If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I am a Black person who doesn’t know how to play spades. That’s important, sort of, but less important, certainly, than the fact that reading about Black folks playing spades makes the game feel almost ancestral in its familiarity to me. More specifically, the familiarity I feel when invited into a game as Hanif Abdurraqib writes about it: “Oh friends—I most love who you become when there are cards in your hands. How limitless our love for one another can be with our guards down.”

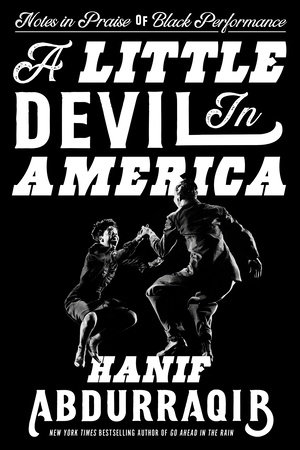

That sense of limitlessness wraps itself around every essay in Abdurraqib’s newest book, A Little Devil in America: Notes in Praise of Black Performance. In it, he writes about Black performance in America—from Great Depression-era dance marathons to the enduring cool of Don Cornelius to the art of Mike Tyson entering a boxing ring—with both great reverence and rigorous analysis. The book, in the way Abdurraqib’s work so often does, erects monuments to our should-be legends and our unignorable icons alike, and paints an expansive, deeply felt portrait of the history of Black artistry.

Hanif Abdurraqib is a poet, essayist and cultural critic from Columbus, Ohio. He is the author of the poetry collections The Crown Ain’t Worth Much and A Fortune for Your Disaster, the essay collection They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us, and the New York Times bestselling Go Ahead in the Rain: Notes to A Tribe Called Quest. I had the great honor of speaking with Abdurraqib about sports as a mode of performance, finding joy in research, and the generation-spanning power of a Soul Train line.

Leah Johnson: This book felt really special to me as I read it. Fresh, I guess in a way that not every book I read feels. Did you get the sense as you were working on it that you were breaking new ground in your writing or in the tradition?

Hanif Abdurraqib: Oh, no, not at all (though I appreciate your high praise there!)—I think a thing I always try to remember is that I’m never the first to do anything, especially when writing within the Black tradition of storytelling, and reformatting genre/shape of work. It feels best when I frame myself within a lineage of workers who have (and still are) doing the kind of work that excites and informs my own. It feels more honest in that way. I will say that, more than with my other books, I felt like this one was guided by some of the voices and ancestors it was populated by, and some who don’t make an appearance at all, or make small ones. I feel like Toni Morrison, especially, guided some of my organizing principles.

LJ: I’m not trying to gas you up here, but I did spend a lot of time crying and crafting essay-specific playlists as I read this, which to me is the marker of a great book. If you had to choose one artist’s work to be played alongside the reading of A Little Devil in America—sort of like matching a cheese to the perfect wine—whose body of work would it be?

HA: This is such a good question, and I’ve thought about it a lot because I’m actually working on a book-specific playlist, to honor the tradition of doing book-specific playlists that I’ve done with all of my books. I really want to push people towards Merry Clayton’s solo work, because I think it is so underappreciated, but really gets to the heart of what so much of this book is wrestling with. Her voice holds so much triumph, it holds so much gospel, there’s so much light coming through the cracks of it. It is easy to paint her story as a story of only pain, but her work refuses it, she refuses it.

LJ: In a conversation between you and Dev Hynes recently, you asked him about his relationship to dance as it relates to his compositional ability, and I’d actually like to turn that question around on you. Considering this book is so interested in the art of movement, what is it about dance that compels you to interrogate it so thoroughly, and how would you say it informs your larger body of work?

HA: I think because I cannot dance well, I find myself drawn to dance. I’m being serious, truly. I can dance well enough to survive on a dance floor, but not well enough to awe anyone with my moves. I especially know and appreciate when it is my time on a dance floor, and when it is time for me to get out of the way and let someone more equipped than I am cut up. If there is a way this informs my work at all, it is because I think I am so in-tune with ideas of restraint. Some of this comes from my life playing sports, too—which Dev and I also riffed on a bit. I think so much of me is trained to understand what I’m capable of and what I’m less equipped to do. And with that comes an understanding of how I can use the former to strengthen the moments where I’m wobbling along the latter.

