WASHINGTON — As the Artemis 1 mission nears its conclusion, European Space Agency and industry officials praised the performance of the Orion spacecraft’s service module, which some see as a step towards a European crewed spacecraft.

The Artemis 1 mission is set to conclude Dec. 11 with the reentry and splashdown of the Orion crew capsule, shortly after it separates from the European Service Module. That module provided power, propulsion and other services for the spacecraft since its Nov. 16 launch.

“We are coming towards the end of what you might think of as a 100-meter race that’s followed a marathon,” said David Parker, ESA’s director for human and robotic exploration, during a Dec. 9 briefing. “The marathon was the 10 years of effort and preparation needed to build and prepare the first European Service Module for its journey to the moon and back again, and 100-meter race has been that actual mission itself.”

During that 100-meter sprint, the service module has not broken stride. “The mission has gone really perfect from our point of view,” said Ralf Zimmermann, head of moon programs and the Orion European Service Module at Airbus, the prime contractor for the module. “We have absolutely flown a perfect mission so far.”

There have been minor issues with the module, he noted, “but nothing mission critical.” One persistent issue has been with devices called latching current limiters in one part of the spacecraft’s power system. Those devices, similar to circuit breakers, have opened at least 17 times during the course of the mission without being commanded to do so, NASA officials said at a Dec. 8 briefing, but have not significantly affected spacecraft operations.

“It’s not a big deal because they can be recommanded on,” said Philippe Deloo, ESA program manager for the service module. “We don’t have an idea of what is the root cause. We are investigating, looking at all possible options.”

One possibility, he said, is that electromagnetic interference or noise in the power system is causing the latching current limiters to open. Another possibility is they are being affected by transmissions from spacecraft antennas. Engineers are doing as much testing as they can before the end of the mission to identify the cause. “This is going to be a difficult one to troubleshoot.”

Zimmermann emphasized the issue was not serious. “When they open uncommanded, the effect on the mission is not that big,” he said, noting it affects only one of eight power lines on the spacecraft. “It is a glitch, not a mission-critical failure.”

Other parts of the European Service Module have exceeded expectations. The spacecraft is producing more power than expected, yet using less power than planned. Deloo said the reduced power consumption is, in turn, linked to the spacecraft dissipating less heat than expected, meaning it has to use heaters less frequently to maintain its proper temperature. “This is one of the major lessons learned.”

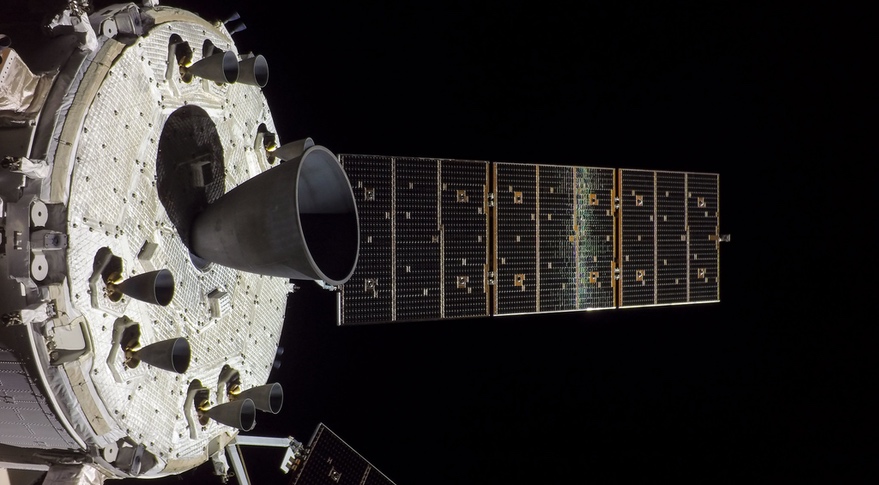

The service module has also produced many of the stunning images and video the mission has returned, thanks to GoPro cameras mounted on the tips of each of the four solar arrays. “We are calling them now four selfie sticks,” quipped Matthias Gronowski, chief engineer for the European Service Module at Airbus.

The Artemis 1 mission, and excellent performance of its service modules, comes as some in Europe advocate for ESA to develop its own human spaceflight capability. Human spaceflight was one of the long-term “inspirator” concepts endorsed by ESA member states a year ago, and remains a topic of debate in Europe.

“We have to see how far politicians are willing to look into this,” ESA Director General Josef Aschbacher said in a Dec. 1 speech at a Space Transportation Association luncheon here, noting the topic would come up at a second European “space summit” scheduled for late 2023. “Does Europe want to be more independent, more autonomous in human space transportation?”

“In terms of technical capability, can Europe build a human-rated space vehicle? I don’t doubt it,” Parker said, citing the success not just of the Artemis 1 mission but work on International Space Station modules and elements of the future lunar Gateway. What would be needed, he said, was experience in end-to-end operations of a crew spacecraft and development of safety systems, like a launch abort system, as well as a human-rated launch vehicle.

During the International Astronautical Congress in September, ArianeGroup released a concept for a vehicle called Smart Upper Stage for Innovative Exploration (SUSIE). The vehicle is designed to be a new, reusable upper stage for the Ariane 6 rocket, but could be used as a cargo and crew transportation vehicle. Morena Bernardini, head of strategy and innovation at ArianeGroup, said in an interview at the conference that a cargo version of SUSIE could be ready as soon as 2030 followed by a crewed version “immediately after.”

At the briefing, Zimmerman suggested Airbus was more interested in working with others, along the lines of the existing partnership on Orion, than developing a European crewed vehicle. “We need to unite forces and share the costs,” he said, noting he was offering his personal opinion. “This is, to me, much more important than saying its Germany, France, England or Europe in total against the Americans.”

Parker said the success of the service module shows ESA is ready for the next phases of Artemis. “We learned that we can send a crew-rated capsule to the moon and back again on its first flight, and that means it gives us a lot of confidence to go forward in the next steps in Artemis.”

ESA has a contract with Airbus to produce service modules through Artemis 6, at a total value of a little more than two billion euros. ESA’s member states approved plans to produce three more service modules at November’s ministerial meeting, and Parker said the agency will get those under contract some time in 2023.

The Artemis 1 service module will end its mission about 40 minutes before splashdown when it separates from the crew capsule shortly before reentry. The service module will burn up in the atmosphere, with any surviving pieces falling into the Pacific Ocean west of Peru.

“It’s a little sad, but we’ve accomplished the mission,” Zimmerman said of the impending demise of the service module. “We are proud of all that has happened.”

“You cannot be sad when you accomplish your mission,” Deloo said. “Everything has a life. The end of the life is part of the life. As long as the life has been successful, this is a great success. So, I’m happy about it.”