Stereo Instructions by M.D. McIntyre

Everything I know about the dead I learned from Beetlejuice.

I didn’t see Beetlejuice in theaters when it was released in 1988, but it became a favorite a few years later when I rented it for sleepovers and watched it on cable tv. Back then I drank Vernor’s Ginger Ale in the basement of our 1912 East Coast colonial, watching the movie on a boxy tv with bunny ear antennas. It was an age when I lived perpetually in a world of my own imagination. It was before the frequency of the grown-up world came in clearly, when there was still interference, the soft hum of other stations buzzing along beside me.

As a kid, the movie’s world—one in which the characters were both the living and the dead—seemed more accurate than a world that only contained the living. In the first few years of my life, I lost my aunt, my grandmother, and my grandfather. It seemed to me that the death of a close relative was an annual event, and each fall when the wind picked up, I wondered who would be next.

The first was my aunt. She lived only a few blocks away and died of cancer when I was three. Then my grandmother—heartbroken by the loss of her oldest daughter, died of a different cancer. Then my father’s father passed a year after that. I don’t remember any of these relatives very well, I only remember what everyone else said about them. Other people’s memories put my aunt in the garden, on our brick patio, in the kitchen cooking for a party, on the Queen Elizabeth II floating across the Atlantic. My father’s father was out on the golf course in the summer, in the Elk’s Lodge with an Old Fashioned in the winter. My grandmother, in a floral housecoat, was sitting in her antique wingback chair poring over her newspaper. For me, this is where they are forever.

It would never have occurred to me that years later my son might have his own hauntings.

It would never have occurred to me that years later my son might have his own hauntings. But just before he turned three, his father died by suicide. I worried he would feel all those things I felt when I was little: talking to the dead alone in my bedroom, trying to imagine what it would be like if they were still here, worried who else I might lose in the coming years.

As a preschooler my son regularly asked me if his dad could see him or hear him. He wanted to know where he was. He asked these questions in the car on the way home, at night before he fell asleep. He asked them repeatedly for years, because his mind and memory were only just growing into a general comprehension of our existence. I read him books about grief and loss. They were so hard to get through. He didn’t like hearing about death any more than I liked reading about it. Or maybe he was feeding off my own body, seized with emotion, as I read “he’s never coming back” my son’s hands would reach out and close the book or try to push it to the floor. As a kid, I’d wanted the grownups around me to talk about the losses, but when I had to comfort my own son, facing the heartache head on, being strong and sensitive for him, the task was incredibly hard.

I knew from experience what not to do when my son lost his father. And yet, I struggled. It is easier to pretend nothing bad happened. It is easier to shield them from heartache and difficult conversations. I had to pay attention to who my kid is and how he takes it all in. I had to adjust to his personality, which was different than my personality. I had to grieve and show him it was okay to be so sad, and then show him we didn’t need to be that way all the time.

