If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

“I would be lying if I say my mother’s misery has never given me pleasure.”

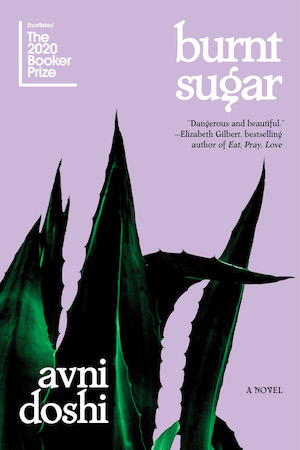

In Avni Doshi’s debut novel, Burnt Sugar, a woman named Antara calls a life coach for help in dealing with her mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. “Reality is something that is co-authored,” the woman tells Antara over the phone, after warning her that her mother’s dementia could shred Antara’s own grasp on reality. These words comfort Antara, but only as an affirmation of what she already knows: memory is unreliable, an easily altered thing.

As Antara struggles with supporting her declining mother, she reveals their complicated relationship—an alternating dance of dependence and loathing that stems from a chaotic childhood following her rebellious mother after she fled her husband for an ashram in Pune. Everyone in Antara’s orbit seems to have their own version of the events of her childhood, creating a knotty web of threads that Antara is trying desperately to unpick.

Doshi’s vivid, propulsive prose and original riff on the links between mothers and daughters, art and science, and influence and agency has earned her a 2020 Booker Prize nomination. I had the pleasure of connecting with Doshi from her home in Dubai, where she currently lives with her husband and two children.

Carrie Mullins: Your novel made me very aware of my own brain in a way that was simultaneously fascinating and disarming. Many of the things that Antara does to understand and improve her mother’s dementia were new to me, and it made me think about how we tend to take our brains for granted when in fact they need upkeep like the rest of our bodies. Were you versed in the science of the brain before writing the novel or did you research it specifically?

Avni Doshi: My grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s four years ago, and I knew nothing about the disease. I was already writing the novel, and memory was a central theme in the story, but as I began to research Alzheimer’s and try to make sense of it, I realized that I was relying on narrative to think around chemical formulas and medical protocols. Slowly the research began to make its way into the book, and the narrator, like me, had to use her art to understand what was happening to her mother.

CM: Of course we can’t talk about the brain without considering the mind half of the mind/body equation. Throughout the book Antara’s mind becomes a kind of adversary that she can’t trust to tell her the truth. Her art project–where she draws the same image from memory to chart the inconsistencies over time–struck me as the perfect way to illustrate how subtly our mind deceives us about its own biases. What drew you to the themes of memory and the unreliable brain?

AD: I’ve been thinking about memory for years. I worked in the art world for a while, and since reading A Hundred Years of Solitude in my 20s, memory and the archival impulse have all inspired my curatorial practice and my art writing. I even did an exhibition where the curatorial note that I presented to artists was from Marquez’s novel. The artist Louise Bourgeois has also been inspirational to me, her work relies deeply on the way memories are transformed, the way they terrorize, their possibility for symbolic value.

CM: The ashram where Tara flees with the young Antara is very creepy. It reminded me of the cultish groups in The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwan or The Girls by Emma Cline in that there can be a strange seductiveness, almost sensuality, to cults, and women in particular seem vulnerable to getting caught.

Tara never should have become a mother. But she lives a life that is assigned to her, marries a certain type of man, enters a loveless marriage, and then decides to leave.

AD: Ashrams have always been in the corner of my vision, for as long as I can remember. When I was young, my mum’s cousin left her life in Pune behind and moved to an ashram in the Himalayan mountains. She was young, about 18, studying to be a doctor. She had no interest in spirituality or ashrams. In fact, her mother belonged to the Osho ashram in Pune, and she thought it was ridiculous, and refused to be a part of it. It never made sense to me why she left. What had pulled her there? I think I was writing into that question with this book.

In Burnt Sugar, it seems clear to me that Tara never should have become a mother. But she lives a life that is assigned to her, marries a certain type of man, enters a loveless marriage, and then decides to leave. What is compelling about the ashram for a woman like Tara? We all have holes, but what particular holes might she be trying to fill?

CM: Burnt Sugar is a tale of mothers and daughters and how fraught that elemental relationship can be, so I was interested to hear that you became a mother yourself after submitting the final manuscript to your editor. I have two small children and I’ve been shocked by how much motherhood changed my perception of certain texts (mostly I have a lot more sympathy for the mother characters!) — did it change how you viewed your depiction of motherhood?

AD: I think I understand the depth of ambivalence you can feel as a mother much more clearly. In fact, I don’t think I’ve known an ambivalence as complex as the maternal one. In a sense, my sympathy for both Antara and Tara has increased: I have a deeper understanding for the kinds of experiences they are having. But in another way, I’m more uneasy about their decisions at time. I have a different sense of what’s at stake. They’re both walking along a cliff—I suppose now I know what they see when they look down. It’s a long way to fall.

CM: From the corner tobacco seller to the Club, Pune comes across so vibrantly in the novel, it almost feels like its own character. Can you tell me a little about your connection to the city?

I don’t think I’ve known an ambivalence as complex as the maternal one.

AD: My mother grew up in Pune and I spent a lot of time there as a child. It’s a second-tier city, not as big and overwhelming as Mumbai or Delhi, but because of the Osho ashram, I think there has always been a lot of interest in Pune. For me, it was a nurturing place because of my family but also a little terrifying. My mother and I would stay there for a month or two every winter, away from my father, who I just adored and couldn’t bear to be away from. So my memories of Pune are tinged with an anxiety, a feeling of powerlessness, which was useful to think about as I was writing. I didn’t want to describe Pune as it is, it was more about mapping a feeling, the Pune of my memories, which is layered with sensory experiences. Especially smell. Memory and smell constantly inform each other in the novel.

CM: I love hearing about an author’s writing process and from what I understand, you wrote the book over the course of many years while living in different places. What is your writing process like? Does it change depending on where you’re living or as time has passed?

AD: I’ve really experimented with this over the years. I’ve tried planning, plotting, I’ve tried going sentence by sentence. I’ve created complex rituals, which have included crystals and candles and sage, and other embarrassing things. I’ve pared everything down, I’ve written by hand. I’ve changed pens. Scrivener seemed interesting for a while but I got over that rather quickly. I’ve tried running and walking because Murakami and Joyce Carol Oates have said I should. Waking up at four in the morning was useful for a time, particularly when I was interested in getting down a certain word count. I’ve realized all of this can work for a while and stop working too.

I try not to be too attached now. I have two little kids and the time for writing is in between the moments I spend with them. But there is something about the time I spend with my kids that grounds me in the present and I think that seems to lead to interesting thoughts and ideas. I use a technique called sense writing that was developed by Madelyn Kent—where basically you enter this parasympathetic state in your nervous system to write. It takes the exertion away somehow, and puts the focus on process rather than product.