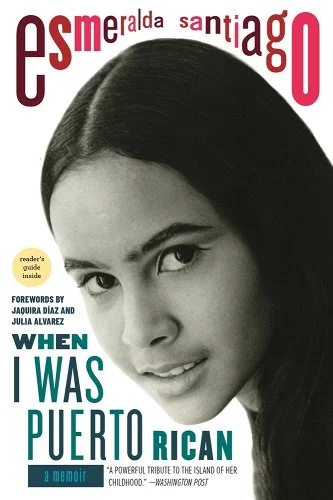

Esmeralda Santiago’s book When I Was Puerto Rican debuted 30 years ago. This memoir introduced us to Negi (Santiago), a pre-teen with a captivating voice who chronicles her life in rural Puerto Rico in the 1950s. In Santiago’s own words, the memoir captures a world that no longer exists in Puerto Rico.

We watch Negi grow from four years old to becoming a teenager, from living in rural Puerto Rico to living in Brooklyn, and from helping rear her younger siblings to having to take on the responsibility of learning English. We watch the dissolution of her parents’ relationship, constant dislocation, and how the United States transgresses into their lives by innocuous means like a nutrition guide and by a nasty concoction of powder milk and peanut butter. But we also see Negi’s curiosity, her incessant questions to her poet father, her defiance, her love of storytelling, and how Negi and her family survive. They keep going, and this memoir ends with a fairy tale ending, which is what any reader would want for Negi after reading this endearing and enduring memoir.

I interviewed Santiago via Zoom. Our conversation took frequent diversions which gave us insight into the world of working-class people in New York in the ‘60s; her ordinary, but extraordinary, mother; and how as we grow, we learn to forgive our parents and all the uprootings we may have suffered.

Ivelisse Rodriguez: All three of your memoirs, When I Was Puerto Rican, Almost a Woman, and The Turkish Lover, are being reissued, along with audio versions in English and Spanish narrated by you. What does it mean to you as a writer to have written books that have had such longevity to the extent that 30th anniversary editions are being published?

Esmeralda Santiago: I was thrilled to hear that the book has been in print for 30 years and being taught in schools across the United States and in some foreign countries. We often think our lives are so singular. But in many ways, there are so many points of connection between us and other people who are completely unlike us. This is what I love about memoir—you can write about your experience in rural Puerto Rico in the 1950s, and somebody in Moscow can get something out of it. It’s fantastic.

IR: What was the impetus to write your memoirs?

ES: I started writing from a place where I felt invisible in the United States. I had a child, and I was worried that my child would not know anything about his mother. We lived in suburban Massachusetts, and I was pretty sure I was the only Puerto Rican in this town. So I began to write because I didn’t want to forget the experience of how I grew up, and I wanted to pass it on to my children, so that they knew about it, even though they were going to have a very, very different life from the one that I had.

I started writing from a place where I felt invisible in the United States.

Also, when I was in Brooklyn, I found myself learning about the United States by reading the literature that I came across. But then at a certain point, I realized, wait a second, I’m not in this culture. None of the books are about me. And that’s when my need to write about people awakened, so that I would not be the only one going through this experience.

And when I was about 16 or 17 years old, the famous, wonderful poet, writer, essayist Langston Hughes came to my high school. He came to do a presentation about his book and to talk about being a writer. And I just remember he was just so very handsome, he was dressed beautifully, and he was this Black man with such dignity, and a beautiful voice, and he talked about his writing and about how he hadn’t seen himself in literature either.

IR: Oh my God, that’s amazing that you got to meet Langston Hughes!

ES: It was just sheer luck that on that day, I didn’t have to take my mother to welfare, or I wasn’t sick, or something. I happened to be there when this man was there with an important message for all of us. This message of writing yourself into the literature really, really stuck with me to the point where when I met people who were at his presentation, they don’t remember that event until I remind them. It was like he came from this place in Harlem to talk to me, who could barely understand English. But I literally went from school to the library and took a stack of all his books that I could find and read them all. He showed me the way to write about myself in literature, and I am forever grateful to him and to that event and to whoever organized it.

IR: Though there were hardships in your childhood, one of the things that always stood out to me about your book is how endearing it is, and how lovingly you recreate your childhood in Puerto Rico. How do you, as a writer, hold the hardships of the past alongside the love for the past?