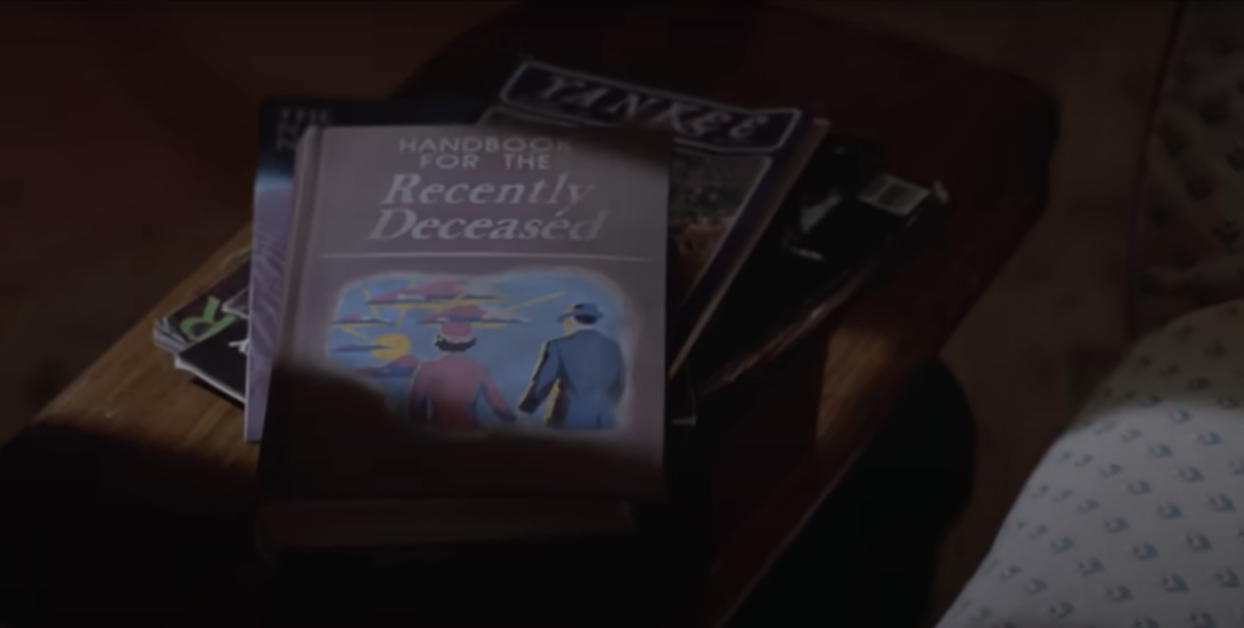

I spent a lot of my early years wishing the dead back to life. They were always on my mind, always the center of some story being told around the dinner table. The collective family grief was palpable. In Beetlejuice, there are rules for getting used to the afterlife: The Handbook for the Recently Deceased. This is what I wanted too, a guide to make sense of the losses in my life, a way to navigate a world where the recently deceased still felt so close by, staring at me from picture frames on the stairway every morning, floating over the table as my parents talked at dinner. When my son lost his father, I knew that to get us through it, I had to revisit everything I’d internalized as a kid about grief and death. I looked again toward those early experiences in my family, and of course, to the rules I learned from Beetlejuice.

Rule No. 1. Ghosts inhabit the places they were.

In Beetlejuice, Alec Baldwin’s Adam Maitland and Geena Davis’s Barbara Maitland die early in the movie and quickly discover they cannot leave their idyllic Connecticut country house. Or more precisely, they might be eaten by giant monstrous sandworms in an alternate universe if they try to leave. Watching Adam and Barbara survive the vicious sandworms by making it safely into their house, safe from the vicious sandworms, made me worry a little less about the close friends and relatives my family had lost. Instead of buried in the graveyard, I preferred to imagine they were also in the attic tidying up like the Maitlands.

Though not formally espoused by the characters, the movie made it clear to me that ghosts were often trapped where they had lived. This rule felt true, reinforced by the countless hours of Unsolved Mysteries I watched as a kid where there were stories about a little boy who haunted the hallway where he played marbles, a high schooler who couldn’t leave the football field, a solider on a hill in a blue uniform with bullet holes and a baton. Like the ghosts in those tales, The Maitlands stay in their home, stuck in the attic once the rest of their house is inhabited by its new, living tenants, the Deetz family.

Twenty years after the movie came out, I was forced again to think about where the dead might spend their days when I finally got out on the path where my son’s father died. Simon ended it all on a beautiful Oak Tree that had one giant branch extending out over a creek. Initially, I hesitated to go there—the park, the path, the tree. Even more, I was hesitant to take our young son. Although I had no plans to tell him “This is the place,” I mostly worried he would just sense something is off. But some friends who live right next to that park insisted. When I was there, I looked for all the cues of my ghost and didn’t feel him at all. Instead, I feel him everywhere else.

Rule No. 2. The living won’t usually see the dead.

Barbara reads the second rule from The Handbook for the Recently Deceased just before Lydia Deetz, the iconic goth girl played by a young Winona Ryder, notices them up in the attic window. The Handbook explains: The living tend to ignore the strange and unusual. But it doesn’t mean they can’t sense the unnatural. When Lydia sees them and says, “I myself am strange and unusual,” she is all of us ghost-carrying girls at fifteen.

