For generations, in forms both practical and supernatural, the Haddesley family’s existence has been inseparable from the cranberry bog. Family lore has long led to a belief that their stewardship –– and their sacrifice of their patriarch to the bog –– yields a bog-wife who then marries and bears children for the patriarchal successor.

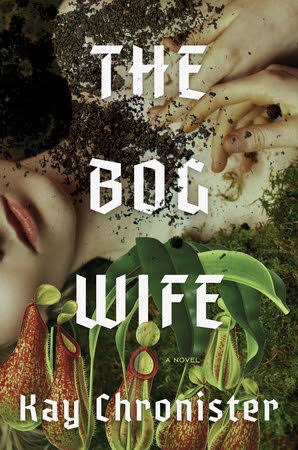

However, at the start of Kay Chronister’s The Bog Wife, the titular character fails to materialize after the reining Haddesley father is sacrificed, leaving the five remaining Haddesley siblings to navigate life without the rituals that have sustained them for all of history. As the reality of their lives begins to bend away from the stories they have long held as fact, the siblings must make decisions about their relationships to one another, the land, and the truth of their family history.

The author of Thin Places and Desert Creatures, Chronister brings a deeply Gothic sensibility to her latest novel. Riveting, deeply eerie, and lushly atmospheric all at once, Chronister’s novel offers a spellbinding rumination on a variety of tangled ecosystems. Through deeply considered characters, a nuanced, specific portrayal of the bog, and supernatural elements that reveal our deepest human impulses, Chronister invites readers to contemplate the ways in which the systems and histories we are part of can both hold us and be deeply harmful, all at once.

I had the opportunity to speak with Chronister over Zoom about succession, environmental stewardship, the harms created by patriarchal systems, and the way stories can be used to obfuscate difficult truths.

Jacqueline Alnes: I had a dream (nightmare?) about a bog when I was in the middle of this novel, which seems like a testament to how much this particular environment seeped into my consciousness. It made me think about how much you probably were immersed in this landscape while writing. What drew you to bogs?

Kay Chronister: When I started writing The Bog Wife, I was still living in Arizona, which is about the least boggy landscape you could exist in. I knew I wanted to write an American Gothic novel and I felt like I wanted it to be really grounded in a sense of place, as well as ecology and culture. I was thinking about a few different kinds of wetland environments and I ended up getting really interested in bogs because they tend to be less hospitable to life than other wetlands and they have some unusual ecological features that ended up working well on a symbolic level for me.

I didn’t actually get out to see the kind of bog I was writing about until several months into the novel. I’m very glad I went. Being able to smell it and touch it and experience it and be there was really useful. I was deeply absorbed in bogs and bog facts for a long time.

JA: What’s the wildest fact you came across?

Bogs are different than other ecosystems in that they have this rhythm in this process of succession, which seems to work best when they are almost benignly neglected.

KC: The thing that surprised me most to learn about bogs is that most ecologists consider them to be intrinsically transitional ecosystems. Usually, a place is not a bog forever. When I started the novel, I thought this was going to be a book about climate change, in some sense, or ecological decay, and I kept being resisted in writing that plot by the facts of bog ecology. When I realized it was a transitional landscape—change is what it does—that really altered the trajectory of the book. They are really resilient, because they are supposed to change and evolve.

JA: In the book, the bog feels difficult to pin down. It felt peaceful and violent all at once, like it could preserve a body, which seems like a kind of embalming, but has elements of potential harm inherent as well. I felt like I could never really get grounded in the bog because it felt so alive and still at the same time, if that makes sense.

KC: I was struck by that when I visited a couple different peat bogs—both of them struck me that way. From the surface, if you don’t understand what you’re looking at, it doesn’t look like much is going on. So much of their activity and what they are doing is invisible, under the surface. Understanding what you’re looking at requires context or experiential touching and feeling, which is discouraged because that kind of interaction harms the bogs.

JA: Which aligns so well with how the Haddesley family views “their” bog. They believe they have this claim over it, which opens this thread of humans believing they have power over land or are “stewards of the land.” In the case of the Haddesley’s, it becomes interesting to wonder whether they are protecting the bog from invasive species or are they themselves an invasive species.

