[Warning: The following post contains MAJOR spoilers for all eight episodes of Good American Family.]

Good American Family, by its very existence, is another part of the media-frenzied saga of Natalia Grace (Imogen Faith Reid in the series). The fact of its meta relevance loomed large for the co-showrunners of the miniseries, Katie Robbins and Sarah Sutherland, from the series’ very inception. However, Robbins, who created the miniseries for Hulu, and Sutherland both embraced the opportunity to employ some of the stylistic elements of their former collaboration, The Affair, to truly showcase the finer details of what happened and put audiences into the shoes of everyone involved, however contradictory those perspectives truly were.

The show’s structure — switching from the perspectives of adoptive parents Kristine (Ellen Pompeo) and Michael Barnett (Mark Duplass) to that of Natalia halfway through — has a dizzying effect on its audience, and in the finale, we’re left wanting so much more … at least, in the way of justice for Natalia.

The finale finally puts the Barnetts in court, but the case against them is toothless once the judge decides not to allow Natalia’s true age to become part of the record. Instead, the Barnetts walk free — at least, as free as one can be after everything they’ve done. They both remain in a state of denial after it’s done, but there are slivers of justice for each. Michael has a near-breakdown over the realization of what he’s gone along with in believing Kristine, and Kristine loses her closest friend and even the respect of her favorite son over it. Plus, well, there’s a new show out there called Good American Family that painstakingly recreates some truly gutting things about what the Barnetts did to Natalia Grace, and it stars some A-list television stars and one heartbreakingly effective newcomer in the central role.

To break down the season and the finale, TV Insider caught up with Katie Robbins and Sarah Sutherland!

Did anybody involved in this story participate in your creation of events?

Katie Robbins: No, no.

So how did you go about doing the research? Did you have to just look through court documents or dig up personal family files?

Robbins: We had an incredible, crackerjack research team, led by a researcher called Reeva Mandelbaum, who was on the ground in Indiana [and] was there for a lot of the trials. So we were lucky enough to have access to depositions, and court documents, and medical records, and Facebook messages, and text messages, and on and on and on and on.

There’s a scene in Episode 8 where there are these printouts of all of the Facebook messages, and those are a literal representation of how many Facebook messages there were and how many Facebook messages our incredible team, including Reeva and our support staff who were just the best people in the world, dug through. So it was because of that research that we were able to tell this story.

Disney / Ser Baffo

Did either of you know going into it that so much of the undercurrent would be this injustice in the legal system aspect of it?

Robbins: By the time we got into the research and understood the extent of the story, yes, absolutely. I mean, we knew that that’s what it was about for us, and we greatly hoped that that would be what would land with our audience.

When was the point that you decided you wanted to do flipped perspectives and do this half and half?

Robbins: That was the idea from the beginning. So Hulu first came to me with the idea of doing a show, a narrative telling of this story, back in 2020. And, at the time, there wasn’t that much. I mean, it was out there, but it wasn’t as deeply embedded in the popular culture as it is now. And so I did a lot of research and read articles, and I was so struck by the fact that, depending on whose version of the story you were reading, it’s completely influenced how you saw what had happened. So you’d read an interview with like one set of the people involved, you’d be like, “Oh my gosh, this is what it is!” And then you’d read another one, you’d be like, “No, no, no, I was totally wrong, it’s this.”

And so, from the beginning, I wanted to use this as a way of talking about perspective. So it was always that the first four episodes would be told from Kristine and Michael’s perspective and inspired by their allegations and that you would end Episode 4 kind of on one side of the door with them, being like, “Phew, we’ve gotten the hell out of dodge. We’re safe.” And [we’d] then start out on the other side of the door in Episode 5. Whether people realize it or not, that scene in Episode 5 when we’re with Natalia, it’s the first time we’ve been alone in a scene with Natalia over the course of the whole series, and so finally, like being with her as her own person, seeing her from her perspective, and realizing that she’s still acting “as a child,” and realizing, no, no, she’s not acting. That’s who she is. She’s not doing it to perform for anybody — and suddenly having to question all of the things we’ve been seeing in Episodes 1 through 4. So that was always the idea.

But then, one of the things that was interesting was, as we started to get all of this research in, and it started to become clear that there was empirical medical proof of her age, the idea of perspective within the series started to shift and it became like, those first four episodes are the allegations as opposed to like a pure perspective in the way of The Affair, which is the show that Sarah and I met doing. But the idea of narrative perspective was always really essential to the telling of this show.

