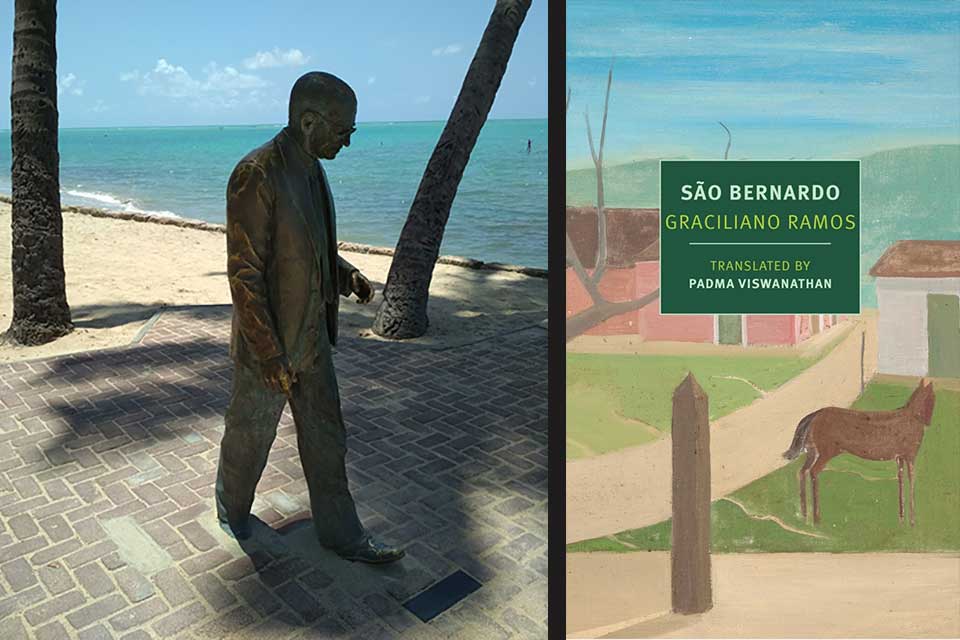

In her new translation of Graciliano Ramos’s São Bernardo, forthcoming early next month from New York Review Books, Padma Viswanathan reproduces the linguistic edges of Ramos’s quicksilver prose in hopes of raising Ramos’s profile in the anglophone world.

Graciliano Ramos worked hard. Born in 1890 and raised in small towns in the interior of Alagoas, in northeastern Brazil, he moved south to Rio in his twenties in hopes of breaking into newspapers but felt compelled to return home, a year later, when multiple family members fell victim to the plague. He set up shop—literally—in Palmeira dos Indios, a midsize town where his father also was a shopkeeper, and reestablished the night school he had been running before he left. Though he was an autodidact, he was a cultivated and exacting one, reading in English, French, and Italian. The region’s schools were poor, but a number of his students went on to professional success.

In 1928, under duress from a couple of the region’s strongmen, he allowed his city to elect him mayor, a position he didn’t covet. For one thing, his predecessor was in fact his predeceased: shot to death in a dispute with a tax collector, himself shot and killed shortly after. For another, Ramos perhaps knew he would be as uncompromising in his mayoral duties as he was in his teaching and writing. He allowed himself to be muscled into office but then started cleaning up: installing public washrooms; making it illegal to let pigs and goats forage on the streets; passing laws against corruption. When his own father objected to the antipig ruling, Ramos responded, “Mayors don’t have fathers.”

He is still considered to have been an exceptionally good administrator (perhaps particularly for a writer), though he left the post after two years. This term, however, changed his life: one of his two drily funny annual reports (which sketched the bureaucratic demands of his tenure and his accomplishments as well as the dynamics of small-town life in this remote area just before the Depression and the Vargas dictatorship) somehow made its way to the press, attracting national attention. Augusto Frederico Schmidt, a poet, publisher, and key figure in Brazilian modernism, contacted Ramos to ask if he was writing anything else. He was: he pulled a complete novel, Caetés, out of a drawer in response. It was published to acclaim, and, within a few years, Ramos was one of Brazil’s best-known novelists.

In the meantime, his father’s store, which he had taken over, went belly-up, but Ramos shortly after became director of public education for the state of Alagoas. He worked and wrote; he worked hard; he wrote harder.

“Writing should be done the way Alagoan laundry-women carry out their task,” he famously said in a 1948 interview. “They start with an initial washing, wetting the dirty clothes at the edge of a pond or stream, wringing out the cloth, wetting it again, then again wringing it. They blue it and soap it, then wring it, once, twice. After rinsing it, they wet it again, this time by throwing water on it. They beat the cloth on a slab or rock, then wring it again and again, wringing it until not a single drop of water drips from the cloth. Only after having done all this do they hang the clean clothes on a washline to dry.”

