Living with chronic illness, whether you are still searching for a diagnosis or long into your own treatment journey, can be a difficult story to chart because there are often complex beginnings and no endings. Every new symptom, doctor’s visit, new medication, and dead-end can feel like false starts and little progress as one learns what their life will be like living with an illness that won’t necessarily kill you, but from which you may never be cured.

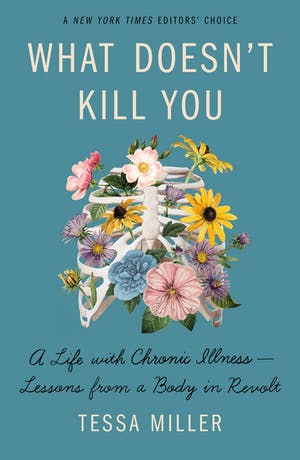

In What Doesn’t Kill You: A Life With Chronic Illness—Lessons from a Body in Revolt, Tessa Miller tells the story of her journey with Crohn’s disease and the knowledge that she has gathered along the way that she hopes to pass on to readers on their own chronic illness journey. As someone with a chronic headache disorder, I considered myself informed about navigating chronic illness, but each chapter challenged me to consider what kind of care I should be seeking from doctors and the many places to seek out community with other people who shared the same diagnosis. There were several points in the book where it was difficult to keep reading, not only because it was difficult to read about Miller’s own pain and vulnerability, but also because she holds up a mirror to the reader and asks us to confront our pain and our own inner dialogues about our bodies that can be so very cruel.

Miller challenges readers to see how medical racism, gender discrimination, poverty and lack of resources for care have made being chronically ill and disabled so much more difficult, but she is sure to leave us with the understanding that it is these systems that are unsustainable, not us and not our bodies.

Leticia Urieta: What was it like tracing the artifacts and origins of your illness for yourself, and then for an audience? What surprised you?

Tessa Miller: It was interesting, to say the least, to use my investigative journalism skills with myself as the subject. I started with a giant dry erase board that I wrote the rough story timeline on, starting with my first hospitalization in 2012. I filled it in as best I could by memory first, and then kept adding as I went through journals, old social media posts, my medical records (which were hundreds of pages I had to request from several different hospitals and doctors), and interviews with my family and my doctors. I was surprised by how much I remembered (especially given the massive amount of opiates I was on during my hospitalizations!), but I was surprised, too, but how much my brain had buried, I think, in an attempt to protect me from painful memories. This was especially clear when I went through my medical records and got to read nurses’ and doctors’ notes about just how sick I was from their point of view, and when I interviewed my mom and realized how close she thought I was to dying.

LU: One thing that really struck me as I read your book was how it made me reflect on my own experiences and how far I still had to go towards advocating for myself. Even five years after being on the path to diagnosis and treatment for my chronic headaches and pain, I still find myself putting up with bad medical treatment because sometimes it is easier than self-advocacy. Do you think that our abilities to self-advocate are recurrent or always developing?

TM: Always, always developing. It’s hard enough to advocate for yourself when you feel well, and it is incredibly hard when you’re sick and in pain and tired and hopeless. There will be times when you don’t speak up when you’re being treated poorly and you’ll beat yourself up for it later. It’s really difficult to not see the failings of the system as your own personal failings (but I want to remind you that they aren’t. No one teaches you how to be good at being sick!). I try to share as much as I can about what I’ve learned about self-advocacy over a decade of illness, and I do think these skills are important, but I also want to highlight that being ill incurably or long-term also requires community care and community advocacy. I always encourage people to bring a trusted friend or family member or someone from your support group along as a partner-advocate. They can act as a second brain to help you ask questions, take notes, and document any negligent or discriminatory behavior. And chronic illness is fucking lonely! Sometimes having someone else there, just there, makes it all feel a bit easier. Survival is a community event, as Viktor Frankl said.

LU: In several chapters, but especially in “The Brain and the Self,” you discuss how having chronic illness can cause trauma, but can also be compounded by other past traumas. What are things that you are still learning about trauma’s connection to the body?

TM: I’ve barely scratched the surface of what I know about trauma’s connection to the body! Research in this area is just now getting taken seriously (meaning: money is finally getting thrown behind it), so we’re going to learn a lot more in the coming years and that’s exciting for me since so much of my disability justice work focuses on the intersections of physical and mental health.