LJ: Sports as a mode of performance is something that comes up a lot in your work, and feels in line with the way you write about the history of dance marathons at the beginning of this book. Where do sports and music intersect for you?

My favorite musicians are usually not the people at the front of the band. It’s the confident player on the side, who doesn’t speak much, but knows how good they are.

HA: I think there’s something about exhaustion, endurance, and joy that come through in a singular sports performance that also come through in a singular live music performance. I think the sonic highs and lows that can exist within a song, or within an album can be seen playing out in a sport like basketball. Some of my favorite basketball players are guards (sometimes undersized) who shoot a lot. This is probably because I was/am an undersized guard, one who is a bit more tentative about shooting. But it feels like there’s a real miracle in watching someone just fire away at the basket with confidence. There’s something in this, I think. That my favorite musicians are usually not the people at the front of the band. It’s the confident player on the side, who doesn’t speak much, but knows how good they are.

LJ: I’ve read you say that this book was your most joyful writing experience yet. Was the joy in being able to sit with the specific subject matter for an extended period of time, or more in the process of writing it itself?

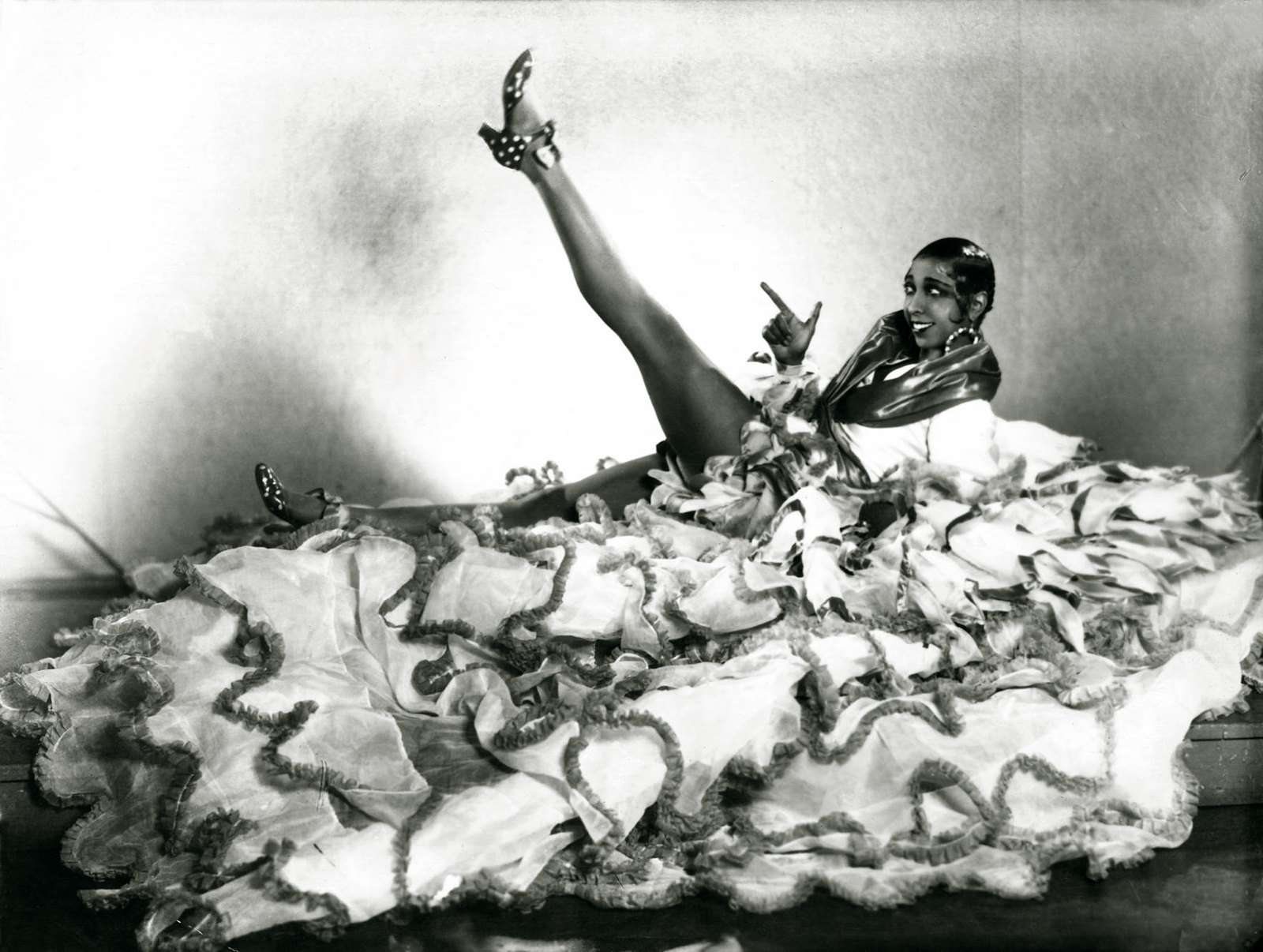

HA: I think both, equally—but there was also immense joy in the very visual research practice of the book. Watching hours of Soul Train footage or watching Josephine Baker’s life and career play out through decades. Having moment after moment of being able to watch something and sit in gratitude for what Black folks have been capable of across time, across eras, before I was born. And what they will certainly still be capable of after I’m long gone.

LJ: You’ve spoken a lot about how involved you are in the processes of choosing your book covers, which absolutely would explain why they are, bar for bar, some of the best in the game. When a reader picks up A Little Devil in America and sees that Leon James and Willa Mae Ricker photo, what sensation did you want the cover to leave them with?

HA: It was important to me that I found a photo that showed a Black person’s face, in complete ecstasy, in the throes of doing something they maybe once thought was unbelievable, or them realizing they’re at the height of their powers, for a brief moment, before coming back down to an earth that is sometimes wretched and sometimes unkind. I was so excited to find these photos of Lindy Hop aerials because it was exactly that sensation. People elevated, off the ground, finding a really quick newer and better world in the air. I loved that, as a thing to center the book on. I don’t love the world as it is currently constructed, and so I have to ascend to a better one, even if I know I’ve got to come down. I want people to look at the photo and be thankful for whatever movement (physical, emotional, or otherwise) they have at their disposal to take them to a better place.