It makes sense that Ramos would describe writing in terms of hard physical labor, but particularly a sort of work necessary and satisfying in the short term despite a long-term futility—those clothes, after all, are destined to get dirty, beginning the cycle again. All four of his novels, published in the 1930s, are underpinned by cyclical dramatic ironies of labor, ambition, and failure: the dignity and indignity of keeping body and soul together; the possibility of collapse always near at hand.

All four of his novels, published in the 1930s, are underpinned by cyclical dramatic ironies of labor, ambition, and failure: the dignity and indignity of keeping body and soul together; the possibility of collapse always near at hand.

São Bernardo, the novel I have translated, tells the story of Sr. Paulo Honório, a former laborer who buys and restores the decrepit property where he was once a field hand. Sr. Paulo learns to read only as an adult, as a result of a stint in jail. After the tragic loss of his wife and a serious downturn in his fortunes, Sr. Paulo writes a memoir, which he calls São Bernardo after his ranch. And yet, at various points in his narrative, he disparages literary pursuits and elevated language. Sitting in bourgeois salons, surrounded by readers of novels, he sees himself as a truth-teller, a man of the world.

So, although Sr. Paulo has acquired the ability to write, he disdains it. What he respects is the hard labor of building and acquisition—honest work, even when, as in his case, the path to success is paved with threats, deceptions, even murder. He is tireless in his efforts to buy the ranch and restore it. “At first, capital kept giving me the slip though I chased it nonstop,” he recounts, “traveling the backlands, trading in hammocks, livestock, pictures, rosaries, knick-knacks, winning some here, losing out there, working on credit, signing notes, carrying out extremely complicated operations. I went hungry and thirsty, slept in the dry sand of riverbeds, fought people who only spoke in shouts, and sealed commercial transactions with loaded guns.” When he acquires the ranch—repossessing it after having lured its dissipated owner into taking loans from him—he plants orchards, paves a market road, builds a dam, all while educating himself on chicken and cattle breeds.

Sr. Paulo characterizes the work of the mind—literature, journalism, law—as decadent and useless or, worse, pernicious and parasitic. By this logic, if he kept body and soul together by acquiring São Bernardo, he separates them again by writing the story of how he did it. Still, alone with a pen in his hand, he has to acknowledge that writing might be the hardest work yet. “Seated here at the dining table, smoking a pipe and drinking coffee, I sometimes pause this slow work, look out at the orange-tree leaves darkened by night, and say to myself, a pen is a heavy object.” Writing is the labor that might defeat him, and his limitations with language have already been brought home in another way: his wife, Madalena, was a writer, and his failure to understand her last piece of writing precipitates the final tragedy of their marriage.

These facets of the book—irony, illiteracy, and the limits of language—shaped my approach to translating it. Where it was tempting to smooth a jagged transition or an awkward sentence, I have tried to preserve its roughness or strangeness when those qualities seem to be present in the original. Most educated Brazilians—the class Sr. Paulo is writing for but not the class from which he comes—wouldn’t be familiar with most of the idioms in the book. This was vividly reinforced when I was consulting with a Brazilian friend, Sheila Ribeiro, a brilliant and determined interlocutor, who was stumped by many of the expressions. Finally, she said, in a flash of insight, that she believed that Ramos possibly intended for readers occasionally to feel thwarted by Sr. Paulo’s way of talking. “Graciliano is a demon!” she shouted. “I love him!”

I didn’t need to speculate on Ramos’s intentions to recognize that Sheila’s analysis made perfect sense. This is the story, after all, of a man in a unique and lonely position, a position he reflects on at his own story’s close: how, had he remained illiterate, he might not have been estranged both from his own kind and from himself. He has never tried to gain entrance into the bourgeois world: he doesn’t crave it and knows it is blocked to him. His successes, in other words, have made his life impossible.

So if an expression is unfamiliar to Brazilians, I would try to keep that quality, sometimes by translating it literally, whereas if it is a common expression in Brazilian Portuguese but strange to us, I have usually rendered it as a common North American idiom. I also tried in other ways to replicate the linguistic breadth of the book. Various Brazilian critics have written on lexical choices in Ramos’s novels, and the ways that these convey the modes of speech and thought of the region where his novels are set. His translators, they note, have not always been careful to respect this.

I owe a huge debt of gratitude to São Bernardo’s previous English-language translator, R. L. Scott-Buccleuch—he certainly saved me from committing any more errors in my own translation than I have. But he saw the book differently from me, opting to normalize many local expressions, making the narrative—and, by extension, Sr. Paulo—more accessible to readers. He also seemed to me insufficiently concerned with the book’s humor.