KC: I really wrestled with the question of whether bogs need stewards, need human interaction generally, as well as in the particular case of this family who really aren’t doing a great job of stewardship. In some cases, they do. In Cranberry Glades, West Virginia, they’re doing a lot to keep invasive species out of the area to avoid them outcompeting the native plants. Bogs are different than other ecosystems in that they have this rhythm to them in this process of succession, which seems to work best when they are almost benignly neglected. That might be true for a lot of ecosystems, that benign neglect would be the ideal situation for them. What’s difficult is that as human beings we have to use land for things like agriculture and to live on, so then the question becomes if benign neglect isn’t on the table, then what is the best we can do? When our obligations to ourselves as humans and society come into conflict with what would be best for an ecosystem, what do we prioritize?

JA: I can’t not bring up the Bog Wife. For generations, this family has believed that a woman would come out of the bog for the eldest son to take as his wife. I love the way you describe the Bog Wife in the novel as being of the earth, even smelling of the earth. What did you think about while writing this character, especially since she is of this other powerful character in the book, the bog itself?

KC: The mythology of the bog wife began with other stories about nonhuman women who marry into human families, like selkies. There is Welsh folklore of a woman made out of flowers who is brought to life. Thinking about those stories, what I find fun is that there is a certain amount of ambiguity as to how human this woman appears and how human she really is, and how much the husband in question is willfully deluding himself about having some kind of quasi-human marriage partner. I went back and forth about how much to physically describe the bog wife and how much to describe the logistics of this dirt and plant woman who had raised five children and lived in a house and seemed to exist like a human for a while. I ultimately decided, which is pretty habitual for me, that I don’t care very much about the logistics. I wanted her to be in a state of flux. She is more human for a period of time and then less.

JA: Part of her character is interesting because it seems like she has some kind of pervasive sadness that interrupts her life. I started thinking about that and ecological grief and the parallels between how much she wants to be there and how much the bog really wants anyone around. This relationship between place, this specific ecological feature, and other humans is so complicated.

KC: One of the areas I really wanted to leave a certain amount of ambiguity was whether she ever enjoyed or embraced or felt comfortable in her role as mother and wife. We don’t get very much access to her perspective and her children experience her in such different ways that you’re left unsure about what exactly is wrong with her during that period of sadness and to what extent there was any amount of love or happiness there. Thinking about her in the context of selkie stories and other non-human wives, I think they are often symbolic representations of women who are oppressed and who don’t have very much of a voice. They are often fitted into this role of wife and mother without being consulted or having a lot of agency. In a certain sense, that is what you think might be going on with her, but there is also a sense in which she is made out of dirt and plants and she wants to return to dirt and plants.

JA: Speaking of having little choice, I’m thinking about the Haddesley children, who have not grown up venturing beyond the property line. Wenna, the sister who does, is almost thought of as two Wennas after she returns -– the Wenna out there and the Wenna within. The way the Haddesley siblings are isolated means they cannot access medicine, traditional schooling, people outside their family, histories outside their own, etc. What did you learn from writing about this particular kind of isolation, especially in regard to place?

KC: When I started the novel, I was thinking a lot about how I wanted to represent the family’s isolation. I knew in some sense it was going to be deeply harmful to them, for the obvious reasons you mention, but I didn’t want it to be a totally bleak picture either. I wanted them to feel, whether it’s true or not, that there is something unique and enjoyable and comfortable and safe about the fact that they have grown up in this tiny family culture, isolated from everyone else. Holding those two things together from the perspective of the siblings, it was interesting to play with that and think about the things they’re missing that they don’t even know they are missing and the things they think they have gained, that from an outsider’s perspective you might think are not so great.

Selkies and other non-human wives are often fitted into this role of wife and mother without being consulted or having a lot of agency.

I read a lot about fundamentalist families and families involved in fringe religious movements who live in isolation and it was really useful in thinking about how complex that experience can be and that retrospectively, for children who grow up and leave, there is this comfort in family culture that is really hard for an outsider to understand.

JA: I love that you make it clear how difficult leaving can be, whether it’s a codependent relationship, a place, isolation, a past self you’re trying to leave behind. I thought you captured so well how humans want to find light in things, even when there is so much dark in a situation.

KC: The core of this book, for me, was exploring a family system that is deeply dysfunctional and deeply unhealthy in some ways, but also has its own equilibrium or momentum. I’m interested in the ways that family systems work together and, within that, how much people can slowly accommodate without realizing what they are accommodating. When you are writing about a family with history and heritage and legacy on their shoulders, you can see this slow, gradual slide, not just over a lifetime, but over generations, of people accepting something as normal that, from the outside, we cannot fathom thinking about as normal.

