The first chapter of Daniella Mestyanek Young’s memoir Uncultured opens with a screech: It is 1993 and Mestyanek Young—then 5 years old—is inside a commune in Brazil, standing at the back of a line of children waiting to be paddled. As she explains, it’s a normal day in the Children of God, the cult founded by David Berg in 1968 and made notorious from allegations of sexual and physical abuse.

From that unsettling opening, the book follows Mestyanek Young through another decade of growing up in the notorious sex cult, a childhood spent moving from commune to commune while living in the shadow of near-constant physical and sexual abuse disguised as divine love.

At 15, she finally broke free and ran away to Texas, landing a job at Chick-fil-A and enrolling in a Houston high school before going to college and eventually joining the military. But the U.S. Army, it turns out, is grappling with problems not wholly dissimilar from those that plagued the Children of God: violence, misogyny and the constant fear of both. Not just the story of a harrowing upbringing and its aftermath, Uncultured presents itself as an exploration of group behavior, and the ways we are prone to programming and indoctrination.

When Mestyanek Young and I talked about that during a phone call, I reminded myself to make sure to avoid using the word “cult” in the casual ways people often do, as a descriptor for any group with the slightest tendency toward intensity. Saying that to a cult survivor seemed almost rude, an insensitive way of minimizing their pain. But in a book dedicated to exploring the parallels between cults and all other organized group behavior, it’s also kind of the point.

Keri Blakinger: By the end of the book you seem to come to a very cynical conclusion that there’s essentially no big difference between a cult and any other sort of organization with its own culture. Is that what you want readers to take away from this?

Daniella Mestyanek Young: I kind of agree with you that maybe the end is too cynical. But what I want readers to take away is just that when you see something we can all agree is evil—a sex cult that traffics children, except 100,000 people didn’t agree that it was evil—and you see such striking parallels with group behavior and echoes of rape culture in the United States Army, you are then invited to see that in your own life and ask, “Where are the parallels”?

I kind of jokingly say that I want readers to just walk into every group that they’re in and ask themselves: Is this a cult? Just because I do think that the fundamentals of group behavior are the same. I think groups come from a very similar DNA, and I also think that what people want to call good or bad values, for example, are sort of two sides of the same coin. You know, most people would never say love is a bad value, but David Berg weaponized love.

With this move into people-first organizations—which is definitely an improvement on profit-first—I think the potential to go into extremism is right there. We see it in the story of WeWork and the story of LuLaRoe, which are some of the best depictions of being in a cult that I’ve seen. And those are businesses.

KB: Constantly asking that question seems like such a lonely way to approach human interaction.

DMY: I think that for many of us cult babies, we do just fundamentally have a different view of group behavior, and human behavior. We didn’t get to form personal identities, so then you only have group identities. And then you get that taken away, or you learn to live without it. So I do think that for many of us, it’s hard to be in groups.

I study leadership, I study groups. Extensively. But I’m happy that I don’t have to be working at a corporation anymore, because I do think I’m quite cynical in how I look at groups and where the potential for toxicity is.

KB: If one of your takeaways is essentially that there’s no fundamental difference between a cult and any other organization, that seems in tension with the many chapters you spend delving into the abuses and trafficking in the cult and in the Army.

DMY: I guess it’s not that there’s no fundamental difference—it’s just that there’s no obvious and clear differences in the way that people think there are from outside these cults or these high-control groups.

Like I say in the book, people say to me all the time, like, you don’t seem like a cult survivor. I’m like, “Okay, how many cult survivors do you know?” And every documentary you ever see about cults, the only way we can talk about it as cult survivors is sensationalized. But what’s actually creepy about cults is that they’re so normal. Even the children that grew up trafficked in the sex cults can’t all agree that it was a bad thing. And that’s the same thing you see in many organizations.

I don’t know if you’ve ever heard the quote that human beings are all 99% the same, it’s that 1% of difference that causes all the world’s problems. And I feel like with groups, basically they all have 99% of the same DNA and the same potential trouble spots or potential great spots. But what that means is that no matter how great you think your group is, you’re also just 1% away from the sex cult that trafficks children. And even the Children of God didn’t start that way—they started as love, faith and Jesus and they went on a ten-year journey to become one of the most evil organizations.

KB: This book pretty extensively tackles misogyny as one of the prominent themes. Did you think of writing this book as like a feminist act?

There’s so much self-help and thinking about the individual in our individualistic society—but how much do we think about groups?

DMY: 100%. One version of how we thought of telling the story was going to be less focused on groups and much more focused on feminism. I think we ended up sort of blending, going through the process of telling both of those stories we ended up blending it a lot.

