Over the past fifteen years, I’ve had the pleasure of crossing paths with the peripatetic Angolan author José Eduardo Agualusa on several occasions. In 2008 we were in conversation at the Brooklyn Book Festival—my first as a moderator—to celebrate the release of his novel The Book of Chameleons, which won the Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. Eight years later, at an event at Community Bookstore in Brooklyn, we met again to talk about A General Theory of Oblivion, winner of the International Dublin Literary Award and shortlisted for the Man Booker International Prize.

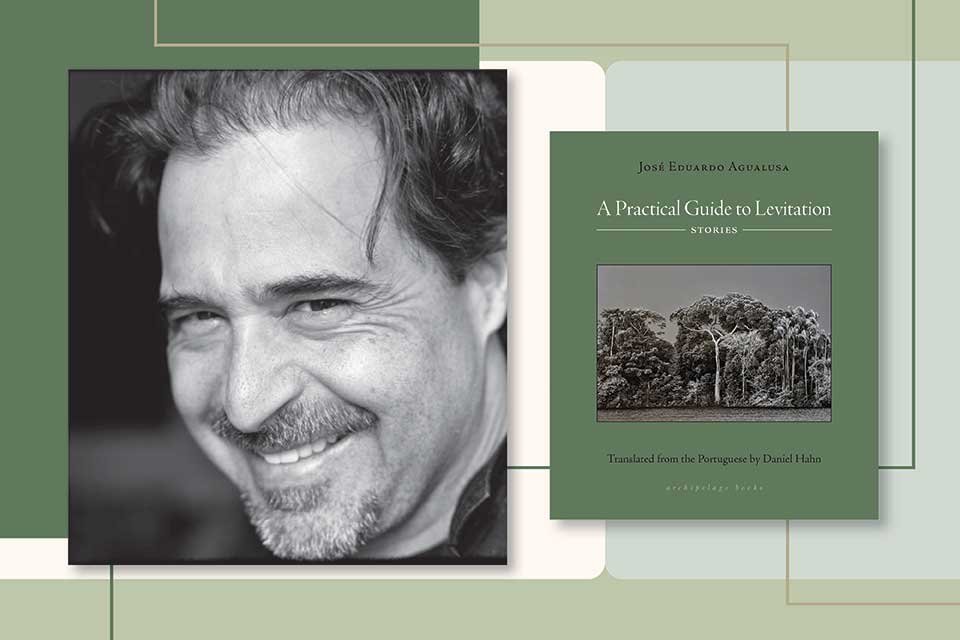

This month, Agualusa will publish a new collection of stories, A Practical Guide to Levitation. Like his last two books, it is published by Archipelago Books; and like all his English-language works, it is translated by Daniel Hahn. What a joy, for me, to reencounter Agualusa’s fictional universe—a world of talking lizards and enchanted trees, exiles and eccentrics—and, even more, to reconnect over email with the writer himself. We spoke of Borges, baobabs, truth and fabulation, among other things.

Anderson Tepper: José Eduardo, so good to be in touch again after a long time. How are you and where are you? How have you coped with the difficult past couple years of the pandemic and all else?

José Eduardo Agualusa: These last years, I’ve been spending more time on Ilha de Moçambique, a small and very old historical town, in northern Mozambique. The last month of May, however, I spent in Angola, traveling around the country. I was in the south, in the Namib desert, following the filming of Os Papéis do Inglês, a film by the Portuguese producer Paulo Branco based on three books by the Angolan writer Ruy Duarte de Carvalho, with my script. I was later in Luanda and in the central plateau, doing research and interviews for my next books, a biography, As vidas e as mortes de Abel Chivukuvuku, and a historical novel, O mestre dos batuques.

The two years of the pandemic weren’t so difficult for me. I spent the first six months in Lisbon, with my eldest son, Carlos, who is an actor, and then in Inhambane and Ilha de Moçambique with my wife, Yara, and our baby daughter, Kianda Ainur. I wrote, walked, and swam a lot. I watched whales. The Covid pandemic did not have a major impact either in Angola or Mozambique. So far, less than two thousand people died of Covid in Angola, and less than three thousand in Mozambique. Angola has thirty million inhabitants; Mozambique, too. In the same period, more than fifty thousand people died of malaria in Angola and Mozambique.

Tepper: Tell me about your new collection, A Practical Guide to Levitation. How did it come together, and what is the range in time of the different stories?

