Dark matter has a warming effect on exoplanets that could be observed – according to astronomers Rebecca Leane at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Juri Smirnov at Ohio State University. The duo has calculated that the heating occurs as dark matter particles collide with exoplanets, depositing energy as they scatter and annihilate. The astronomers say that his heating could be easily and extensively explored in the coming years, as the number of known exoplanets – planets orbiting stars other than the Sun – continues to expand.

Observations of galaxies and larger astronomical structures suggest that the universe contains a vast amount of dark matter particles, which interact via gravity but not electromagnetically. However, the detection of dark matter particles at shorter length scales has remained elusive. In their study, Lane and Smirnov suggest that the effects of dark matter could be observed on the planetary scale.

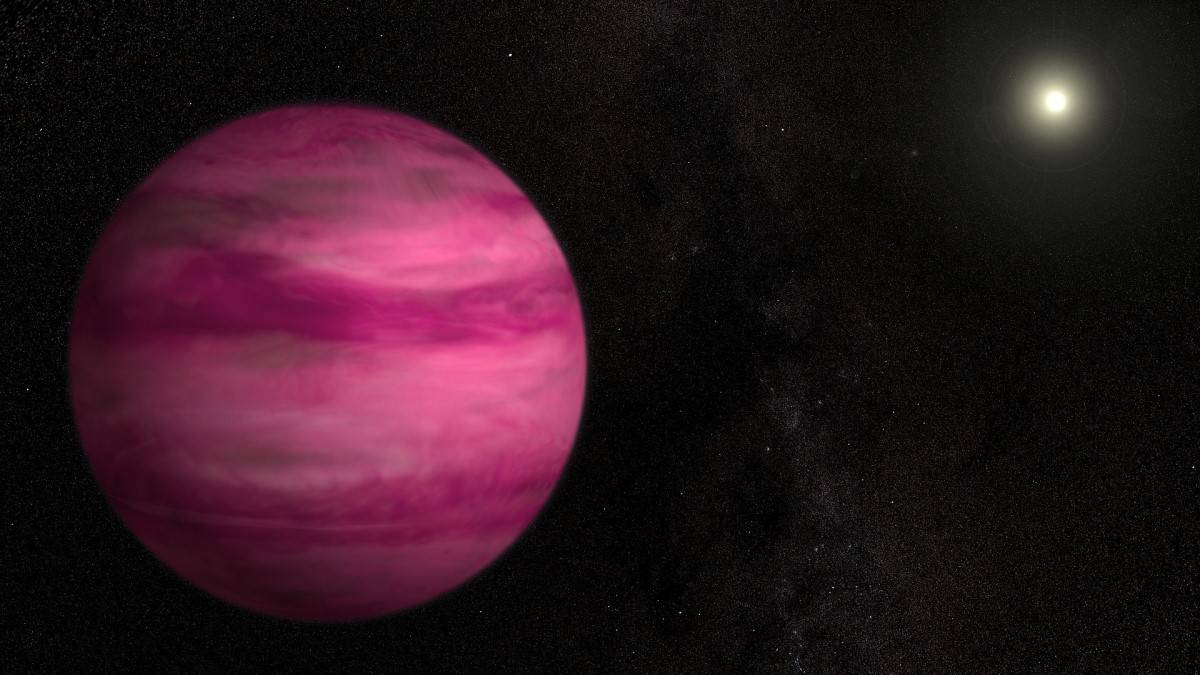

The duo reckons that dark matter particles captured by the gravitational fields of an exoplanet will scatter and eventually annihilate within the mass of the exoplanet. This will heat up the exoplanet, causing it to emit more infrared radiation than would be expected due to heating by its host star.

Radial test

Observations of the Milky Way’s rotation suggest that the density of dark matter in our galaxy increases towards its centre. This means that the dark-matter heating model could be tested by looking for a relationship between planetary temperature and radial position within the galaxy. If Lane and Smirnov’s predictions are correct, exoplanets should be warmer the closer they are to the galactic centre.

Although this effect should also be seen in the temperature of stars, there is a key advantage to using exoplanets as dark matter sensors: they do not produce their own heat so any anomalous heating would be far more noticeable.

Cosmic-ray detector might have spotted nuggets of dark matter

Particularly promising candidates for study are Jupiter-sized gas giants and brown dwarfs – the latter being 10 or more times massive than Jupiter, but not massive enough to be stars. Even better would be hypothetical “rogue planets”, which are predicted to have escaped from their star systems and now wander unheated through interstellar space.

The duo points out that exoplanets are ideal candidates for a dark-matter search because there are so many of them. More than 4300 have been discovered so far, and many more should be identified by upcoming observatories such as the European Space Agency’s Gaia space telescope.

The research is described in Physical Review Letters.