If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

In 2012, upon the publication of my first novel, Flatscreen, I was asked to write a short essay about Jewish identity for the website myjewishlearning.com. I chose, as my subject, a single line by the early 20th Century Russian Jewish writer Isaac Babel, whose short stories—particularly his autobiographical stories set in the Jewish part of Odessa where my family has roots—had greatly influenced my own work.

The line I chose to write about is Babel’s lovely and cryptic definition of the Jew as someone with “spectacles on his nose and autumn in his heart.” I liked this definition for its figurative vagary—that is, its poetry—but also for its secularity, for its cleaving of Jewish identity from notions of religious practice or faith. As an infrequently practicing non-believer, Babel’s definition reinforced my personal sense of Jewishness as something more closely related to feeling than to doctrine.

I wondered if there was something more intrinsically Jewish about autumn than, say, spring.

In my essay, I tried to unpack what Babel meant by “autumn in his heart.” I wondered if there was something more intrinsically Jewish about autumn than, say, spring. I suggested that perhaps it had something to do with the High Holidays’ occurrence during that season—the dying leaves, the open book of life, the dangling prospect of death—and also with our history as itinerant agrarians. I ended the essay with an anecdote about my favorite holiday, Sukkot, and the beautiful polka-dot sukkah my artist mother once built. I wrote about lying in that sukkah, feeling humbled by the cosmos. I concluded that this feeling was autumn in the heart.

Nearly a decade has passed since I wrote that essay, yet I find myself still thinking about Babel’s definition, and still attempting to parse it. And while, upon rereading that old essay, I’m not as embarrassed as I thought I would be, I’m not entirely convinced by it either. The essay’s ending feels slippery and evasive, offering lightweight mysticism in place of the concrete.

Julian is our first child, but he was not our first pregnancy.

It also occurs to me, upon rereading, that though I pay lip service to the connection between autumn and mortality, I don’t linger on the subject. I was 29 when I wrote the essay, and, with the publication of my novel, I was on the cusp of what felt like the beginning of a life. I had just moved in with my girlfriend, who would later become my wife. Death was not on my mind. I am 39 now and, along with the rest of the world, as we watch the global death toll increase each day, it’s in my thoughts more than ever. But the thing that has most affected my thinking about mortality, and by extension, my thinking about Babel’s definition, was not the death of a friend or loved one, but a birth. Specifically, the birth, three years ago, of my first child, my son Julian.

Julian is our first child, but he was not our first pregnancy. Almost a year to the day before his birth, my wife had a miscarriage. The miscarriage was early, just a few weeks into the pregnancy, but it was still devastating. We were living abroad at the time, in Amsterdam, which added to our feeling of profound vulnerability. We were in a strange place, far from family and community, far from home.

We spent the summer after the miscarriage traveling in Europe. We visited beaches in the South of France, ate pasta in Italy, and took the Game of Thrones tour of Dubrovnik. The last stop before returning to the States was my ancestral homeland of Poland, where we visited Auschwitz on a sunny August day. Maybe it speaks to the state I was in—after the miscarriage— that what upset and surprised me the most was how pretty it was there, at Auschwitz, on this particular day: how green and florid; how scenic its vista of trees. This was evidence, it seemed to me, of nature’s indifference to human suffering. I had always pictured the camps in winter, but it occurred to me, for the first time, that the camp’s prisoners must have seen days like this, beautiful days, even as they were starved, and tortured, and murdered.

The other image that sticks with me from my visit to Auschwitz, is a display case filled with suitcases, many of which had names and addresses handwritten on them. Some of the names were familiar—Adler is one I remember, the same surname as a friend of mine from college—and, in a different sense, the handwriting samples were too. One, with its whimsical curlicues on the tails of certain letters, reminded me of my mother’s. Another’s angled lefty scrawl reminded me of my own. These people had written their names and addresses on their luggage because they expected to one day return home.

When we found out we were pregnant again—we were back in Brooklyn by this point, without health care, or jobs, or an apartment—Sarah and I were understandably concerned about the possibility of another miscarriage. And though, as the pregnancy progressed, we breathed a little easier with each milestone passed—when we first heard the heartbeat, when we first saw our son’s human shape on the sonogram—we couldn’t completely shake the fear that the worst might happen at any moment. I’d hoped that my fear would subside after a healthy baby was born, but I now understand that the fear I’d felt, that omnipresent awareness of the fragility of human life, is simply a condition of being parent.

These people had written their names and addresses on their luggage because they expected to one day return home.