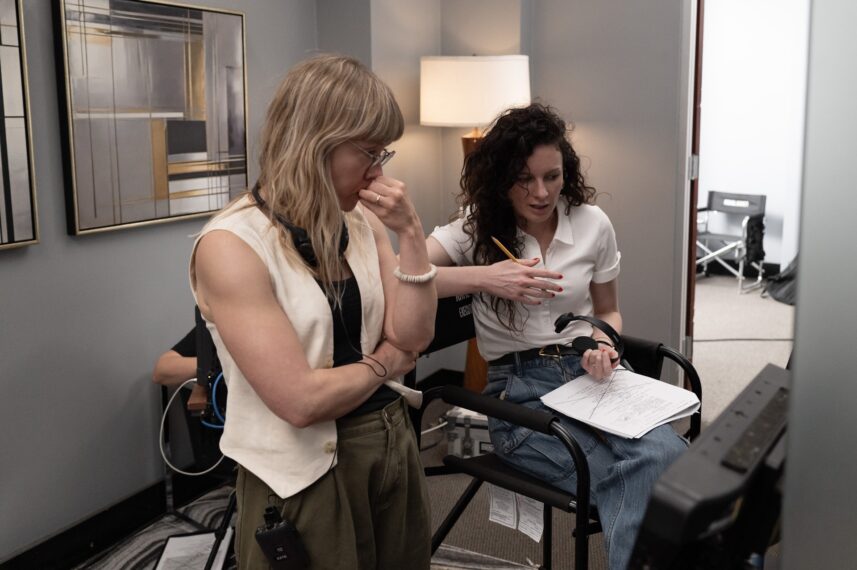

Katie Robbins and Sarah Sutherland on ‘Good American Family’ set / Cr. Hulu

Can you talk about how that particular storytelling structure also gives kind of an indictment of the viewer and how you feel?

Robbins: Yeah. I think that the goal was always that you would watch those first four episodes [and] lean in. They are told in a slightly more melodramatic, campy almost way because there is so much melodrama and heightened feeling to the allegations that are made about Natalia, like being at the foot of the bed with a knife and throwing stuff into the street. It is the stuff of horror movies. And so you lean in, and you’re worried, and you’re scared, and you’re with them. And then suddenly, the rug gets pulled out from under you, and the way that perspective is set up is to kind of push the audience towards grappling with the question of our own biases around disability, our own biases around whose stories get believed and whose don’t, whose stories get to be told and whose don’t.

And it’s been amazing watching the response to that turn in Episode 5 and beyond in 6 and 7 — and, hopefully, 8 when that comes out — of people on social media being like, “Oh my God, I completely was on board with these first four episodes, and now all of a sudden, I feel really bad. Why did I think that?” And so watching people sort of not only admit that maybe they were wrong about something, but also that they feel badly about it, and also questioning why they came to believe what they believed, has been incredible. And I think it’s something that is rare in life, to admit any kind of misunderstanding and then even further to grapple with why they have that misunderstanding. And one of the things that I think we all need to be doing in this moment and in general is to be asking questions and to ask why we believe what we believe and if maybe there are more questions and more nuance beneath the surface of the black and white.

What does it feel like to be part of that story now because, as your series notes, the media representations of this case were played with by these people? And so this series naturally dovetails into that. Can you talk about kind of that meta element of this?

Sarah Sutherland: We felt a lot of pressure to tell the story in a way that elucidated things that had not yet been cleared. And I think it’s noteworthy that even now, even after the show had been fully wrapped and was ready to release, there are articles that are coming out that are asking like, “Is she a villain or is she not? Is she a villain or victim?” And so in terms of the question of, “Should this be a show and should we take the time to put more information out about this thing that people are already talking about,” honestly, we talked about that explicitly. And at the end of the day, the thing that made me feel good about it… was that this was a way to take audiences on a journey toward putting themselves literally in someone else’s shoes, walking through that experience, and then suddenly being put in the other person’s shoes and really [say], “Oh, wait.” And then in [Episodes] 7 and 8, the idea is that you go back and forth between the two, and you start to realize there’s an extensive corroboration for Natalia’s version of events, and there’s a shocking lack of corroboration for the Barnetts’ version of events…. Just speaking vulnerably, the hope was that that actually does change people’s minds and change the narrative in a way that wouldn’t have been true in a different format. And I think that to Katie’s great credit, her original idea had the skeleton of that from the very, very beginning because I think it’s the way that she interacts with the world and is interested in understanding people, and the kind of magic trick only became harder and also more important the more we knew, which was terrifying.

