“Have you heard of loneliness before?” writes Charlee Dyroff. In the not too distant future, New York City will be remembered the ancient city that once served as the “epicenter of narrative, of creation.” Loneliness as a word or concept will be mostly forgotten. Dating apps will still be a thing.

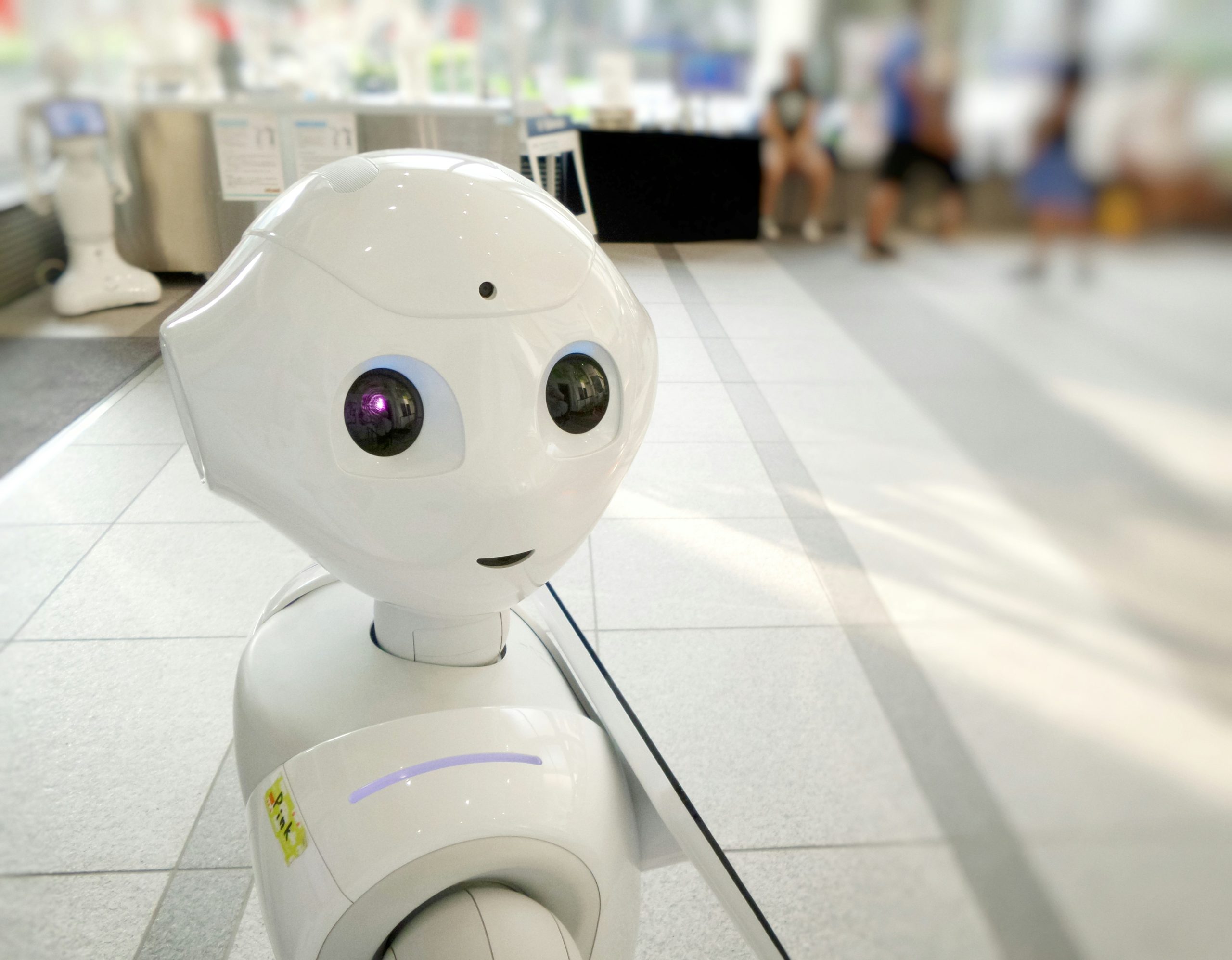

In Loneliness & Company, Lee, a promising graduate of the Program, an institution where “everything ran seamlessly without calling attention to itself,” has just been hired as a Humanity Consultant. She landed a job at a company training Vicky, an advanced AI, about friendship and empathy. But soon enough, the company’s secret mission quickly emerges: to solve loneliness. Lee, who hasn’t quite felt loneliness before but who is driven by ambition and determined to prove herself, begins earnestly to research people, friendship, love. She studies her roommate Veronika and a group of girls she calls BABES, envious of how effortless their exchanges are, allowing their algorithm to shape her. On a date, which she considers field study, she tries to be the person the BABES would fawn over. All the while, she recognizes that she is too often “the common denominator in misunderstandings,” that she, too, suffers from the human need to feel special.

Lee tries to dismantle human behavior so that she might better understand it—so she might more fully become it. Common experiences, from orgasms to friendships to nude modeling, are deconstructed so that connections between people might be better rebuilt. Dyroff, taking a page from writers like Molly McGhee and Jessamine Chan, slyly critiques social structures like dating apps, community housing, social media personas, careers, capitalism. A fast paced anthropological mystery anthropological, Loneliness & Company reminds us how even our wounds—especially ones like loneliness—are what make us human.