For the first week of his life, our son would only sleep while being held, not in his bassinet. So Sarah and I took turns sleeping in two-hour shifts, while the other sat on the couch watching Netflix and rocking the baby to sleep. When it was my turn to hold him, I’d lightly stroke his scalp, careful not to press too hard on the soft spot in its center which felt, to me, like a persistent reminder of that very fragility. And on one of those nights, at about five or six a.m., as the day’s first sun made itself known in my Brooklyn living room, creeping in shadow across the floor, I found myself reading aloud to Julian from the poem “Little Sleep’s Head Sprouting Hair in the Moonlight” by the definitively not Jewish, American poet Galway Kinnell. The poem, which is quite famous, at least for poem, is narrated by a father and addressed to his young child. It opens with the child’s scream as she wakes from a nightmare, at which point the speaker enters her bedroom to console her. Kinnell writes:

you cling to me

hard,

as if clinging could save us. I think

you think

I will never die

For Kinnell, the small child lives in a kind of perpetual spring, having never seen the leaves fall from the trees or the flower lose its blossoms. His child has not yet learned about death and its inevitability, and so moves, to quote Rilke, “already in eternity, like a fountain.”

It was not only my job, as a parent, I realized as I read this poem aloud, to protect the body of my child, but it was also my job to protect him from the horrible truth of my own mortality. It was my job to keep him, for as long as possible, alive in the illusion that I, his father, would always be there to protect him. And so perhaps, then, what I was faced with, as I cradled my son and read aloud, was not just Julian’s fragility, but my own, not just his mortality, but for the first time, in some deep sense, my own.

As I read on, I found myself weeping. Though I believed the words I was saying—I would “suck the rot” from my son’s fingernails, I would “scrape the rust” from his bones—I knew that these statements were also lies, that there were things in this world from which I could not protect him. And I felt, in that moment, that I understood what it meant to have autumn in my heart.

The question remains: what, if anything, makes this a particularly Jewish feeling? Kinnell was not Jewish, and I’d imagine that the experience I’ve just described—this reckoning with mortality—is a universal one. And yet, I’m not ready to abandon Babel’s definition of the Jew, to cede tribal claim on autumn of the heart.

The literary critic Northrop Frye posits that the biggest difference between the Old Testament and The New Testament is that the New Testament is the story of an individual—Christ—while the Old Testament is a story of a people, The Israelites. From the beginning, then, there has been such a thing as a collective Jewish identity. And though we live in a diaspora that accommodates an increasingly broad range of Jewish experience, something of that identity remains. In part, that identity is rooted in what I’ve just been talking about—this pervasive awareness of mortality—not just on an individual level, but on a cultural one as well.

Babel wrote before the rise of Hitler, but he knew persecution—he was executed by Stalin via firing squad in 1940, at the age of 45. And before Stalin there were The Crusades, and before The Crusades, there was the Roman destruction of the Temples. And it’s not like Jewish persecution ended with the Holocaust either, as anyone who’s read a newspaper over the last few years is aware.

The Jewish condition, then, I might argue, is not so different from the condition of the new parent. It is a condition of anxiety, of omnipresent awareness of the soft spot on the infant’s skull. Only the skull, in this case, is our culture writ large, and we remain in perpetual wait for the next threat to its existence to make itself known.

It was my job to keep him, for as long as possible, alive in the illusion that I, his father, would always be there to protect him.

I keep thinking of another of my favorite Jewish writers, Grace Paley, and particularly of her story, “A Conversation with My Father,” which concludes with the line, “Tragedy, when will you look it in the face?” For the Jew, I think—the bespectacled and autumn-hearted Jew—the answer to this question seems to be: always. We are always looking tragedy in the face.

The day after Trump’s election, I found myself perusing the shelves of a used, English language bookstore in Central Amsterdam. We had arrived in the city a week before, and hardly knew a soul. Sarah was at a hair appointment that she’d made weeks before the election, planning to celebrate the commencement of our European sojourn by dyeing her hair lavender. She’d kept the appointment, not really knowing what else to do; radical stylistic transformation seemed as appropriate a response to the terrible election result as any.

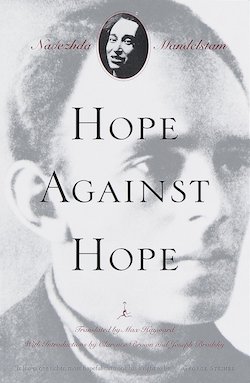

I didn’t know what to do either, so I did what I usually do in such situations, which is to seek out the nearest bookstore at hand. I walked there in the rain, and arrived soaking wet to find a handful of other Americans quietly, mournfully browsing the shelves. This gave me some small solace. In my own browsing, I came upon a battered, mass market paperback edition of Nadezhda Mandelstam’s autobiography, Hope Against Hope, which chronicles her years in exile from Stalin’s regime alongside her husband, the Russian Jewish poet Osip Mandelstam, and then her many more years alone after Osip was arrested and sent to a work camp where he perished.