It happens again and again—people do see the strange and unusual. Simon’s Aunt Joanie worked second shift at the Dollar Store and spent Sundays delivering breakfast to her elderly parents. She didn’t seem one for fantasies, but she told us that she saw a feather floating over the pew at the start of Simon’s funeral service, the one held in his rural hometown on the Ohio River. She said it was a sign. Everyone stood around nodding next to the large flower displays and the black box holding his ashes. I nodded too—to be polite. Was Simon really dropping feathers to say hi? Was Simon actually the feather? What I really wanted to know, in the years after Simon died, was how he was so many places at once. I felt him all over the city we lived in. But it didn’t happen right away. It took months for him to materialize in some form or another, to start to feel close. In the first few weeks after he passed, I couldn’t find him at all. It was terrifying, because I have never needed to find someone, to hear a voice, as much as I did in the hours and days after I knew I could never find him again.

Rule No. 3. The living may try to erase the dead.

When Lydia’s stepmother, Delia Deetz, played in a wonderfully extravagant way by Cathrine O’Hara, begins renovations on the house with her sidekick Otho, Barbara and Adam can do nothing but watch helplessly. It’s their worst nightmare (after their own deaths of course): this new family tearing apart everything they created. The living erasing the dead.

For Lydia, moving to a shiny-white-New-England-model-home-covered-bridge-church-bell-town was already an erasure of its own. In the movie her mother is mysteriously absent, but Lydia is dressed in all black with veil—the death is implied. In Beetlejuice, The Musical, Lydia says as much: that she wants to go back to their old home where all of their stuff is and where everything reminds her of her dead mother. For a generation of girls growing up in the 90s, the ones who felt any kind of chronic loneliness and loss, those of us identifying as the continuously bereaved, she was the quintessence of the lost girl. She wore her grief. She took pictures of ghosts. Her stepmother Delia makes fun of her behind her back, and proceeds without caution, dismissing her easily. Her father tries to ignore it, tries to cheer her up.

Tim Burton got this part right: grief, especially in children, is most often ignored. Dead family members get packed up and put away, and children are left feeling they can’t get close to them if they need to. This was often how I felt when I was young. In my family, it wasn’t so much that the dead were off limits as a topic, but that no one would have thought to discuss them with me, a child who probably didn’t remember them very well. It was much easier to imagine I wasn’t bothered by their absence.

This thought was echoed by well-meaning people when my son lost his father: He won’t remember him, they said, as if it was a blessing. But everything I’ve learned in the years since my son’s father died tells me that my son does have memories of his father: those early, intuitive, somatic memories. At age one, you might remember something for a few hours or a few weeks. At two, you might remember something for a few years, before your mind places them in a file that can no longer be recalled because you are building so many new files it can’t yet keep track. But those memories are still there. Just as we hold traumatic experiences in our body, we also hold emotions and memories. The prevailing wisdom until very recently was that those little kids would not grieve even their closest relatives if they didn’t remember them. But it isn’t necessarily true.

It was during the montage of home destruction, as our antagonists, Lydia’s step-mother and her friend Otho, ransack the house, that I began a lifelong desire to hang on to every little thing. I took pictures at every family event so I would be able to remember everything and everyone forever. I didn’t want to let go, and still don’t. I prefer the haunting to their absence, and my home is filled with the small things my aunt, and grandparents, and Simon have left behind—pictures, vases, books, report cards from the 1940s, newspaper clippings. Their small glass candy dishes are now full of my son’s Legos. It is cluttered, and I have a very nice therapist who helps me understand why I can’t part with these things without great distress.

What I should have learned is that interior design is not an exorcism.

The losses made me cling to whatever I could hang onto. Tangible items. I didn’t want my son to have all those hangups. The message I swallowed whole when I first watched that montage was that if you try to dispel someone too quickly, they will haunt you more than if you left their things just as they remembered. But what I should have learned is that interior design is not an exorcism. You can take everything out, every little piece that belonged to the dead, their flower-patterned wallpaper, and their stained oak bureau and the country kitchen, and move in your fire-engine-red bar and your stone slab table and your monsters—imagined or the kind made of clay— and even then, you will still find the dead there. Perhaps looking and longing for everything you took away.

What I clung to were the items, when what I should have seen at the end, what I was always trying to show my son, was the way they never leave you.

Rule No. 4. The dead often leave you a map.

I don’t want to make it sound clear, or formal. The map might be helter skelter. It might be burned on the edges or contain symbols you have never seen.

Barbara and Adam built a model of their little town. It lived in the attic. A large wooden board sitting on two-sawhorses with the red covered bridge where they died and the house they love, painted white like a church, surrounded by small rolling hills made of tiny patches of Astroturf. They even added electricity so they could watch the tiny lights burn in the windows for eternity, or for however long they haunt their house. The town model is where Betelgeuse first appears after the Maitland’s summon him. Yes, the movie title is Beetlejuice, because it sounded cool and was easier to say—but his calling card, and the flashing neon sign in the graveyard, show he is named for the supergiant star in the Orion constellation associated with Osiris, the Egyptian God of the Underworld. The Maitlands don’t know that once they summon him, there’s no going back. Betelgeuse is shown banging around in the cemetery, spitting and reeling and humping, promising to scare the Deetz family out of their house. He is chaotic, perverted, hard to contain, and motivated by a wide variety of his own needs, including an improved eternal existence. He reminds me of some of the guys I used to date, and I wonder if I haven’t always been attracted to someone a little desperate to escape their circumstances. Or at least I can relate to it.

This map is their slice of the universe distilled down for Barbara and Adam to tend and admire. After Simon died, I made a map of the neighborhood he lived in, with all the places he loved. Each spot chosen based on his affinity and proximity to the place, or the place’s impression on him. The map looks like him, a decade of him, the decade he lived in the city. On my map, there are tall cottonwoods from the Ohio River where he grew up, there is a tiny replica of the Ideal Diner where we would eat breakfast hungover from late nights in small dive bars. There is a poorly drawn pool table with an eight-ball sitting in front of a corner pocket, a scene we replicated night after night over cheap pitchers of PBR with the older-times from the neighborhood who also didn’t have a reason to be home late on a Monday night. In the center of the map, I have drawn the entirety of Loring Park— the gardens, the pond, the bridge, the fountain and playground, the cathedral in the distance—and when I look at my little map, I can see him pushing our son on the swing sets.

The empty streets of my map are white. There are no buses, no exhaust, no cars, no people. I wonder if I should draw them in. If there should be more dirt, and curbsides, and littered plastic bottles. I wonder if there should be stop lights and crosswalks and coffee shops. I wonder if I can make the grass grow, or the cattails sway along the edge of the pond. I wonder if his Village Video, a place that closed years ago, could come back to life on the page before me. There is the eerie feeling holding this map that I could walk in this world on the page and disappear, and that he might be there—or here—then or now.

Over the years, I’ve found I am most interested in the maps left behind that send someone out searching to find the parts of the dead they didn’t know about. More like treasure maps. In my grandparent’s things, I found so many letters between them and their children. Biographies written by my great-aunt that explain how a marriage wasn’t perfect, or a career as pristine as it looked. I was often most surprised by candid letters that perhaps weren’t meant to be saved—ones where grandma admits she doesn’t like someone’s fiancé. But these things tell stories. I have a floral-patterned tea set from my Aunt Mary that she brought to my mother years ago, and when I look at it, I see her picking it out in an antique shop in Scotland, and I can smell the cigarette smoke from the shopkeeper and hear the taxis in the street behind her.

From Simon, there is so little. He was a minimalist at heart, who also struggled with alcoholism and stable housing. But I have his work jacket which he wore at the shop and his glasses and the portable thermometer he kept in his pocket. I have the spice jars he gave me—all the glasses lined up but empty, waiting to be filled again. There are things we do not part with, little things we keep just for ourselves, or so someone can discover us when we’re gone, placing pins on a map, each of us a cartographer for our dead.

Rule No. 5. In case of emergency, draw a door and knock three times.

When Barbara and Adam realize they can’t easily scare the Deetz family away—and keep their house all to themselves—they follow the book’s instructions for an emergency, then wait with the millions of other lost souls looking for answers. In Tim Burton’s beloved movie world, the afterlife appears to be a bureaucratic nightmare. Or perhaps this is just a larger commentary on the human condition—we sit around and wait for answers that never come. And maybe a comment on the seemingly endless mundane tasks we must do when someone we love passes away. Have you ever tried to transfer a car title? File a probate? Figure out a cemetery plot? Perhaps Tim Burton was nodding to the grief-filled days that often seem to be spent standing in lines.

When Simon died, I knew on a practical level that the emergency had ended. His last weeks had been chaotic, and I felt that there should have been some peace now that he was gone. But a panic was still surrounding me. I missed him so much and feared the empty spaces he left as a father. I realized that sometimes you miss your dead so much it feels like an emergency. You draw a door and knock three times looking for them—pulling their face from your memory when you long for them. Asking for help when you need it most. And sometimes they find you, and you spend the whole day wondering why they showed up, what it was they wanted you to know.

I have looked for my dead in the living over and over, and probably always will.

I know I told you the first rule is that ghosts inhabit the place they lived, but I’m not so sure it’s true anymore. After Simon died, I really started to think the dead can haunt their living anywhere. Maybe I was just drawing doors and knocking whenever I felt that tug of loneliness, whenever the emergency of his absence would creep in. Once, I swore I saw Simon leaning up against the blonde bricks of a building in Austin, Texas. I was only there for one day, just passing through. But there he was in the afternoon sun, head down, chin buried in his chest, feet crossed. I don’t know if he was ever actually in Austin, Texas, but my memory of him there that day, the ghost of him, or a man who looked like him, is one I recall regularly. I have followed other men around corners, and I have stared too long across the bar. I have seen men with knuckles like his, forearms like his, a twinkle in their eyes just like his. I have been absolutely sure I heard his voice down a hallway. I have looked for my dead in the living over and over, and probably always will.

Rule No. 6. It is not uncommon to think, I don’t know how I will get through this life without you.

When Lydia thinks she has lost Barbara and Adam to the underworld, she plans to jump from the same bridge they accidentally drove off.

When you tell your dead that you wish you could go with them—to the attic, to the other side— they will tell you “no.”

No, no, no.

This is where I felt the closest to Lydia. She is already grieving—she can’t stand to lose the Maitlands too. I can’t stand for her to lose them either.

Barbara and Adam promise they won’t leave her and beg her to stay alive. This is what I wanted too, for my dead to promise to haunt my house forever. To always feel them near. In the years after Simon’s death, there were moments that I wanted the closeness I had right after he was gone. As wildly painful as that period was, it felt like he consumed the air around me, every conversation, each night in my dreams. Ten years after his death, he feels further away. I miss that closeness sometimes.

Because getting through this life without him felt awful at first. It made me feel like a kid again. There is something about the alienation of youth. The work we do to ourselves, dressed in all black—black hair, dark eyeliner, boots in the summer, lips pursed. Maybe it was just that I grew up in the 90s, but I really got it when Lydia famously announces: “My life is one big dark room.” At one point in the movie Barbara says to Lydia, “You look like a normal little girl to me.” This moment kills me every time. Barbara sees past Lydia’s grief, her performance, her othering veil and sadness and isolation and says: you are not a bother, you don’t complain too much, your sadness cannot scare me away. I don’t know exactly when that alienation ends, but for me, it was when I found people who could really see me—and my hauntings. Often it was new friends, sometimes other lost souls that made me feel dreamy and excited about life, or in love with myself again, or for the first time. Or when the possibilities of something like love came close to me, the possibility of a companion who wanted to be by my side.

This is how I used to feel when I got a pool ball in the pocket: anything is possible. This is how I felt when Simon was standing next to me smiling with the pool que in his hand: less alone.

Rule No. 7. A séance is for the living.

In Beetlejuice, after the Handbook falls into the hands of Delia’s sidekick, Otho, he uses it to host a séance. His plan is to produce the dead for the living, or more precisely to a group of people at dinner party they wanted to make a business deal with, something like “Come see our real haunted house!” But what Otho doesn’t know is that his séance summons death for the dead. The ceremony starts to turn the Maitlands into corpses who will decompose rapidly, then crumble and disappear. To save them, Lydia summons Betelgeuse and asks for his help in exchange for her hand in marriage. In a rather action-packed sequence where death and a fate worse than death—being married to Betelgeuse—are all on the line for everyone in the room, the Maitlands survive and save Lydia. For me, Lydia is the ultimate antihero for grieving children everywhere, the ignored and easily dismissed, the troubled, the “they will outgrow it” kids. Her resilience and willingness to risk it all so that she can keep Barbara and Adam with her is the embodiment of the grieving mind’s desire to keep their dead close.

