Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

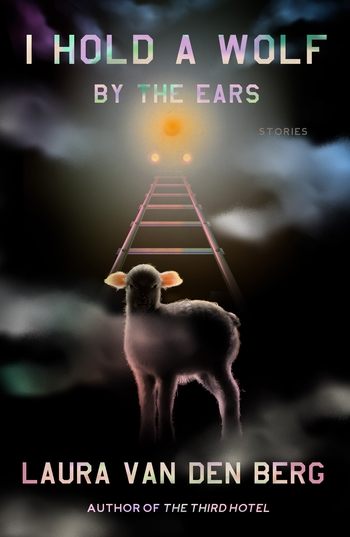

In Laura van den Berg’s collection I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, women are adrift in Florida, Iceland, Italy, in an unnamed medium-size American city, in their marriages, and in the depths of patriarchy. The collection’s title and its final story is the English rendition of the Latin, Auribus teneo lupum, which the van den Berg’s character translates as “there is no easy way out.” The characters of the collection, even the ones with overseas travel budgets, teeter on the edge of life itself.

Van den Berg narrates their troubles and their denials with fine elegance that obscures the dagger until it comes. In particular, the turns in “The Pitch,” a story of a couple in Florida and a mysterious missing brother in the woods, and “Karolina,” in which a woman runs into her ex-sister-in-law in Mexico City and what ensues is violence, past, present, direct, subtle, and stalker-y, unsettled me.

I spoke with van den Berg about dying and her 100-supplement-a-day grandmother, empire striking through the American tourist, the most Florida of Wolf’s stories, and the ultimate Karen of the collection.

JR Ramakrishnan: Almost all of the stories feature death or imminent death. I read that your father passed away recently. People’s awareness of death is very interesting—some people have it from having experienced it earlier and very intimately and others, maybe most, later in life. When did you start considering death?

Laura van den Berg: As a child, I was terribly fearful of people in my life dying. I never had a major loss with a young child so I don’t really know exactly where that came from. It’s interesting thinking about this now because I lived with my grandmother when I was a teenager and she was obsessed with not dying. She was convinced that she was going to live not forever, but to 120. She actually lived to be 101. She—and this is not an exaggeration—took 100 supplements a day. Even when she herself was in her 80s and 90s, she refused to spend time with other elderly people because she felt like age was contagious. She had pretty intense ideas about death and dying. She was at once terrified of dying but also in total denial about age and illness. I lived with her at such a formative time so I am sure it had some sort of impact.

JRR: There are a lot of Americans touring abroad in these stories. You have them in Italy, Iceland, and Mexico City. Your last novel was partly set in Havana. You guys have the advantage of empire and also wealth but at the same time, there’s this psychological and physical isolation, right? There’s also the expectation to be catered to. Your couple in Italy in “Cult of Mary” dislike the guide’s feminist politics and plan their TripAdvisor review. This concept of service seems 100% American to me. As someone who’s traveled much more than the average American, how do you see Americans abroad?

LVDB: I started thinking a lot about this during The Third Hotel, and especially with the obsession with authenticity, which is often a huge part of the marketing of American travel. I had never really read travel blogs before but I started to read them because that novel is so much about tourism and specifically, a massive influx of tourism in a really singular place at a very specific moment in time. So much of the narrative around Havana is about “the authentic human experience,” which, of course, just a fiction, a dream of capitalism, and the type of thing that can be packaged and marketed quickly.

I think part of the condition of the American abroad, and more specifically the white American abroad, is that we are coming from a place of empire. On the one hand, I think there is a profound desire to escape empire and be in a place that’s unfamiliar. Then there’s an equally strong impulse to recreate empire wherever you go. I think it means to be kind of caught in this duality of: I want to escape and have that, you know, “authentic” travel experience where I can see no traces of empire. And yet to be in that situation is actually so foreign and unfamiliar, it’s really destabilizing and then there’s the compulsion to actually create empire and be catered to in the ways you were speaking to before.

JRR: Who are your favorites of the Americans abroad genre?

