Find the perfect gift for the writer or reader in your life in our online store. Take 20% your entire order with the code STAYHOME2020, now through Christmas!

Bernardine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other depicts the complexities of identity through the interconnected stories of twelve Black British women, painting a portrait of the state of contemporary Britain that also examines the legacy of Britain’s colonial history in Africa and the Caribbean. Though Black women are not a monolith, there is something about the shared experience of a certain collection of people who identify together in gender-related experiences and the results of coming from places where colonialism—from the standpoint of the colonized and the colonizer—played an importance on how your skin color dictates how others treat you. For an African American woman who has read many British writers, reading Girl, Woman, Other was the first time I felt any affinity to such authors and their works.

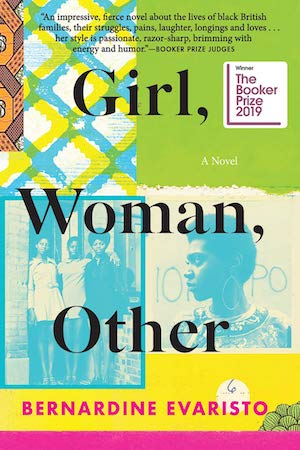

It was not surprising to me that this book won the 2019 Booker Prize. Although what was surprising is that Bernardine Evaristo is the first Black woman to receive the literary honor. Professor of Creative Writing at Brunel University London, Evaristo has written eight books that cross multiple genres and styles. Evident in Girl, Woman, Other is Evaristo’s willingness to play with style, voice, and lyricism. I spoke with Evaristo with an “American Black woman interviews British Black woman” kind of vibe. We spoke about Girl, Woman, Other with the context of understanding it from and for a Black American reader, the similarities and differences between American and British Blackness and Black womanhood, specifically, and the depiction of such in literature.

Tyrese L Coleman: I loved this book so much and found it hard to put down. When I told a white woman I met that I would be interviewing you, she said to me that she was surprised you won the Booker Prize but when I read Girl, Woman, Other, I knew exactly why you won the Booker Prize. I also read where a BBC anchor referred to you as “another author” when discussing the shared award with Margaret Atwood. Both incidents made me wonder whether or not you have noticed a racial and/or gender divide in the book’s criticism and, specifically, the reaction to you winning the award. If so, why do you think that is?

Bernardine Evaristo: I’m glad you enjoyed the novel so much. I’ve had very little feedback from individual American readers, mainly because the novel came out much later there. You don’t say whether the woman mentioned had read the novel or not—which makes a difference. People have opinions on the Booker Prize shortlists and winners without actually having read all the books. Or they’ve read one and decided that book is their favorite, without knowing anything about the competition. I’ve had incredibly positive responses from all kinds of readers to Girl, Woman, Other and since winning the Booker, the novel has gone out into the world to land in the laps of readers who wouldn’t usually read my work, even if they came across it. In the U.K. the main reading market is older and female, but since winning the prize my events have also been packed with men, often elderly men, some of whom have already read the book and loved it. I find this incredibly reassuring in the sense that they are responding to the humanity in my work and that they have encountered my twelve primarily Black British women and found them interesting and perhaps, even, relatable. We are all human beings, after all, with shared emotional drivers.

TLC: As an American who is slightly an anglophile (meaning, I watch a significant amount of British television and movies and am specifically obsessed with The Crown), Girl, Woman, Other felt familiar to me. Not because of what I think I know about what it means to be English, but rather what I know about what it means to be a Black woman. I was drawn to those moments of knowing that feel unique to Black womanhood, such as Carole’s constant respectability performance as she is surrounded by white people daily, especially white men, and her struggle to outperform just to remain equal.

I find myself and I see other Black women always saying, “we aren’t a monolith,” but we do have shared and relatable experiences. What were you hoping to say about the shared experience of Black women?

BE: As Black women in the U.K. and U.S., we will share certain experiences in that we are living in societies where we are racialized and where women are also discriminated against. My novel explores many women, one of whom is non-binary, from multiple perspectives, and this includes experiences of queer and straight sexuality, different classes, occupations, family set-ups, and cultural backgrounds, migration histories, rural and metropolitan women, and women of every generation through to a nonagenarian, and so on. My aim was to create as many stories as I could about Black British women and in so doing to counteract our invisibility in literature to present my characters as complex, flawed, and very real beings. All of these areas lattice across the text, so that while the novel is specific to individual narratives, there are so many points of connection for the reader, especially for Black women readers, and women of color more generally.

TLC: What are some similarities and differences between American and British Blackness and Black womanhood as they are depicted in literature, specifically?

BE: I don’t claim to be an expert on this and I’d hate to generalize, but I can talk more widely about the differences between the U.K. Black experience and its American counterpart. The recorded history of Black Britain goes back to the Roman occupation of two thousand years ago (something I wrote about in my 2001 novel, The Emperor’s Babe and picks up in a big way from the 16th century, but we don’t have Black ancestry here with unbroken lineage beyond the 12th century.

I can count the number of Black British women novelists publishing today on two hands.

Most people of color in the U.K. arrived post-WWII so our lived history is very recent compared to America’s history of four hundred plus years of African Americans. We are also a small minority in terms of race in this country. There are about 2 million people of African descent here, as opposed to some 40 million in the U.S. This is reflected in our literature, with little of it and most of which was very male-dominated until the 90s, with Black women putting in rare appearances, most notably in the works of Nigerian novelist, Buchi Emecheta, who migrated to the U.K. in the 60s.

It’s really only in the past 20 years that we’ve seen more Black female presence in U.K. literature, but certainly not enough of it. I can count the number of Black British women novelists publishing today on two hands. The same can’t be said for the U.S. In the 90s young Black British women writers were writing similarly young protagonists in coming-of-age novels. Most of those writers disappeared. Since then we’ve had a few writers writing Black female protagonists who are still mainly young, also urban and contemporary. African American women’s fiction and literature—which so inspired my younger self—far outperforms our own production here in the U.K. in terms of the quantity of this work. One of my aims with Girl, Woman, Other was to break through these limitations. I think any wider comparison with the U.S. will require something of an academic thesis.

TLC: In your interview with the New York Times, you talk about writing about the African diaspora. Girl, Woman, Other, are stories about womxn whose parents or grandparents immigrated or worked in England in the 19th and 20th centuries. Dominique was the only character where it was mentioned that her ancestry could be traced back to slavery and Hattie’s lineage included slave traders, but otherwise, that part of the diaspora is not explored very much.

Coming from an American perspective where so much of our literature involves slavery, even when it is about other aspects of the diaspora, I am curious about your decision not to touch heavily upon the impact of slavery for Black British people—slavery in England and the slave trade outside of it involving the English.

BE: I’m not sure why my novel should draw more on the slave trade when it’s not a novel looking that deeply into British history. And if there’s one aspect of Black British history that continues to be mined in all media, it’s the transatlantic slave trade, to the extent that it alone is synonymous with our history, even though, as I said earlier, our history goes much deeper. My novel is about British women living in the 20th and 21st centuries, and it delves to some extent into their ancestry but it’s touch on slavery is light, as it should be. Britain was a major player in the transatlantic slave trade but there weren’t that many slaves living in the U.K., rather they were in the West Indies. Some of the women in my novel have Caribbean origins and some have direct African origins. Many, many writers continue to explore the slave trade and indeed my own 2008 novel, Blonde Roots, is all about slavery—a satirical inversion of this slave trade where Africans enslave Europeans. It’s very much an indictment of Britain’s involvement in the slave trade. My focus with Girl, Woman, Other was to explore so many more areas of our lives that go under the radar.