Sometimes a séance is how you commune with the dead, and sometimes it is how you remake them. I learned this early, sitting around the dining room table, when the grown-ups told stories about my aunt or my Grandpa after they died. We’ve all done it, after the funeral, when we are finally back together for the holidays. The memories live in these incantations, and their alterations, and their repetitions. It is in those moments you might hear a song you had forgotten the words to, see the lights flicker, see everything new and alive and otherworldly. Other times, these are the dinners where you begin to crumble—the loss finally settling in.

After Simon’s funeral, it felt like the stories told about him are of twenty different men. He was bold and shy, loud and quiet—quick with a story, sullen at times. Maybe we are all much more complicated than I care to admit. I heard stories he’d never told me. This is the séance, the making and remaking by people who knew him in different ways, at different ages, in different worlds. This is the raising of the dead in the church basement, at the Am-Vets Hall, in grandma’s backyard, buns placed on Styrofoam plates on the faux-wood folding table, while a chorus of voices bring the dead back to the room.

Eventually, I learn a séance can happen anywhere. You can conjure people in all sorts of places. When I step on the streets Simon walked a thousand times, I feel like his footprints are visible on the sidewalk, like I’m walking in his steps. I inhabit his swagger. My tennis shoes weaving a little, just like his black boots. I smell his lit cigarette ahead of me. I hear his voice on 15th street. I see him paused waiting under the streetlight, a little lit up from the 19 Bar, a little giddy from winning at pool, his Carharts pony-colored, the same as his hair.

Rule No. 8. There isn’t a guide for any of this.

In one of the final scenes, Lydia’s father Charles is sitting in his office reading. He announces in bewilderment, as he turns the book upside-down: “This thing reads like stereo instructions.” Most people assume he is still reading The Handbook for the Living and the Dead, but this is a new book— The Living and the Dead: Harmonious Lifestyles and Peaceful Coexistence. Unlike The Handbook, it isn’t a guide to the afterlife, it’s a guide to finding a way to make peace with your ghosts, and to living while holding onto the dead. It’s a task that can feel confusing and difficult to navigate, but the ending of Beetlejuice shows it can be done: the Maitlands and the Deetzes all live together. The home has Adam’s old office furniture next to Delia’s post-modern sculptures and new wave couches. Peaceful coexistence. The living and the dead.

Stereo instructions sometimes feel like the only way to describe it. At first you can’t find the volume and it is much too loud. The display blinks angrily at you, until you have pushed enough buttons to finally get the radio going. You can never tell the input from the output. The interference comes at the worst moments—in the middle of a meeting, when you are trying to get the kids out the door to school—piercing, often in the form of memories you weren’t prepared to revisit, your past, your ghosts. The way Simon looked the last time I saw him is occasionally projected onto the wall in front of me—while toddler shoes fill my hands and small feet are waiting to be squished into them.

Tim Burton’s vision is simple: the veil is thin. The two worlds are really one, though your transportation between them is limited. But the ending to the movie is one that embraces the challenge of navigating the here and the after. Perhaps in a small way, the film’s ending was the first time I really believed there was something better down the road from the grief I felt so intensely. I used to wonder, was the end of Beetlejuice tied up too neatly? Was the hole in Lydia’s heart so easily filled? But then I remember it’s a movie, and I cling to that happy ending now and then and forever.

What I know: sometimes the world of the living looks like the world of the dead and reads like stereo instructions. Sometimes the hands on the cuckoo clock fly around and around and you could be exactly where you want to be, with all your living and all your dead surrounding you, watching the springs throw the black bird out wildly, making the bulbs burst into beautiful flowers. Sometimes you don’t feel lonely, and the music rises, and when you dance, you float, and you shake and shake and shake.

Read the original article here