It’s hard enough to advocate for yourself when you feel well, and it is incredibly hard when you’re sick and in pain and tired and hopeless.

But from a more personal, anecdotal perspective, my own body is always reminding me of past physical and mental traumas; for example, I live with tons of scar tissue in my guts from years of severe flare ups, so even though I’m in remission now thanks to infusions of a biologic medication, the pain from the scar tissue (which causes intestinal narrowing, blockages, and other unpleasant stuff) is a reminder. Physical pain, even when it seems acute, is often a reminder of bigger, more complex traumas for chronically ill people.

Another personal example is a kidney infection I had last December. It kicked off a major medical PTSD response; just the thought of going to the emergency room triggered the worst panic attack and series of medical flashbacks that I’ve had in years. And then that response upset me because I thought I had “gotten over” or “moved past” that sort of severe trauma response, and I felt like all my years of hard work in therapy was for naught! I was thinking about it in very black and white terms when so much of physical and mental health (and the overlap of the two) lives in gray.

I try to think about trauma like I think about grief: it’s going to ebb and flow forever. Forever! As I wrote in the book, my dad has been dead for almost 13 years, and when he first died I spent weeks staring at the ceiling, wondering if I should kill myself to make the pain of losing him go away. As time has gone on, I have some days when I don’t think about him at all, or I latch on to a memory of him and smile or laugh. But every so often it creeps up on me, and thinking about him still hurts so much that I can’t get out of bed. Does that, then, negate all the work I’ve done to carry my grief in a way I can live with? Of course not. Living with any trauma is like that. Some days are going to hurt a lot and some days less. Some days you’ll need to scream and cry and shake your fists at the sky and other days not.

LU: In the book, you address the pandemic, saying “The COVID-19 pandemic revealed all of the cracks in our healthcare and social systems; even the slightest stress resulted in wide-spread failure for the most vulnerable.“

As more people are vaccinated and politicians and individuals declare that the pandemic is “over,” despite all evidence to the contrary, what do you hope that people learn from this experience?

Physical pain, even when it seems acute, is often a reminder of bigger, more complex traumas for chronically ill people.

TM: It was difficult seeing a lot of changes being made by governments and employers because non-disabled people needed them to maintain productivity when chronically ill and disabled people have been demanding these changes for decades (example: remote work on a mass scale). But even those changes are already being rolled back as employers demand a return to the office, and when people are pushing back, they’re being fired instead of granted accommodations. I wish I could say I was surprised, but not even a mass-casualty pandemic can change American capitalism.

LU: You offer as many nuanced resources and research as possible in each chapter and in the footnotes and appendix, but you also acknowledge that this book is ultimately your unique experience that can’t be everything to everyone. What do you hope that chronically ill readers leave this book with?

TM: I hope they feel seen, mostly. I hope they feel less alone, even a little. I hope it helps them wade through the grief and feelings of self-loss. I hope that after reading the book they know that their lives are worth living (maybe even more so!) with chronic illness and disability, even when their governments, cultures, employers, friends, and families make them feel otherwise. I hope they come away knowing that they belong to a community of radically empathetic, helpful people. I hope they understand that it’s okay to be angry, and that their anger can be righteous. I hope it helps them to see joy as a necessary act of survival.

It’s really difficult to not see the failings of the system as your own personal failings, but I want to remind you that they aren’t. No one teaches you how to be good at being sick!

Because I’ve been writing about chronic illness for so many years, I get a lot of emails and DMs from other chronically ill and disabled people as well as their caregivers. A lot of the people who reach out to me are newly diagnosed, and they aren’t sure that their lives are worth living now that they’re sick forever. Some of them have contemplated suicide or self-harm. So when I wrote the book, I was always thinking of them. I needed to give them something that, when they finished it, they felt like they wanted to stick around. I wanted them to know that they are wanted and needed here.

LU: If your book represents one person’s experience, what other books or authors have you read by other chronically-ill and/or disabled writers that you feel might form a canon of sorts for people to learn more about the nuances of living with chronic conditions?

TM: Off the top of my head, here are some that inform my own work that I think everyone should read: