On the day that Jimmy arrived, I was convinced that I was going to die. I caught H1NI three days before my thirteenth birthday, and it was early enough in the Swine Flu epidemic that my small-town Ontario doctor hadn’t seen it before and wasn’t sure how to treat it. Stomach bug symptoms came first. Funfetti cake in and Funfetti cake back up and out. Then, my muscles atrophied, locking my arms and legs and jaw in place.

My memories from that time are merely fragments. Hot pink pillows soaked with sweat. Flat ginger ale. Nicolas Cage’s voice as the dad in Astroboy, playing from down the hall. A bedroom door on the bottom floor of a green and white Duplex. A fist-sized hole in its center.

I have no way of explaining the exact moment in which I split. There is simply a before: immobile and afraid. And an after: a new voice inside my head. Not my own. Someone else.

You’re okay.

I felt faint, like floating, like falling, and I could see myself, my body, separate from where I was, in front of me, like a video game, and I wasn’t afraid, and I wasn’t in pain.

I had been writing little stories and poems for years beforehand. I thought I knew how to create characters.

A week later, I was allowed back at school. I had missed a provincial literacy test while I was ill, so my eighth-grade teacher assigned me a short story project to write in its place.

I had been writing little stories and poems for years beforehand. I thought I knew how to create characters. Describe settings. Craft dramatic and angsty thirteen-year-old sentences. At the very least, I knew what it was like to consciously create something from nothing.

But when I sat at the desktop computer in my bedroom, equipped only with Open Office, Microsoft Paint, and minesweeper, I felt a tug on my brain—physically, like the light-headed sensation that follows whiplash.

And I heard the voice again. And instead of pushing it back, and creating new words, I listened.

Dissociative Identity Disorder is one of several dissociative disorders officially classified in the DSM-5. Formally known as Multiple Personality Disorder, DID’s diagnostic criteria are as follows:

A. Disruption of identity characterized by two or more distinct personality states, marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency, accompanied by related alterations in affect, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, cognition, and/or sensory-motor functioning.

B. Recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.

C. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

I didn’t know about dissociative identity disorder at thirteen, but I was old enough to know that something was wrong with me.

Dissociative Identity Disorder can only develop after overwhelming experiences, traumatic events, and/or abuse occurring in childhood in a person whose brain is more susceptible to dissociation: a mental process of disconnecting from one’s thoughts, feelings, memories or sense of identity.

Most psychologists agree that DID only develops when these overwhelming experiences or traumatic events are consistent, paired with disorganized attachments to primary caregivers, and take place before the ages of 5-9 years of age. However, traumatic events after the age of nine can trigger the splitting off of additional alternate states of being, or alters. When someone with DID is traumatized, their brain essentially creates a new person to hold the memory of that trauma, to hide it from the person who is conscious in the body the most, or the host.

Unlike its portrayal in movies like Split, DID is typically a covert illness, created so that the host and the people around them are unaware of the traumatic events that certain alters experienced for them.

Because of this, DID is often diagnosed later in life. You’ve likely met someone with DID and had no idea.

If you’ve met me, either as a friend, a co-worker, or the author of The Pump, then this is a certainty.

By 2021, I was an entirely different person—not just by growth, but by fusion. I had personality traits and memories that I didn’t have in 2017.

I was first diagnosed with a dissociative disorder in early 2019, and my first fiction book was published in Fall 2021. I mention these two facts together because, though being a writer and being a DID system are different aspects of who I am, I will never be able to separate them.

Long before I was an author, I was still a writer; long before I had a DID diagnosis, I still had to manage the symptoms of DID and its complex post-traumatic comorbidities.

When I first became aware of Jimmy, I didn’t know that I had dissociative identity disorder. All I knew was that he wasn’t a character I had consciously created.

Jimmy has a voice that is distinctly not my own. Internal—never from an external source. There were other voices before him. Stephen. Claire. Each distinctly their own. When I was younger, I thought that they might be guardian angels. I didn’t know about dissociative identity disorder at thirteen, but I was old enough to know that something was wrong with me.

I kept Jimmy to myself, but I wrote about him. Thousands and thousands of pages that I will never share. He spoke. I wrote. And we processed his existence together.

After I wrote about Jimmy, I wrote about the other voices as well. There was a difference between writing fiction and writing about the people in my head: fiction required creation—this was listening.

Imagine writing while handcuffed to someone—someone who you’ve been handcuffed to for most of your life, who knows you more intimately than anyone else. Imagine that, while you write, they tell you about themselves. You copy down what you hear. You try to understand things about them—things that are really about you. Memories. Preferences. Motivations. When I write fiction, I’m creating all these things from scratch. When I’m listening to an alter, trying to understand who they are, I’m not creating anything at all. Slowly, year by year, word by word, I learn how to communicate with who I’m writing about.