But I don’t think I realized how critical it was going to be of the culture in the military. I still saw myself as a proud Army captain. I mean, I didn’t resign my commission until last year. It was really hard for me to move on from being Army captain and understand that while I would hope everyone would agree rape culture is bad in the military, let’s fix it. But of course, I’m going to come under fire for speaking out against my family. So a lot of that was a journey for me and was surprising and the cover was reflective of that.

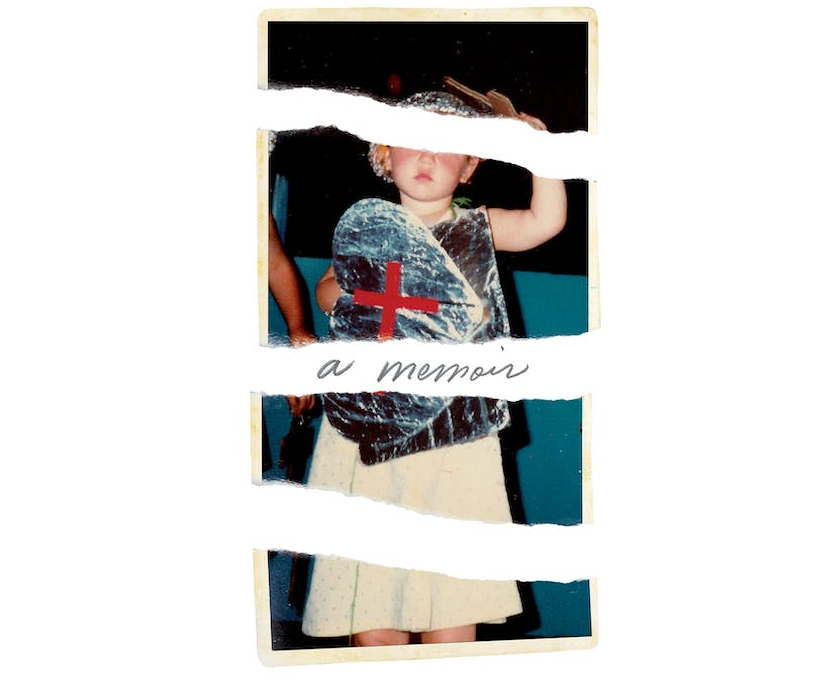

KB: Tell me about that picture of you that’s on the cover.

DMY: That’s me being trafficked as a child by a cult. A little soldier of God.

The cover was sort of the break in the identity for me. Like, “You’re really doing this, you’re really moving on from Daniella Mestyanek, U.S. Army captain, to that girl that wrote a book about cults.” And using this photo for me was hard too because the photo itself felt very exploitative.

All groups have the potential to become toxic, just like all people have the potential to become toxic.

This is me clearly at an age where I couldn’t consent to being filmed for stuff that we were then—all the children of the Children of God—were forced to sell on the streets all over the world. I kind of had this realization that part of the act of me writing this book and of telling this story was me taking back all of these things that happened to me and exploiting my stories for my own benefit and the ideas I want to talk about. So using this picture in a powerful way is kind of doing the same thing.

KB: What has the response been like so far? I’m asking this because I’ve seen some of your back-and-forths on Twitter lately, and I’m wondering how the fact that you are a woman writing about systemic misogyny in male-dominated spaces has influenced the response to this book.

DMY: I’ve gotten a lot of praise, a lot of applause, and a lot of, “You’re so brave.” I’ve also gotten: “Why are you lying about your service? Why are you a traitor? Why do you have to criticize the Army?” And I think I’m allowed to tell both the story of how I’m proud to have been one of the first women being sent out deliberately on those ground patrols and also how they were warning us to watch our backs and be prepared essentially for gang rape. I don’t think anyone wants me to tell those stories, but here we go.

KB: So what do you want people to get out of this book?

DMY: It is definitely a trauma survivor story and a recovery story. I wanted to write a book like the books that have helped me, so every time we vulnerably tell our stories, someone else is going to have these realizations. And I hope my story can be part of some other people’s survival guide. And also I want them thinking more about groups. And to clarify that cynical-ness—it’s not that I think all groups are the same. I just think all groups have the potential to become toxic, just like all people have the potential to become toxic. There’s so much self-help and thinking about the individual in our individualistic society—but how much do we think about groups?

In our society we have all these ways of isolating ourselves into one idea and everything is becoming more and more polarized, so I really do want people to stop and think about their group dynamics. You don’t have to compare it to a cult. I find that makes everyone uncomfortable, no one wants their organization compared to a cult.

At the end of the day, in no way am I saying the U.S. Army is as bad as the Children of God. But I’m saying here are all these exact same sorts of toxic structures that we see in both groups. And where can you look at those and then see those in your groups? And either, you know, help fix it or get out.