We live in an era of precarious conflict: highly-fragmented, hyper-connected, the world both smaller and painfully far apart, in combat geographically, and with our own bodies, from rogue cells to drone wars.

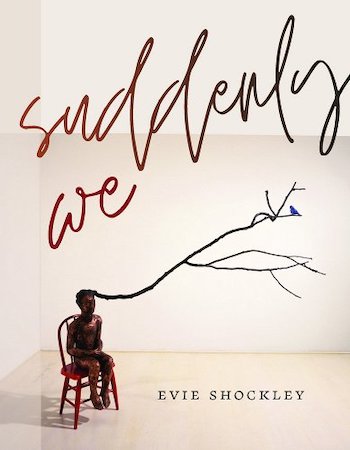

Evie Shockley’s suddenly we is a visually exciting, linguistically dynamic, and altogether thrilling shapeshifter of a collection that is both a response and antidote to these times. Beyond its experimental, polyphonic, modern architecture, at its core, it’s a nuanced and sensitive exploration of collective and individual identity, within the context of broader societal, historical and environmental obstacles.

Throughout the collection, there are multitudes and multiplicities, emphasizing the urgency of language now, and what it can and can’t encompass, yet the power of the collection is in the personal and intimate contemplations of voice, identity and agency. In “the lost track of time” she writes:

“i’ve measured out my life in package

deliveries and what’s in bloom. the time is now

thirteen boxes past peonies. if you can locate my

whenabouts on a calendar, come get me. i don’t

know where i’m going, but i need a ride.”

suddenly we offers readers that necessary ride, and this collection underscores why Shockley was recently named the winner of the Poetry Society of America’s 2023 Shelley Memorial Award which “recognizes poetic genius.” I spoke with Shockley over email about what it is to be human, and seek humanity in these in-between times, through verse and vision.

Mandana Chaffa: Might you talk about the genesis of these poems, a number of which speak to or engage with other creators? Who and what guided you through the process of interlacing them?

Evie Shockley: With the exception of the series of poems in “the beauties: third dimension,” each poem had its own genesis in one of the myriad occasions, ideas, and emotions that constitute the vast territory I (we) have traversed in the past six years. To even gesture towards it—the international #BlackLivesMatter protests following the murder of George Floyd, the multiple signs of US democracy’s frailty, the unfolding of the coronavirus pandemic, the increasing numbers of mass shootings, and the further evidence of climate change, along with all the sometimes encouraging and sometimes horrifying ways that people and institutions have responded to such events—is to remind myself of how difficult it often was finding the energy to write, let alone discovering the forms that could carry what my poems needed to carry.

MC: Many of these pieces point to forced societal roles that imprison the individual into a tight container, in poems that break through traditional forms, underscoring the friction of form and content.

From “can’t unsee”:

“a woman is innocent until proven

angry. a man is innocent until

he fits the profile. a child is

innocent until she sees her mother

or father in cuffs. can’t unsee…”

This idea of innocence, individually and collectively (and who gets to define that), is a thread that runs through the collection. There’s the personal aspect (and elsewhere you reframe the lost innocence of Eve gorgeously). And of course, the political power structures that commit harm and (mis)use language to their own ends, stealing one’s innocence, one’s individual Eden.

Language is both tool and terrain in this racialized ‘loss’ (theft) of innocence.

ES: Indeed. Others more eloquent than I am have talked about the seemingly instinctive need of the powerful to grasp the garment of innocence and wrap it around them like a shield. The US could not simply be the victim of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center; it had to be an innocent victim, as though it had played no role in creating the conditions that made its financial epicenter a target. Or, for an example that I take up explicitly in the book, the US government and many of this country’s people seemed desperate to locate the blame for the pandemic on people or causes that were outside our national boundaries or that, if within the US, could be othered, alien-ated, as the spike in anti-Asian violence made manifest. By the same token, innocence is denied—rhetorically, ideologically—to the disempowered, as I highlight in the lines you quoted. When activists or scholars call attention to the criminalization of Blackness and Black people in the US (and many other places), they are pointing to the way we are denied the presumption of innocence, time and again, in the courts and in the court of public opinion. Language is both tool and terrain in this racialized “loss” (theft) of innocence.

MC: Similarly, I feel so much hope in this collection’s embrace of the “we.” Many works of literature are first or second-person narratives, but we, that is of the populace, of the movement, of a forward motion: we the people, we will get to the promised land, we are the world. Of course, the other side of that “we” is we the mob, we the unquestioning masses, but there’s a deep sense of connection in many of these poems. So much motion: evolving, or turning, throughout the collection. From the poem “perched”:

“…i poise

in copper-colored tension, intent on

manifesting my soul in the discouraging world.

i am

black and becoming.”

ES: One of my main interests in the book is how our understanding of ourselves as individuals interacts with, informs, limits, or opens up the ways we imagine ourselves in relation to others—groups of others. The poem “perched” is an important one for signaling this interest, if quietly, in ways that are suggestive for lots of other poems in the book. Like so many poems in the African American tradition, it uses what some have called “the i that means we,” which allows an individual experience to stand in for a widely shared or generic Black experience. The poem is ekphrastic, thus its i is plural in a more specific sense: it is the young girl figured in the sculpture, “Blue Bird”; it is something I imagine or sense in the experience or emotional repertoire of the sculptor, Alison Saar; and it’s some aspect of myself.