ES: I decided to not write it from the perspective of an adult because an adult makes all kinds of assumptions about the past; we visit the past in a way that’s more comfortable for us. So, I decided I was just going to try and inhabit the child at that stage and detail what that child would have experienced and would have noticed at that age. And so, by doing that, it made it possible for me to really tell a story rather than trying to make sense of the past or turn the writing into therapy. By limiting the point of view to the child, I thought the reader would have a much more immediate connection to the experience.

IR: I was wondering about the courage to represent your mother as you saw her when you were young. She was doling out cocotazos and frequently fighting with your father. At first, she seems angry, but as we keep reading, we see what she was going through.

ES: In When I Was Puerto Rican, I just didn’t want to add the knowledge that I now have as an adult to this child’s head. As a child, all you know is what you’re seeing. For example, as a child, I didn’t have any idea about infidelity. My mother just said your dad is with other women. As a child, you can’t even envision what that means, but obviously it’s a bad thing. If you read my other memoirs, the character of Esmeralda continues to mature intellectually, so she’s better able to make those kinds of connections later on. It requires experience in life for you to understand those kinds of things.

Plus, I didn’t want to subject my parents to psychologizing. It was a literary decision that made it possible for me to avoid playing Dr. Freud.

IR: How did your mother react to the book?

ES: At some of my events, my mother would answer that question by saying, “You know, everybody talks about this book as if this is about Esmeralda, but this book is about me.” So, she understood that she was the hero in this book. Even though I’m the main protagonist, she really is the person who makes things happen for the character. And then my dad said he loved being the villain in this book.

This story was about people like us: jíbaros.

The rest of my family has been like her. They’ve been very, very supportive, encouraging and generous about not challenging any of the things that I’ve said because they all understand this is the way I saw things, even though they might have had a different experience. I’m the eldest of 11, so we all say that we each had a different mother. The more experience she had as a mother, the more she learned and became a different person.

My mother also thought it was great that this story was about people like us: jíbaros. I think my parents really understood that I picked up on something that had not been done in literature. There really wasn’t a lot of writing about the jíbaros from the perspective of the jíbaros. The books that existed about that community were written by people from places like Barcelona. They did not live that life, but I lived it. So, I wrote When I Was Puerto Rican from the perspective of a jíbara. And my mother really appreciated that. She said my book really sounds like the way it was. My parents were both smart people, and they liked reading, and they liked seeing themselves in literature.

IR: That’s an excellent point about the jíbaro experience and who was writing about it. I am glad you pointed out that this was a gap you were filling in literature by Puerto Ricans. Also, it is interesting to see how you come to understand yourself as a jíbara. Early in the text, when you’re living in Macún, you wonder what a jíbaro is, and you are told these people who live in the countryside with all there mores are nothing to aspire to. But when you moved to Santurce, you were called a jíbara, so you had to see yourself in a new way.

This is the beginning of a series of rejections and becomings that you had to endure for the rest of your life. How did this help you transition to living in Brooklyn?

ES: Well, I think when you live in chaos, you get used to living in chaos. You find ways to deal with the chaos around, for example, the chaos of being in one-room apartments with eight, nine, ten, 12, 15 people. I can’t control that. That was all we could afford. I really understood that. I was very empathetic to my mother’s struggles. In fact, at a very early age, even though I was angry at her for bringing me to New York, and not going back to Puerto Rico immediately when Raymond was fine about a year later, I really understood that a lot of what was happening around us was outside of our control, my mother’s too. I remember she would work in a sweatshop for a week, and on Friday when she got to work, it would be closed because they didn’t want to pay the workers. This happened to her all the time, to the point that she then only worked in the sweatshops where they would pay at the end of the day. She learned how to fight for herself. She had to make these transitions as well.

We were all going through these transitions: learning language, getting used to the climate, and more. All those kinds of challenges were happening to all of us at the same time. But of course, my mother had the biggest responsibility because she had all these children.

IR: One of those challenges was learning English, and this led to a fight with your mother when you came home late from the library. She accused you of thinking you could do whatever you wanted because you spoke English. In what ways did learning how to speak English give you freedom to develop a self?

