If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

On July 1, 2020, in the middle of worldwide lockdown, fans of up-and-coming indie rock band The Runners were posting selfies of outfits they were wearing to a maskless, non-socially distanced live concert happening that night in New York. At the encore, lead singer Eddie Kaspbrak confirmed yearlong speculation of his romantic involvement with a fan, Richie Tozier: he announced that the next song would be a tribute to Tozier, closing with “I love you. Happy to do it.”

This concert didn’t actually happen. And the band doesn’t actually exist. But everything else—including the fact that “HAPPY TO DO IT” was the 16th trending US topic for a few hours on Twitter—was very much real.

This all happened in updates 358-382 of The Runners AU by @richietozxer, a work of fanfiction based on Stephen King’s It. Fanfiction is a thriving genre; the popular fanfic clearinghouse Archive of Our Own lists more than 14,000 related stories. What sets The Runners AU apart from other fan-created works, however, is that it’s told entirely through phone screenshots. On Twitter.

What are SMAUs?

Twitter is no stranger to literary experimentation. The broad category of Twitterature covers various explorations of its capacities as a text-limited, collaborative medium—from Twovels to haiku bots to shitposts that gain an aphoristic patina as they transcend Weird Twitter to become mainstream PSAs. But one particular form especially pushes Twitter’s boundaries and limits as a multimedia storytelling platform, both in how stories are told and how they’re consumed—namely, the Social Media AU.

AU is a fanfiction term for an “alternate universe” story, one that changes the genre or fundamentals of its source material. AUs transpose existing characters into contexts and genres that are often completely divorced from the source material (or “canon”)—new settings range from academia and philharmonic orchestras to spy heists and outer space. Alternatively, some SMAUs extend the source material beyond its official ending to “fix” or examine unaddressed parts of the world. Familiar characters serve as conduits to explore and develop canonical relationships and themes through new angles.

Social Media AUs are composed entirely of text messages, social media posts, and other audiovisual components presented as image-based threads on Twitter.

Social Media AUs are works of multimedia fanfiction composed entirely of text messages, social media posts, mock news articles and websites, audio bytes, video clips, and other audiovisual components presented as extensive image-based threads on Twitter. The form first gained mainstream media attention through Outcast, a horror SMAU about K-pop band BTS by Twitter user @flirtaus that amassed over 500,000 followers and went viral for the duration of its six-day run in January 2018. Nightly polls gave readers the opportunity to direct the storyline in a choose-your-own-adventure style that Billboard called “Twitch for fan fiction.”

Since then, SMAUs have particularly taken off in the fandom surrounding Andy Muschietti’s September 2019 film adaptation of Stephen King’s It: Chapter Two, with over 470 complete and in-process works and counting. One of the earliest SMAUs in the fandom, an acting AU called Turtle Creek, by @rorschachisgay, has over 3,400 followers.

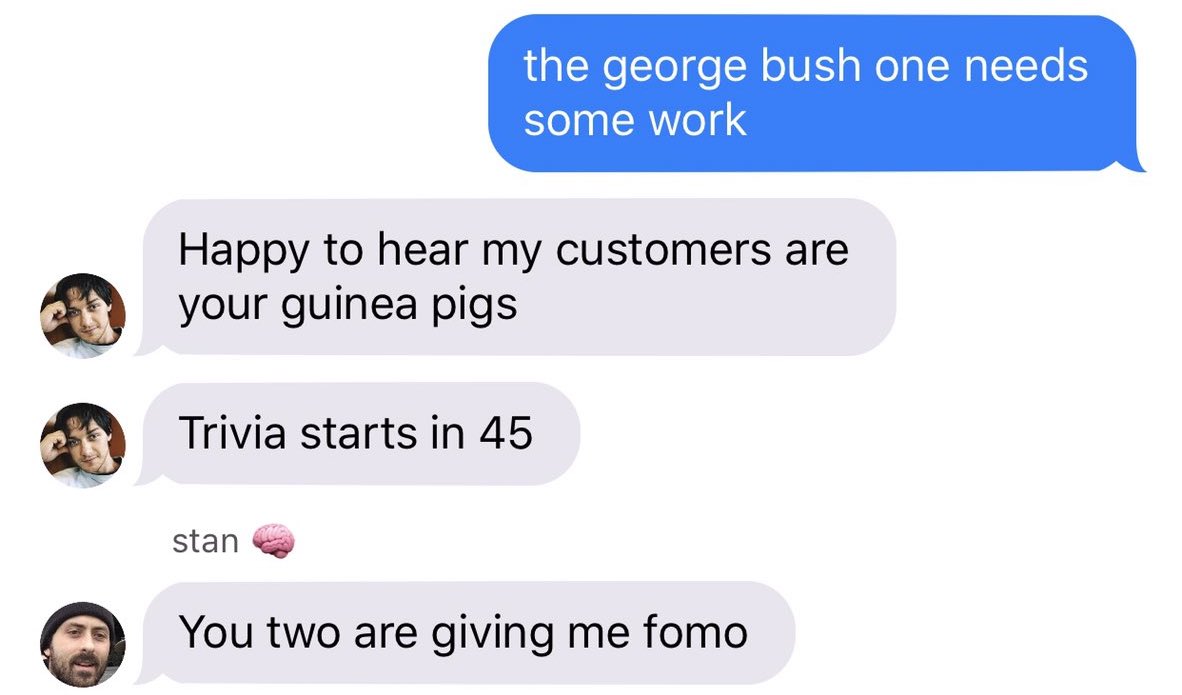

SMAUs are organized in nested threads reminiscent of a DVD menu—each tweet in the top thread can be expanded for chapter selection, behind the scenes, bonus content, and playlists. The narrative challenge of conveying plot primarily through text message and digital ephemera lends itself to experimentation—differing texting styles imply voice and personality; innumerable group chat and DM permutations build tension by constantly alternating perspective; bystanders step in to live tweet when characters are forced to put down their phones.