Can we talk about casting Imogen because as we know, this was her first role and you guys asked her to do so much? How did you choose this actress to do such a complicated performance?

Robbins: So, after I finished writing the pilot and the story format, going through the way that the perspective would work in the episodes, it was 2021, and Hulu was like, “We want to make this show. We were really excited. However, we can’t order it to series until we know that we have somebody to play Natalia.” So the series order was contingent on casting Natalia.

So it was like, “Okay, great. Please go find somebody who has dwarfism” — because we knew we wanted to cast authentically. “Please find somebody who can play from 7 [years old] to 19 biologically but then from the Barnetts’ perspective in those first four episodes, be even older. [Find someone who] can play the tremendous range of being manipulative and conniving in those first few episodes and then incredibly vulnerable and grappling with trauma while still retaining this sense of childish playfulness, and then a sense of righteous indignation, in the later episodes, but also be like very charming and charismatic and all of these things. So go find that person and then we’ll order it, we’ll pick it up.” So it’s, you know, just your regular casting call. [Laughs.]

Luckily, we had an incredible casting team, an extraordinary group who did an international casting search and sent us a lot of tapes. [There] were tons of really wonderfully talented actresses, but Immy’s rose to the top by leaps and bounds. We saw this tape, and it was a scene from the pilot, the beach cafe scene, I think, and we were just like, “Oh my gosh, who is this person?”

And she’s based in the U.K. so she would slate in [with] her name in British English and then suddenly like switch into this American accent and like that in itself was just like, “Whoa.” It was amazing. So we did a series of callbacks, and we were like, “Okay, this is gonna work. It’s one of these amazing casting stories from like the MGM era, like ‘a star is born’ kind of thing.” We Zoomed with her shortly before she came to the States — she’d never been to this country before, she’d never been to L.A. She’d never played a part of this kind of magnitude. So there was so much anxiety all around of like, “How can you ask somebody to hold this on their shoulders?” And we Zoomed with her… and her nervousness about it was all about doing justice to this story. She just really wanted to make sure that in telling this story and playing this role, she would do justice to Natalia. That was the way in which she was entering this process. [Then it] was like, “Okay, we’re just gonna all hold hands, and we’re gonna do this, and we’re gonna support you in however we can,” and she just rose to the occasion in a way that it was…. When we were filming Episode 5 and that first episode from Natalia’s perspective, there were seasoned crew members on set crying, watching her because everybody was just so moved by her performance. It’s amazing.

Were there any other performances from the cast that felt just particularly revelatory?

Sutherland: I mean, the most revelatory thing was that every single cast member was shockingly good, and also in really, really different ways. We have Ellen, who’s this titan of industry with television, who’s such a total pro, I mean, such a star and playing in a completely different role. That was exceptional and so exciting to watch. And Mark, I’ve been a fan of Mark’s work forever. I think of him as forging a path in the type of television and storytelling that I love. And so to get to see him and to meet him, and he just has such humility despite him being clearly brilliant and able to do so much, that was extraordinary. And, I mean, Christina Hendricks — I haven’t revealed this to her, but Mad Men, I’ve rewatched Mad Men three or four times. I feel as if I know her. Of course, I don’t. And I mean, this role is just so different from anything that I’d seen her in before. To have such high expectations for someone and then have them blow those away, it was all so amazing. And Dule Hill, Jerod Haynes, Kim Shaw, and Sarayu Blue….

With Sarayu Blue, we talked about the character Val, which is short for Velika, is the surrogate for the audience because she, in the beginning, laps up everything Kristine’s saying in the same way that we do. We’re like, “Yeah, she’s great, she’s taking care of the kid, da da da da,” and then slowly but surely, she has to come to terms with the fact that her friend might actually have been [abusive], and that admission was really interesting. That scene in the kitchen was a really revelatory one, I think, for all of us on set, ’cause it felt so cathartic for someone to name it to Kristine’s face, and I think Sarayu just did a beautiful job with that… I’m not bulls**tting you. These people are all extremely good at what they do, and I feel so humbled to get to have seen them at work. They’re awesome.

Disney / Ser Baffo

That’s a good segue honestly to another question I have. Just after that scene with Sarayu and Ellen, when she finally calls her out on it, she goes home, and it seems like maybe her worst-case scenario is living with her mother alone and being penniless. Can you talk about bringing that closure that at least she had some consequence?