LVDN: I read, particularly for The Third Hotel, and have continued to read a ton of travel literature to use a very broad category, but certainly, everything from Garth Greenwell What Belongs to You to Katie Kitamura’s A Separation to Graham Greene. It’s become a very capacious genre. It’s ultimately not up to me as to whether it was a successful project or not, but part of my ambition for The Third Hotel was to reimagine what the American abroad novel might look like and to reimagine what travel writing fiction can look like.

I am inspired by contemporary works of travel literature. It remains a fraught genre and it comes with a ton of baggage. I felt like I needed to sit with that baggage and think about it very carefully if I was going to attempt to do work in that space. It has been a huge area of interest to me. Although lately I’ve been orbiting back to writing about Florida, which of course is the place that I know in some senses.

JRR: I was wondering if you had read much of the opposite gaze, say someone from Beijing writing about Los Angeles? I don’t mean like an American immigrant narrative, but let’s say someone who’s maybe the Laura van den Berg of Iceland, maybe?

LVDB: I think Hernan Diaz’s In the Distance might be an example of what you’re talking about. It’s a kind of Western but written from a POV of an immigrant. I love that book. I’m interested in not just Americans, or even other people from other countries coming to America, but also in other places and travel literature more broadly.

JRR: What is the most Florida of these stories?

LVDB: Probably “Slumberland.” That story syncs with the landscape I see when I’m walking around now. A lot of the things and the places that my character photographs are right around my sister’s house and my neighborhood. I was actually staying with her when I started writing that story.

I aspired to write into those stories that very question of believing women and the consequences of not, but also the daily private ways that white women support patriarchal violence.

Then, “Lizards,” which came from me thinking of the boys I grew up with, who were basically misogynistic. I wondered what became of them, and what kind of conversations might they be having—or not—about Brett Kavanaugh with the women in their lives.

Another thing that happens here is lizards getting in your house, which really freaks me out. That feeling of nature, always wanting to come in, or trying to figure out ways to get around the barriers that humans have created, feels archetypically Florida to me.

JRR: In “Lizards,” and in “Karolina,” the question of women being believed (and not) in the context of gender violence looms.

LVDB: I aspired to write into those stories that very question of believing women and the consequences of not believing women, but also the daily private ways that white women support patriarchal violence, not necessarily in super visible public ways but consciously and unconsciously.

For the wife in “Lizards,” certainly her husband is doing horrific, unforgivable things to her. She is the victim but there is a part of her that really craves the obliteration and the kind of permission to look away and just sleep through it. She is caught in between this useless, superficial, anger and also the desire that says, can I just turn off the news and go to sleep? Questions such as: What would I be willing to change in my own life to dismantle the structures that make someone like Kavanaugh possible? What would I be willing to give up? I don’t think this character is prepared to engage in such questions. I also didn’t want to create a simplistic, victim-perpetrator dynamic. I wanted to pose something more complex and a little bit more nuanced. And then with “Karolina,” the protagonist of that story is unwilling or unable to reckon with violence in her own family and she shelters it to protect her brother. To my mind, that private choice has really powerful political implications behind it.

JRR: At the end of “Karolina,” the protagonist inflicts some violence of her own.

LVDB: Yes, for sure. There is this whole narrative that has been playing out with a friend off stage. She’s been fixated on wanting his time and his attention directed towards her that she’s missed the subtle ways he’s been trying to say, right now is really not a good time, I have other things going on in my life. That’s the reading intended of that story, that she becomes a kind of violent presence for them by appearing unbidden in the middle of the night, outside their home. She realizes far too late the dire situation that her friend’s been in but that she’s been willfully oblivious to.

JRR: I got to ask, because we’re in 2020, is this character the Karen of the collection?

LVDB: In terms of the Karen that you might see on the news, I would give the Karen award, dubious as it is, to the wife in “Lizards.” I don’t know how much self awareness she has, but in her defense, she’s being routinely drugged by a LaCroix-like portion, and that presumably cut down on one’s capacity for self awareness. In some ways, the protagonist in “Karolina” does act pretty Karen-like so perhaps they are neck-in-neck. I mean in my reading of her, there’s more self awareness, which I think in a lot of ways makes her actions more damning. There’s more cageyness, more secrecy, and more active manipulation. She probably is more adept at being able to read the room and shift her behavior as the social situations demand it. It might be more evil to do that, than perhaps the wife in “Lizards,” who is a little less self aware. But on the other hand, that runs counter to what I said earlier about the protagonist in “Karolina” being willfully oblivious to her friend’s situation. Yeah, I guess, it’s kind of a coin toss between them. Definitely two prospective Karens.