Osip Mandelstam is my favorite poet, and I had been interested, for a long time, in reading Nadezhda Mandelstam’s autobiography of their life together, but I felt daunted by the book’s length—not only is it nearly five hundred pages long, but the print is very small—and also by what I correctly presumed was its incredible store of pain and sadness. But finding it there, in this bookstore in Amsterdam, on that particular day, felt like fate.

The Jewish condition, then, I might argue, is not so different from the condition of the new parent.

Let me start off by saying that, despite the promise of uplift offered by its title, Hope Against Hope is an incredibly depressing book, even more depressing than I expected it would be, and I was not surprised when I later found out that Nadezhda Mandelstam had followed it with an even lengthier sequel called Hope Abandoned. I found the first few hundred pages of Ms. Mandelstam’s memoir demoralizingly bleak. But while I wouldn’t say that things lighten up after that—the lives of the members of her circle who weren’t murdered by Stalin, often ended in suicide, such as that of the poet Marina Tsvetaeva, who hung herself, leaving behind a note that said, “Forgive me, to go on would be worse”—still, I began to draw inspiration from the author’s endurance in the face of such despair.

Under Stalin’s rule, Osip Mandelstam’s poetry was banned. Any copies of his works that were found were to be destroyed by the NKVD. Mandelstam, for the most part, was not a political poet, but he did write one poem about Stalin, a satirical poem called the “Kremlin Highlander”, which describes, among other things, the fascist leader’s stubby fingers, which Mandelstam compares to live bait. It was for this poem that Mandelstam was arrested, and forced into exile, and later sent to the work camp where he died. Mandelstam wrote the poem —which incidentally, is not one of his great poems—knowing full well that it would lead to his arrest and his demise. He wrote it anyway, and he read it publicly at a number of small gatherings where Stalin’s spies were presumably in attendance, in what was, essentially, an act of suicidal resistance. During his exile in the Southwestern mountain town of Veronezh, Mandelstam would later write a poem that, it seems to me, addresses Stalin directly, and speaks to this act.

Having stripped me of my seas, my flight, my running start,

And given my feet the platform of the violent earth,

How’d you do? Just Great!:

You couldn’t still my moving lips.

Even in exile, after his death, it was too dangerous for Nadezhda Mandelstam to keep copies of her husband’s poems, and due to the real threat that all known copies would be destroyed by Stalin’s forces, she set to memorizing the entire corpus of her husband’s work. She memorized the poems—three or four books worth—and she kept them there, safe in her mind, for roughly twenty years, until she was able to return to Moscow in the early 1960s, after Stalin’s death, and have the poems republished.

This act of devotion—devotion not just to her husband, but to his work, which, I might add, is the work, in my opinion, of one of the twentieth century’s great geniuses—seems to me, to also be a great act of resistance. It seems to me to be an act, in fact, of greater resistance than the poem itself. Because, while the writing of the poem may have been the greater sacrifice, leading, as it did, to its author’s imprisonment and death, Ms. Mandelstam’s feat of memorization provides the greater reward, the preservation of a rare and singular voice, a voice that offers comfort, and beauty, and more than a bit of mystery in its surveys of the human condition. Ms. Mandelstam’s act carried out her husband’s promise that no one still his moving lips. And because of this act, I will one day share these poems with my son, and we will read aloud, to better hear their music, to better feel their rhythm. And when he asks me the difficult questions that, one day, he will inevitably ask—when he asks about love, and when he asks about death, as he pushes the spectacles up off his nose, and looks up at me as if, in my fatherly wisdom, I might have an answer—I will be able to look to these poems, as others might look to scripture, and I will quote to my son:

You can’t untie a boat unmoored.

Fur-shod shadows can’t be heard,

Nor terror, in this life, mastered.Love, what’s left for us, is this:

living remnant, loving revenant, brief kiss.*

And I will tell my son that resistance can take many forms, but that, ultimately, it is an act of endurance, the endurance of one’s singular voice. I will say to him that your voice, like your father’s voice, carries autumn in its heart, and that’s an okay thing, because, autumn leads to winter, and winter leads to spring, and in spring it will rain, and after the rain the flowers will bloom—let nothing, ever, still your moving lips.

*From Christian Wiman’s somewhat unorthodox translation.