JA: Succession comes up several times throughout the novel. There is a belief in lineage. At a certain point, I don’t know if it’s knowledge, age, or the events at the beginning of the book, but something breaks and so the characters are forced to question whether or not they want to perpetuate the cycle that’s been happening for years. Is that something to take pride in or is it not?

KC: The characters in the novel find not having a template terrifying, even if the template is deeply uncomfortable for them. They would rather have a template than have to create something new.

JA: I was thinking about that while reading the rituals. On some level, the rituals feel supernatural (you know, is a woman really going to emerge from the bog?) but on another, they feel deeply human. We all have those rituals that we try to cling to in an attempt to prove to ourselves that we are normal and our families are okay.

KC: The bog, for the family, functions almost as this feedback system. More broadly, supernatural elements in the book serve as externalization of the family’s drama. The bog itself is an externalization of the family, or they experience it that way. The supernatural elements, for me, are an amplifier. They make it feel bigger and more heightened but really, the story is about these human elements and how each of the siblings is experiencing their family changing.

JA: Thinking about the way the Haddesley children were taught the history of themselves, I won’t spoil any plot points, but their isolation means that the family narrative impressed upon them is difficult to wriggle free from, even after their patriarch dies. It made me think about how stories can be a cushion from the hard truths we don’t really want to know about ourselves or our lineage or our parents’ pasts. What did you think about story while crafting this one?

Rituals are a way of imposing a narrative on a transition or a change or on something that threatens to be chaotic on its own.

KC: I studied British history and I was thinking about these narratives that people use to manage their sense of themselves or their families, or even their countries, and the extent to which these narratives are not really at all about what happened, but about meeting emotional needs. So often, that’s how memory works. We take experience and we create narratives from it. That is amplified for this family because their experience of the world is so tightly controlled by narrative. Even the interactions of these siblings with the bog are always preemptively framed by these narratives they have been told all of their lives, so they almost don’t get to have individual, first-person experience of it. It’s already been filtered. Rituals are like that. Rituals are a way of imposing a narrative on a transition or a change or on something that threatens to be chaotic on its own. Thinking about how important narrative is in this family, it was fun to build in lots of different ways that these narratives are introduced into their lives—there are the oil paintings, the memoirs, the rituals, the verbal stories. It was very important to me that we eventually get not just a debunking of an old narrative, but that we have access to new narratives at the end. It’s hard for us to experience things without some form of narratives, I think.

JA: We have to talk about the patriarchal structure of this family, right?

KC: Those extremely patriarchal, extremely gendered family structures played into the way I organize the family in this novel. I was thinking about royal succession and this family viewing themselves as kind of a royal family. To them, the word “patriarch” has no negative connotation, right? It’s simply a role that the oldest son takes on, it’s not objectionable. What made it more complicated for me, as I was building this family system where there seems to be a patriarch and he seems to have absolute control and the sole right to carry on the line, is that he is in a very vulnerable position, given the way this family cycle works. Eventually, he will be sacrificed for the good of the family. He is also the only one who has to enter an uncomfortable and unwelcome intimacy with the land. There are certain trade-offs to this family.

I thought a lot about royal succession and kingship, too. I was finishing a dissertation about British history while I started this novel and one of the things I was reading quite a lot of was 17th and 18th century press about the Kings. There is so much almost tabloid attention given to their bodies and their reproductive systems—and for Queens, too, of course—and whether or not they are going to be able to produce an heir. It’s an extremely intrusive, public claim on their bodies that exists in this weird, uncomfortable combination with the fact that they have an immense amount of power over other people.

JA: It’s an immense amount of pressure. As an outsider, it’s sad to witness the ways in which that power can stifle someone’s life who otherwise might be a fully self-aware person who might be able to be more than they could in this role.

KC: It’s probably trite at this point to say that the patriarchy hurts men too, but that’s very much a part of the drama of this family and the tragedy of the family in this novel. As much as being a patriarch is as much an artificial role you’re forced to take as being a wife or being a sister and not being allowed to take on any power.

JA: After spending so much time in this geography, in this place, with these characters, what will stay with you?

KC: Normally when I write something, I don’t feel very attached to the characters or the world. I feel ready to move on once I’m done. What surprised me about this book is how much I felt attached to the characters and how much I loved living in this weird, insular world with them. As we’ve been discussing, in a lot of ways, their family is wildly dysfunctional, but there is this strange, enticing coziness to their life that I almost was enticed by while I was writing it. It was hard to pull myself out of at the end.

JA: Maybe that’s why I’m dreaming about it.

Read the original article here