I can connect with a fictional character I’ve created on an empathetic level, but when I am done writing, I can disconnect from them as well. I can’t disconnect from my alters. I can’t change things about them to make them more interesting, or change their backstories, or cut them out of the narrative of my life altogether. Each alter exists for a specific purpose related to my life experiences, and all of them exist to keep me alive.

Communication within my system continues to take a tremendous amount of effort. I have some alters who I have no communication with. When they switch out, I have no awareness, and when I’m back, I don’t remember anything they’ve experienced. I only came to learn about these alters because one of them started leaving me notes. Sometimes just reminders of things like where I was or what I had been doing; sometimes long paragraphs about the trauma they had experienced.

When I was finally diagnosed, it became clear to me that communication between me and the rest of my system was necessary for living a functional life.

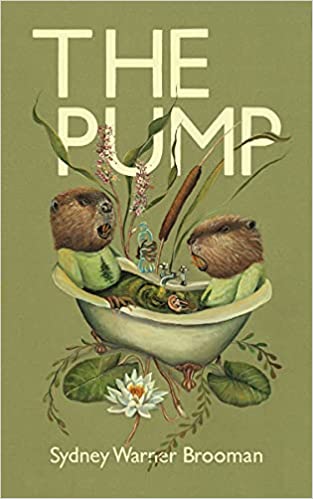

My short story collection The Pump was a way for me to process my childhood and adolescence growing up in Grimsby, Ontario: the isolation of being queer and living below the poverty line; the hypocrisy of municipal governments advertising our area as the Greenbelt while polluting the land; the strangeness of leaving the place I grew up in and returning a completely different person.

Writing the book was an incredibly cathartic experience, but in 2020 and 2021, my dissociative disorder made editing it one of the most difficult things I’ve ever done.

My personal healing trajectory includes something called fusion: when two or more alters fuse together and become a single alter through increased communication or healing. I wrote the first draft of The Pump in 2017, but by 2021, I was an entirely different person—not just by growth, but by fusion. I had personality traits and memories that I didn’t have in 2017. Editing my work included having to write new sentences, and in some cases, entirely new chapters, in the exact same style. This was close to impossible because I was—quite literally—a different person.

Editing The Pump was also difficult because it required me to read and reread descriptions of the town that I grew up in. This process was incredibly triggering for me, often inducing flashbacks, and worsening dissociative symptoms. For other alters that held different trauma than I did, rereading the book was impossible. I had to go slowly, carefully, and communicate well enough to ensure that certain alters were farther back in my mind.

Writing my newest book involved a lot of note writing: both notes for myself, from myself so that I didn’t forget my ideas, and notes from me to any alter who might switch out, to help them understand what I was doing.

Better communication between alters can sometimes increase something called co-consciousness: when two or more alters share consciousness—the front of the body—at the same time. Think of it like a race where two runners have one of their legs tied together, and they must learn how to walk as one person, rather than two separate people.

Through writing, I’ve managed to connect to my alters, facilitating empathy and understanding.

Two of my alters—Jimmy and Stephen—have learned throughout my life how to act exactly like me, how to communicate with me when they’re out and I’m not, and how to continue writing something that I started. But there are other alters in my system who have no ability to mask. They can’t act like me, let alone write like me. When those alters are more active, or ‘closer’ to the front of my mind, I can’t write at all.

I wrote this piece with Jimmy close by. Most of my DID involves something called passive influence, where an alter’s memories, emotions, or thoughts can influence whoever is fronting in the body. I can identify when certain emotional reactions or memories are not my own, but I will get hints of them in my awareness regardless, like drinking vitamin water that tastes faintly of fruit, almost as if the flavour is far away.

Jimmy remembered more of my thirteenth birthday than I did. I often had to pause my writing and battle intense dissociation. Eat. Rest. I cannot force my brain through work that could force it to split. We reorganized my desk in a state of wavering co-consciousness. I had a flashback. Fought my telltale signs of an appending switch: headache; nausea; dizziness; vertigo; blurred vision; confusion. Switched anyway. Sat in the driver’s seat of the car of my body while Jimmy took a bath. I consider this a good writing day. We did what we could.

Through writing, I’ve managed to connect to my alters, facilitating empathy and understanding. Privately, in the comfort of my own home, writing about my system has been a practice of healing.

Writing may not be your healing practice. You might find solace in singing, or cooking, or simply giving yourself the time and space in a safe place to listen to the parts of you that need to be heard—regardless of whether you have DID. Whatever your practice is, hold onto it. In her new book Body Work: The Radical Power Of Personal Narrative, Melissa Febos says “There is no pain in my life that has not been given value by the alchemy of creative attention.” You do not need to suffer for your art—to choose between your creativity and your healing. Search for the place where the two of them meet. I can’t promise you that you’ll find it. But the act of searching will change everything.