LJ: In, “It Is Safe to Say I Have Lost Many Games of Spades,” you have this line that I couldn’t stop thinking about after I set the book down, where you write that you meet your “enemies with silence and my friends with a symphony of insults.” It made me think about engagement as a type of care. I’m wondering if you think about your work, as you’re in the middle of it, as an extension of love?

It was important to me that I found a photo that showed a Black person’s face, in complete ecstasy for a brief moment, before coming back down to an earth that is sometimes unkind.

HA: I think maybe I most think of my work as a way to remind myself that I am someone who has memories that I will maybe not always be able to hold close, and I want to happily expel them while I still can. Not just for the sake of others who are reading (though I’m happy they’re along for the ride) but very much for myself, and my needs. My understanding that I’ve lived a life that was sometimes good, or sometimes without pain. I suppose that is an extension of love, even if I don’t always mean for it to be.

LJ: We have all these shared cultural artifacts in the Black community, though, as you write in your spades essay as well, a lot of these artifacts are retooled and distilled differently depending on where you grew up. What do you think your relationship to the Midwest has given you in terms of the lens you find yourself examining art through?

HA: I think even calling myself a Black Midwesterner is funny because I live in the middle of Ohio, and Blackness as it presents itself here, in this state, shifts depending on what part of Ohio one is in. Black folks in Cleveland and Black folks in Cincy and Black folks in Columbus are all different—different interests, different routes of migration meaning different investments in place. And that’s just in one state. To say nothing of the upper Midwest, to say nothing of, say, St. Louis. I really cherish that. It reminds me of how vast our multitudes are. Place is fluid—and I say this with someone who has immense love for where I’m from—but the ways Black folks have found each other and the way I’ve found my people along our multiple geographies is fulfilling.

LJ: I’m sure you’re going to get a lot of questions about writing in the middle of a pandemic if you haven’t already. But I have to ask, how has your process shifted, if at all, over the past year?

HA: Well, it does feel good to write from home consistently. I was on the road so much that I was writing from hotels, or airplanes. It felt untenable, in a way. I like the calm of having a desk, having a place to write, having a way to set my table. The poet Vievee Francis talked about this at the first Big Writing Workshop I ever went to. Having a place to set your table, so that when you exit the work, as raw as one might feel in that moment, there are things you love beside you. A photo, a dish of familiar candy, a few crystals (in my case). I have really cherished setting my table.