ES: My mother really just drilled it into me that I had to learn English when we came to the United States because, first of all, she needed a translator. I was the eldest, and I was the most willing because I was always reading. I had to learn it fast because she couldn’t do it. And no one in our immediate family was remotely bilingual. So, I knew that this was my task. I had to learn it quickly, and I had to learn it well enough to be able to help my mom because that was the only way that I could as a little kid. I didn’t resent it. In fact, I thought it was great. I love learning. I came to the United States in 8th grade. By the time I graduated, I entered grade nine, and I was reading at a 10th grade level in English. But I couldn’t pronounce things. I couldn’t speak it. I mean, I could have, but I would have mispronounced everything. So I was very silent and quiet the first two or three years that I was in school, but I aced all my exams. I realized then that that gave me power. When translating for my mom, for example, I realized I couldn’t mess up the translation of application forms or mess up translating for a kid who’s convulsing.

The culture was harder for me. I was a teenager who wanted to be like every other girl. And, according to my mother, I was not like any other teenager because I was Puerto Rican.

IR: In Nicholsa Mohr’s Nilda, another classic book written by a Puerto Rican woman about girlhood, Nilda’s mother is giving Nilda consejos on her death bed. Among the advice the mom gives is that she warns Nilda that men will leave her with a bunch of children, and then she will have to go on welfare. This is, at times, what happens to your mother. Nilda’s mom continues with her advice and tells Nilda to always keep something for herself that is all hers and that if she cannot see beyond being a mother, then life was not worth it. What do you think are the things that your mother kept for herself that brought her joy?

ES: First, I think my mother really kept a lot of stuff from us. A lot. And I don’t know just how much. Maybe I know 4.5% of what she went through from the interviews that I did with her. And even that information was absolutely horrific to me. I know that I will never know what all her sacrifices were.

But in terms of what brought her joy, she was a child of the depression, so she just loved feeding the people she loved and making sure that they were nourished. She loved dancing. She loved music. She wasn’t a swimmer, but she liked going to the beach just to feel the salt air. She loved dressing nicely. When you’re raised very poor, you have longings for certain things. When my siblings and I all had jobs and could make money, we gave her gifts that would bring her joy.

She was somebody who was full of joy in many ways in the midst of chaos, tragedy, hard work, and humiliations. She always found a way to smile and to find joy in something. And I think she passed that on to all of her children.

IR: That’s really heartwarming—that you were able to participate in giving her that joy.

In When I was Puerto Rican, before you get to Brooklyn, you write that you did not forgive the uprooting. At this stage in your life, have you forgiven the uprooting of coming to the continental U.S.?

ES: Yeah, I guess I have. I’m not a person for regrets. As a child, I was very angry for years because I didn’t understand what had happened. Nobody explains it to you when parents break up. And then many, many years later, as I matured, as I learned, and as I knew my parents better, I understood that they really did the best that they could with what they had. Once I understood that adults do things for reasons that children cannot understand until they’re adults, then it was really easy for me to forgive.

In Puerto Rico, the doctors were ready to amputate my brother Raymond’s foot. My grandmother and all of my mother’s aunts and uncles were in New York, so they encouraged her to get a second opinion in the United States. And, the doctors in the U.S. said they could save his foot. She came back to Puerto Rico, and she asked my dad if he would go with us. My father and his family were very independence-minded, anti-imperialism, and anti-colonialism. So he refused. My mother was forced to make a choice between her children or her man. Even though they were always fighting, they really did love each other. She had to make that decision, and she chose her children. She knew that she would have to move to New York, at least for a year or two, in order to make sure that Raymond was completely well. I think once she was here, she realized, it’s equally hard here, but I have more help here. Seven years later, she did go back to Puerto Rico with all the kids that were left. And it was just me and Elsa who were in the United States. We were both studying, so we didn’t want to go back at the time.

Both my parents have passed, and I think they should be and must be very proud of the children that they had because we are two or three steps economically from where they were at their best. That was something that they wanted for us. They wanted us not to struggle quite so much. We still struggle, but the struggles are different. We live in nicer neighborhoods than we did when we were growing up. So, all their sacrifices, dreams, and aspirations did come about. I’m very proud of the work that my parents did with us.

Read the original article here