Robbins: As Sarah was saying, in terms of that scene, Val’s character has been kind of a surrogate for the audience throughout the season. She is completely on board with the version of the story told in Episodes 1 through 4. She’s so much a part of that that when Natalia shows up in Episode 5, she’s like, “You’re a monster… you’ve kidnapped this child. I believe what I’ve been told. I haven’t asked questions.” And then suddenly we get her into the courtroom in Episode 8, and she’s watching that unfold. And I think it’s an experience similar to what we were talking about before with people’s reactions on social media of being like, “Holy s**t. Maybe I was wrong. I feel guilty and why?” … Then, Kristine in that moment isn’t able or willing to answer those questions, and she does what she’s been doing throughout the season — and she’s done that previously with the lawyers in the beginning of Episode 8, and she’s done it with Michael, and their fight in at Val’s house, and then she does it again with Jacob in the car, as he’s saying to her, “Mom, the way in which Natalia’s birth mother talks about Natalia is the way in which you talked about me.”

Kristine, in that moment, isn’t able to hear that. Then, she gets to Michael’s house. Everybody says, “No, we don’t want to be with you.” And so she’s forced to leave and go back to her mom’s, and sort of cycling back to Episode 4, she said to her mom in that episode, “You are all alone because you refuse to see anything. You refuse to admit that things were hard for us. You refuse to admit that we were in danger, and now you’re all alone.” And now we see Kristine all alone, going back to the one person who will let her in. And then she goes back and she watches this video of Anna Gava, of Natalia’s birth mother talking about Natalia in the way that she did about Jacob, that the doctor said that she should just give up on her child. And we’ve heard, at that point, Kristine tell that story about Jacob so many times, that the doctors told her to give up on him and she wouldn’t. And so hearing that from another mother, hearing kind of her own story echoed back and reflected back at her, there’s like the smallest little moment of something that gets into our version of the story. And then she closes the computer and can’t have it because it’s such a painful thing to kind of try to grapple with.

There’s something similar with Michael, too, in the hotel room where he lets it in for a second, and she kind of coaxes it out of him. And in the end, when Natalia confronts him, he’s pretty much like, “Well, I’m a victim, too.” Can you talk about choosing to do that because there are so many opportunities for this guy to rise to the occasion, and he refuses to over and over again?

Sutherland: Yeah, I think that a big theme for the show and for this episode is cognitive dissonance and how powerful it is. This is the moment where everybody’s suddenly — their identities are sort of split into two. We talked a lot about how for both Kristine and Michael, for their identities as good people to stay intact, it means that Natalia must be a bad person and vice versa. So this one makes it a very juicy thing to write, but it’s also just so human that we all have these identities about ourselves, and I think that goal for him, being a good father, being a good person, is the thing that keeps him feeling like he can overcome his doubts about existence, and I think that that’s a very familiar thing. He’s an extreme version of that, but I think that everybody, anyone I know well, can admit to something similar… While you’re watching it, it seems so obvious to just be able to say, “You were a kid, I’m sorry.” And he can’t because to do that would be to say, “You’re right, I’m not who I want to be.” And I think he is such an interesting character because he goes back and forth. He sees it, and then he closes his eyes, and Kristine’s reaction is more to just keep her eyes closed except for that tiny little moment that Katie was referencing. That theme I find so personally haunting, and yet also really true. And maybe the degree to which we can make it feel less haunting might make us all a little bit better.

This is a story that continues to play out in real life. There are new stories about the Mans family, for example, and it’s a little bit of history repeating with this double perspective stuff in those headlines. Is there any chance you are thinking about if there is more story to tell here?

Robbins: This series ends very specifically where it does … at the end of that trial, when there is empirical, scientific fact [available about] Natalia’s age, and having that not change anything in the court of law. Having that be not admissible in the court of law really lands this horrifying idea — in a show that grapples with horror tropes — that is the most kind of horrifying thing at the end of the day, that that doesn’t matter. That doesn’t change anything. And so it very specifically ends in the aftermath of that because we really wanted to land that idea, sharply. And it just becomes kind of even more relevant every day, that idea of the ways in which the justice system can be flawed and fail people. So that felt really important. I think that to do an additional story here, there would need to be a reason, something to say with it. And never say never, but that would be the thing: “Why tell it?”

Good American Family, Streaming Now, Hulu

Read the original article here