Moreover, the sculpture itself, which appears on the book cover, seems at first to be of a single figure but includes as well the blue bird that gives the piece its name. What kinds of connection between the girl and the bird does the sculpture enable us to envision? The poem suggests one or two of many. Other points of possible connection are animated, I hope, by the invocation of the “world” in which this i (these i’s, we) must “become.” What the book makes a space for thinking about are all the things that play a role in shaping who an individual may see herself in community with or in solidarity with: the tiny personal or large historical events, the emotional openings or obstructions, the largely random or carefully cultivated interpersonal encounters, and so forth. The title is partly tongue-in-cheek, in that only rarely does one’s sense of collective belonging or connection with others happen “suddenly.” The major social formations (divisions) we are living with today—racial, national, religious, economic, regional, etc.—have been building / being built for a long time. In many of these poems I’m wondering, pondering, how we can make our actions today the pre-history of new or different forms of collectivity.

MC: There are so many layers in the collection, including lush poems like “fruitful,” in which “you grow my garden no you are / the whole of it” followed by a verdant list of nature’s glory in which “here, i become my best self, i exist / at peace with birds and bees, no knowledge / is denied me”. This poem is followed by “dive in” which is an equally sumptuous engagement with desire and intimacy.

Both in terms of content and craft, how did such a range of poems come about? Do you find yourself writing in sections, as it were? Or is the personal and political so entwined in your aesthetic that you’re writing about a range of themes, multiple styles, all the time?

And perhaps more philosophically, how do we embrace our personal selves and desires, with the political demands of being a human being at this time? How does the heightened awareness and immediacy of reactions co-exist with the being of human being, which runs on a completely different temporality?

One of my main interests in the book is how our understanding of ourselves as individuals interacts with the ways we imagine ourselves in relation to others.

ES: One thing your question suggests to me, regarding range and stylistic variety, is that this is the flip side of the “unruliness” or “uncategorizable-ness”. That is, the heterogeneity I used to fear was a failing—or used to fear would be seen as a flaw—in my work, might actually be one of its strengths. Because I write poems, not books of poetry, I don’t approach the page with any sense that what I write today must be “like” what I wrote yesterday. I try to avoid my default modes and attune myself closely to what the ideas, language, or feelings giving rise to a poem seem to want to become. The decision about what poems speak to each other enough to co-exist generatively in a collection comes later. But I’m always pushing myself to think about my experiences as holistically as possible. The tools I’ve amassed as a literary scholar steeped in Black feminist thought, the Black radical tradition, and oppositional poetics, among other analytical approaches—prepare me to bring critical, intersectional, associative thinking to my daily life, as well as to the structures and language I use in writing poems. Unfortunately, that doesn’t mean I’ve figured out how to balance or reconcile all the demands of my being (as a person with insistent bodily needs and messy, complex emotional desires) with all my political commitments. Rather than attempting to offer sage advice or one-size-fits-all pronouncements, I’ll just say I try to keep my wits and my tools about me, and use them in making the most ethical choices I can in the moment. Half of the battle is recognizing when such a choice is before me.

MC: The collection starts with the visual and verbal vista of “alma’s arkestral vision (or, farther out)”: the “we” that is created by multiple “you”s and the lone, but necessary “me” that closes the link and makes it complete. It ends with the remarkable poem “les milles” which I’ve already referred to, which starts with this indented couplet, and ends with the one that I’ve posted right below it:

“there is no poem unless i

we can find the courage to speak[…]

there is no poem unless you

we can find the courage to hear.”

What’s in the middle is a moving, painful contemplation about how we find it hard to move on from history, or learn from it, “map the territory of the human, / with arrows pointing in every / direction : some leading from / you, some leading to you.”

I’m especially taken with the bookends of the first and last poems of the collection (as well as the central passages within the last poem). We live in a time that calls for great courage, though perhaps it always takes immense courage to maintain one’s humanity. I keep returning to how you entwine the lowercase and capital P of politics (and person); it feels deeply connected to many of the poetic voices of the ’60s and ’70s, yet is entirely of the moment, as you ask: “must every place-name on earth / be a shorthand for violence / on a map of grief”?

ES: Perhaps the reason the political and the personal are always intertwined in my poems is because I gain and hone my politics in community: through exchanging ideas, reading others’ arguments, learning about experiences that inform people’s commitments and critiques. I also fuel my motivation in community; insofar as I know nothing I do alone is going to create change of the magnitude needed, it’s (inter)actions with like-minded/open-minded people that inspire me to keep working to envision and engender a world that is fundamentally just and nurturing for all life (not only some humans, not only humans). Collectivities that we’ve had thrust upon us but have reshaped to serve simultaneously as our spaces of refuge, in the context of this money-driven, power-hungry world, will have to be exchanged for the collectivity that our shared planetary existence constitutes. But how on earth (pun intended!) do we get from here to there? On what terms can we forge the new solidarities that will make relinquishing our current racial, gendered, ethnic, national, class-based, religious, species-based forms of belonging (and division) even thinkable? suddenly we begins with the dream and ends with the current reality. That may seem counterintuitive or even pessimistic, but it’s not intended to be. Like good poems so often do, I hope readers will find that the book’s ending propels them back to the beginning, to re-read “alma’s arkestral vision” with a fuller sense of its stakes and a readiness to work towards the greater collectivity it imagines.