Annie Liontas: What does it mean to write a book about loneliness in 2024? How lonely are we?

Charlee Dyroff: This is an interesting question because loneliness has definitely been in the news more thanks, in part, to the Surgeon General’s honest op-ed in the NYT. Ever since my book came out, friends and family have been sending me articles about loneliness in schools, in workplaces, etc. In the world of Loneliness & Company, which is set in a near future, there are a lot of lonely people.

But in a way, it’s completely random that Loneliness & Company published during a time when people are open to thinking about and engaging with the topic. As you know from your own publishing career, authors don’t often have much control on when the book comes out. All we can do is pour our heart into writing it and then see what happens. I started drafting this manuscript years ago back in 2019—before the pandemic first called more attention to the unbearable sadness some kinds of isolation can cause. In some ways, writing this book was a way for me to break through my own loneliness. Ultimately, it’s a story of hope.

AL: I absolutely empathize with the need to seek out art as a way to grapple with existential isolation. You mentioned that writing is a way to break through your own loneliness. How so?

CD: I think writing can be a way of reaching out, even if we write things that we don’t expect anyone to see. It’s a way to communicate something we might not be able to otherwise… to ourselves, to strangers.

Writing this book was a way for me to break through my own loneliness. Ultimately, it’s a story of hope.

This manuscript went through so many iterations and in the first one, loneliness wasn’t a theme or part of the plot at all. A nonfiction professor of mine actually pointed out that my essays had an air of isolation, and that was really the first time I admitted to myself that I felt lonely. And it felt so shameful at the time. And of course, when I went to edit the manuscript, the questions I had about loneliness were already there, hidden in the text. So I think writing through them helped me quite a bit.

AL: Isn’t it astounding when people see traces of us in our work that we don’t even see ourselves? This is resonant with Lee, your main character, who at a certain point in the narrative becomes a subject of study for the reader. We see things about Lee that she remains blind to even as excels in certain areas of her life, and in her breakthroughs with her research with Vicky. How is Lee both part of and apart from the people in her world?

CD: Yes! Totally. You’re absolutely right about Lee. As readers, we see her blind spots, especially early on. Lee’s an interesting character to follow because she grew up in this near-future society that prides itself on efficiency. She trained in a rigorous, success-oriented research program with uniforms and schedules—and she really thrived in that sort of disciplinary environment.

Because of this, when we meet her she has a lot of drive and ambition, but is quite ignorant of anything outside of the Program. It was interesting to write a character who was so externally motivated that they almost didn’t know what they themselves wanted?

Anyway, in the book, she’s thrown into a role where she’s tasked with collecting research about humanity to help teach an AI. And because she has this almost debilitating desire to be successful, she forces herself to venture out into the world for more and more information about it… and in a lot of these situations, like when she goes to an old-school diner for the first time, we see her in the world, but how far she’s really removed from it. (Which, I think that feeling—not always knowing what to say or do, but desperately wanting to say the right thing—is actually a pretty human thing.)

AL: We see that elsewhere for Lee, too, specifically as she navigates cultural norms of dating and attraction. As the story unfolds, Lee begins to build a relationship with Chris, someone at her workplace she has met only over a messaging platform and, G, a man she met at a coffee shop and becomes involved with. What did introducing these two very different attractions do for the story, and for Lee’s character?

CD: I can’t remember who told me this, or if maybe I just overheard it at an author talk/reading, but someone once gave the advice that the best way to get to know your characters is to put them in a situation with others and see what they do… It’s a funny thing that’s always stuck in my mind.

The best way to get to know your characters is to put them in a situation with others and see what they do.

Though Chris (her quirky, nerdy boss) and G. (an attractive business man) are very different, they both help Lee learn more about herself through their interactions. For example, they both teach her about intimacy and desire… for Chris, the intimacy of being able to talk to someone, to feel like you can tell them anything. And for G., a more physical kind. But in the end, they both force her to think differently about herself, about the world, about everything she’s been taught.

AL: Much of this book is a study of human behavior—how we build friendships, how we mimic the behaviors of others, how we interpret gestures that are meaningful only because of their cultural significance. What kinds of human phenomena and tendencies drew your attention as you were writing this book?

CD: I was definitely drawn to the ways people interact with each other online and in the world, especially friends. I think sometimes friendship is almost a secret language. Or, even outside of friendship, I was interested in moments of unexpected intimacy or connection between strangers, like a brief conversation at a party with someone you’ll never meet again or when a barista or server knows your order.

Even though Loneliness & Company touches on ideas about technology and loneliness, it’s ultimately a human story full of humor and empathy, and I hope readers find something for themselves in it.

AL: Will the future be lonely?

CD: I don’t think our future has to be lonely. I hope no matter what we find ways to connect and be there for each other.

It seems that oftentimes a novel stems from questions—If we can’t name an emotion, can we still feel it? Does ambition make one isolated? How do we build human-like tech if we aren’t sure what it means to be human ourselves?—and not all of them are answered through writing a book. I just hope that even the act of reading, whether this book or others, is a way that we stay connected over time.

Read the original article here