Agualusa: The book was organized by Daniel Hahn. He was the one who selected the stories. There are thirty texts, some very, very old, which I don’t even remember having written, and others written just a few months ago. The stories are not arranged in chronological order, which seems good to me. They travel through very diverse geographies and themes.

Tepper: What are some of the common themes or preoccupations that connect the stories, whether they are set in Brazil, Angola, or Portugal and in past or recent times?

Agualusa: These thirty stories contain many of my most persistent concerns. Some are of an existential nature, such as identity issues, and others more prosaic—such as fear of the police. A person knows he comes from a country that is not fully democratic when he is more afraid of the authorities than of petty criminals. There are also several stories that, in one way or another, refer to the long civil war that Angola went through.

Tepper: There are fascinating figures throughout—levitating people, ex-guerillas and exiles, even magical baobab trees. Tell me about these strange, bewitching spirits and what they suggest about Angola, in particular.

Agualusa: Many of those fascinating figures you refer to actually exist. They are real people. For example, Sérgio Guerra, who appears in the short story “The Tree That Swallowed Time,” is a friend of mine for many years who at a certain point, living in Luanda, began to “collect” baobabs, saving them from death. Angola has always seemed to me an extraordinary country for a writer to live in because it is possible to find a good story in every corner. This has to do, on one hand, with the extremely eventful history of the country. It also has to do with the prevalence in urban environments, even in the oldest ones like Luanda, of a certain African mythology—what you call “magical realism” but which is simply part of our reality.

Angola has always seemed to me an extraordinary country for a writer to live in because it is possible to find a good story in every corner.

Tepper: You also refer in the text to famous writers such as Borges, García Márquez, Pessoa, and Lispector, among others. How are these authors important touchstones for you?

Agualusa: A writer is first and foremost a great reader. In my case, I continue to keep the company of all the writers who formed me. They are part of my life, every day. I find it natural that they appear in my books. To write, every morning I start by reading excerpts from novels that I really like. Or else I read poetry. These passages, these verses, help me wake up to writing. It’s part of my process. I write by contamination.

I write by contamination.

Tepper: In the story “The Sentimental Education of Birds,” the narration alternates between the Angolan rebel leader Jonas Savimbi and a journalist-novelist who has written a book based on Savimbi. What did you want to explore in their different perspectives?

Agualusa: The truth doesn’t interest me. I think truth is a totalitarian concept, perhaps because I lived in Angola during the time of the single party. At that time there was one truth—the truth of the party—which could not be disputed. For me, as a writer, what interests me are the different versions of the same event. Jonas Savimbi was an extremely complex character, a man who put his greatest qualities—courage and intelligence—at the service of his worst defects. I’m fascinated by cruelty, by evilness, because I don’t understand it. I write to try to understand.

For me, as a writer, what interests me are the different versions of the same event.

Tepper: A Practical Guide to Levitation is translated by Daniel Hahn, whom you’ve worked with on all your English-language books. What is your relationship like with Daniel, and how has it developed over the years?

Agualusa: Daniel became a translator with my books. Before that he was already a writer. A good translator is also a good writer—has to be. Translating is a creative craft. It’s a re-creation. I was immensely lucky to have found Daniel. Thanks to him, I managed to have a voice in English that respects my world and my rhythm. Daniel makes my books so much better. More importantly, I made a friend who has been with me all these years, whom I admire a lot and trust completely.

Translating is a creative craft. It’s a re-creation.

Tepper: I’m very eager to read your most recent novel, The Living and the Rest, which won the 2021 Portuguese PEN Prize and will come out in English sometime soon in Daniel’s translation. What can I expect—how is it like or unlike your other books?

Agualusa: The Living and the Rest is a novel from the same family as The Book of Chameleons or The General Theory of Oblivion. For me, it’s the joy of pure fabulation. I wrote these books as if I were at home, telling stories to my friends. Making up the stories as I tell them. Watching the way the characters grow and weave the plots themselves.

Tepper: Finally, I remember when A General Theory of Oblivion won the 2017 Dublin Literary Award and you planned to help set up a library on Ilha de Moçambique with the prize money. Were you able to get that project off the ground?

Agualusa: Unfortunately not. It is not easy to buy a house on the island at a reasonable price that can be used to install a library. In recent years, however, house prices have dropped a little for the worst reasons: due to Islamic terrorism in northern Mozambique and the Covid pandemic, with the consequent collapse of tourism. So, thanks to this misfortune, I might be able to buy a good place now. I hope so.