Early on, for example, Sr. Paulo relates the main incident that changes his life: he gets into a fight over a young woman at a party, is thrown in jail, and emerges both newly literate and with the ambition to buy and restore S. Bernardo. The original passage is full of lightness and sexual innuendo and concludes with an extraordinarily layered sentence: “. . . levei um surra de cipó-de-boi, tomei cabacinho e estive de molho, pubo, três anos, nove meses e quinze dias na cadeia . . .” Here is a quick parsing: “Levei uma surro de cipó-de-boi” means took a beating from a bullwhip; “tomei cabacinho” means to take an herbal medicine, possibly drunk from a calabash, but “cabacinho” is also slang—very widely used—for virginity; “estive de molho” means to soak, as in a gravy, but is also an expression that means to rest up when one is sick; “pubo” means rotten but has an aural echo of “puberty,” and the last words describe the exact length of his sentence. This is the paragraph when our antihero effectively comes of age.

I translated this as “I was beaten with a bullwhip, took my medicine and stewed in my own juices, rotting in jail for three years, nine months, and fifteen days.” This is Scott-Buccleuch’s version: “When I recovered from the lashing they gave me, I spent three years, nine months and fifteen days rotting in jail.”

My predecessor might have seen such simplifications as a service to the author—he would go on to become more aggressive in this kind of translating, quietly cutting whole chapters of digressions out of Machado de Assis’s Dom Casmurro—but I think they were a disservice to the book. Much of São Bernardo’s genius is in the ways that Sr. Paulo’s actions, attitudes, and language lure us into uncomfortable regions of simultaneous sympathy and disidentification. To soften his linguistic edges is to dull the book’s light.

Much of São Bernardo’s genius is in the ways that Sr. Paulo’s actions, attitudes, and language lure us into uncomfortable regions of simultaneous sympathy and disidentification. To soften his linguistic edges is to dull the book’s light.

This is particularly painful to contemplate because, as the American critic Fred P. Ellison notes, “We have reason to suspect that the choice of an adjective may have caused Ramos ‘to sweat in agony,’ as has been said of Flaubert. . . . With Ramos, language is a precision tool with which effects hitherto unrecorded in Brazilian literature have been made.” Ellison quotes Guilherme de Figueiredo, marveling on similar matters: “The constant polishing of his style . . . lends almost astounding force to a mere sentence, to a mere word. . . . His expressions are immutable in their framework.”[1]

Pounding and wringing; constantly polishing; wielding language like a precision tool as he sweats in agony: regardless of whether I succeeded, I thought Ramos deserved for his translator to sweat her choices as much he did.

In the course of translating him, I learned that there is a history of North American critical contortions trying to fit Graciliano into a social-realist box, of downplaying the ironies of situation and character woven tightly into the novels’ fabric. I suspected that not just critics but translators, too, might have succumbed to this bias. If his translators didn’t recognize how intrinsic Ramos’s quicksilver prose is to the quality of his works, this might account at least partially for why he has been marginalized internationally, relegated to the ranks of the regional, the minor.

If his translators didn’t recognize how intrinsic Ramos’s quicksilver prose is to the quality of his works, this might account at least partially for why he has been marginalized internationally, relegated to the ranks of the regional, the minor.

All educated Brazilians have read at least one of Ramos’s books, and more avid readers will readily name a favorite among his novels. In 1941 a national literary poll in Brazil named him one of that country’s ten greatest novelists—one of only four living authors on the list—and his reputation seems only to have increased in the sixty years since his death, with all his books still in print, special issues on anniversaries, and beautiful boxed sets. In a 2012 essay about Ramos in Asymptote, Paulo Scott, a rising Brazilian literary star, starts by mentioning how little-known Ramos is outside Brazil. After a close consideration of his work, Scott says, “It’s impossible to read and contextualize contemporary Brazilian writers without considering Ramos, who . . . made great strides toward a spare, elegant narrative that influences my way of writing to this day, and, I’m certain, the writing of the majority of Brazilian writers who are gaining renown and readers today, not only in Brazil, but throughout the world.”

Rachel de Queiroz, another Brazilian novelist on that top-ten list of 1941, praised Ramos’s “vaguely brilliant quick tone.” It’s been an honor to bask in that quick brilliance and to try to turn its glow toward English readers in hopes of raising Ramos’s profile in the anglophone world.

Fayetteville, Arkansas

Editorial note: This essay was adapted in part from the translator’s afterword to be included in São Bernardo.