JRR: I see from Instagram that you are a pretty serious boxer.

Boxing reminded me so much of revising a sentence or a paragraph over and over and over again.

LVDB: There are many gradations of seriousness—I am at least semi-serious and I aspire to be super serious. I started by accident about two years ago. I rolled into the gym, thinking it was gonna be a cardio boxing class. Instead, it was a tactical boxing class and I didn’t know how to throw even like the most basic punches or do very basic footwork. The coach put me in a corner and I just stepped forwards and back and left and right for the full hour. On the one hand, it was so different than what I was expecting, tedious and frustrating, and on the other, I was totally enthralled.

It reminded me so much of revising a sentence or a paragraph over and over and over again. Boxing has some of that slightly obsessive resonance. I fell in swift love. I did work on all the basic stuff for a year and started sparring probably around this time last year. I would like to do an amateur fight at some point, probably a year from now. This wasn’t even part of my lexicon a couple of years ago and now it’s a huge part of my life.

JRR: There’s a long connection between boxing and writers. All men—Hemingway, Norman Mailer, etc.— except for you and Joyce Carol Oates (who didn’t put on gloves herself).

LVDB: Yes, she [Joyce Carol Oates] wrote about it [On Boxing]! Also Katherine Dunn boxed her whole adult life. She wrote as a journalist about boxing and boxed yourself and then collected her writings into One Ring Circus.

JRR: We talked about the violence in your stories. I started boxing myself in the last year, and I mean, we can talk about it as a sport but obviously, it’s combat.

LVDB: Yeah, certainly, if you are boxing competitively, it’s a very, very dangerous sport. The regulations have evolved over time—fights are shorter, rounds are shorter, fights are often stopped sooner. Still people get badly injured and even die. It’s appropriate, even if you love the sport to feel messy, complicated feelings about the physical risk factors people are exposing themselves to.

Even in my humble context, sparring can be rough. I have definitely gotten black eyes, bruises, and bloody noses. People often say you must feel fearless to spar and it’s actually quite the opposite, I get really nervous before sparring. I’m working through a space of really visceral fear. It’s actually something that keeps bringing me back to it is having the space to sit in your own fear and move through it. Over time, there’s something really powerful about that.

I’ve come to really love the rituals also. On the other side of the violence of a contact sport, there is this deep love, not always, but in my experience, there is often this deep camaraderie and respect that really can develop. You bond in a deep and unique way, right? This is not an activity that I’m doing with my friends; it’s a very specific relationship. It’s moving to me how often it’s the person who knocks you on your ass will be the same person who reaches down their hand and says, “Get up. Keep going!”

JRR: Although perhaps not in stylistic terms, but between boxing, Florida, Cuba, and writing about other places, it seems that you and Hemingway have quite a bit in common.

White people, we are a race. To write about whiteness is to write about race.

LVDB: I would say I hope that I write better! My most honest answer to that would be I have not read Hemingway in a really long time. I would have to probably need to revisit to have a more intelligent response. Hemingway had a very fascinating life but I do wonder to what extent, if at all, Hemingway thought about his own privilege, power, and empire and how that shaped his gaze. My sense is, based on the Hemingway I remember, probably not a lot. My enduring and ongoing ambition as an artist is to, not only be alert to those dimensions, but also to write into them and to think about how they have shaped my world.

JRR: White writers of the past like Hemingway would have not have had to consider some of the issues that white writers might (and do) consider in their writing now. I doubt he was giving too much thought to the kinds of things you thought about while writing these stories.

LVDB: Oh for sure. I would also imagine that the idea of writing about whiteness—that whiteness is a thing that you would think to write about—would have never ever occurred to them. I think that’s something that a lot, or at least I hope a lot of, white writers, are thinking about now. There’s a sense if you’re writing about race, it’s about writing characters of color or of communities of color. You know, white people, we are a race. To write about whiteness is to write about race. There was definitely not a lexicon that was on their radar then.