SMAUs feel much like looking at a stranger’s phone over their shoulder—and this voyeuristic quality reflects how we connect with others.

In many respects, reading SMAUs feel much like looking at a stranger’s phone over their shoulder—and this voyeuristic quality reflects how we connect with others in a hyperconnected world. The significance of the minute behaviors of online life we take for granted are given full consideration when we’re invited to witness events as bystanders (or amateur NSA agents)—there’s an assumed subconscious truth in the text messages we delete before sending, the thought patterns traced by our Google search histories, the pictures we don’t share on our camera roll. In the things we don’t say out loud and the things we are too afraid to ask for. Though we are not granted the confessional quality of first-person narratives or the physical immediacy of film, we are granted a glimpse into something much more private—intimacy and distance held in tenuous harmony.

Why Twitter?

Using social media as a medium for storytelling isn’t new—Lauren Myracle’s The Internet Girls series of the early aughts, written entirely in IM’s, is an early example of how cohesive narratives can be conveyed and enriched through short text messages. Subsequent works like Emmy Award winning web series The Lizzy Bennet Diaries and TV series SKAM, go one step further by integrating the story itself into social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter, featuring “real-time” updates through character accounts.

But what sets today’s SMAUs apart are the creative communities they organically form. Unlike traditional forms of media that are largely produced and consumed as isolated bodies of work, SMAUs are built much like an exquisite corpse—a patchwork of fanart and mock trailers commissioned and gifted, images and edits borrowed from crowdsourced repositories, plot updates handed off between collaborating authors and driven by reader polls and feedback. Housed in a ready-made open forum, engagement becomes inherently communal—quote retweets, tags, and anonymous Q&A through CuriousCat build a web of threads that provide a simulation of live discussion. With cameo appearances of mutuals and characters from other SMAUs, each work becomes part of an ever expanding multiverse that exists in a microcosm both separate from and embedded in the other realms of content that Twitter cultivates.

Why It, and why now?

Part of the reason for the ongoing fervor surrounding Muschietti’s It: Chapter 2 is that it falls prey to the bury your gays trope—the tendency for LGBTQ characters, especially queer women, to be disproportionately killed off or otherwise meet unhappy endings in mainstream media. And for a community in which any form of positive, nuanced representation is yet a recent novelty, each death hits particularly hard.

It: Chapter Two begins with the death of Adrian Mellon, a gay man based on the real-life victim of a hate crime, and ends one of the main characters, Richie Tozier, a closeted gay man whose internalized homophobia was exploited by the titular monster, mourning the death of his queer-coded love interest. In spite of the story’s overarching themes of trauma resolution and the value of found family, Richie obtains neither satisfying closure nor implied growth—he doesn’t even get to say that he’s gay out loud. We witness the trauma, but not the healing.

This is the mantle that the It fandom has picked up—the vast majority of fan-created works center on “fixing” the narrative surrounding Richie, offering him the opportunity not only to come to terms with his sexuality, but also to live as his authentic self with the one he loves. Feelings of loss and dissatisfaction often drive fans to create alternate universes in which lives on the margins are taken out of the footnotes and given the full complexity they are due.

But the other reason why SMAUs have taken off is timing—on the cusp of a pandemic, worldwide social upheaval, and an onslaught of natural disasters, the It fandom on Twitter has served not only as a space for much-needed distraction but also as a source of camaraderie and support.

SMAUs are an embodiment of how social media platforms can be wielded to cultivate prosocial creation and consumption of art.

As Eddie Kaspbrak, lead singer of the eponymous band The Runners from @richietozxer’s SMAU, finalized the setlist for their highly anticipated concert, another universe saw increasing restrictions as daily COVID cases and deaths broke records with unstinting regularity. Much of reality had shrunk to a few rooms and screens displaying an endless panorama of bodies suffocating in hospital beds, blood and tear gas smothering the streets, ash falling from the sky. Those straddling these two worlds were able simply to open a new tab and climb through the window, gathering together in a dark venue in New York without leaving their rooms. Clothes that haven’t been worn since lockdown were taken out for selfies. Phones lit up excited faces as fans sent tweets to their friends with theories on how the climax of this story brewing for the past three months will unfold. And as the concert went underway, as “HAPPY TO DO IT” populated enough tweets to amount to a collective scream of delight, these fans were no longer isolated bystanders witnessing from afar. For a period of time, they were active participants in an event that brought them together in a shared space of their own creation—a place where as many permutations of happily-ever-after’s can exist as real-life horror movie tragedies.

SMAUs are an embodiment of how social media could not only be the next frontier of collaborative multimedia storytelling, but also how platforms can be wielded to cultivate prosocial creation and consumption of art. It’s a grassroots creative coalition funded by Ko-Fi donation links and an earnest desire to create a world that we wish to see—one that is more diverse, that is not limited by traditional definitions of relationality or intimacy. One that grants depth and the possibility of a happy ending to those relegated to the sidelines. One where the lines between art, artist, and audience are consciously and consensually blurred—where reality on both sides of the screen are given equal weight.