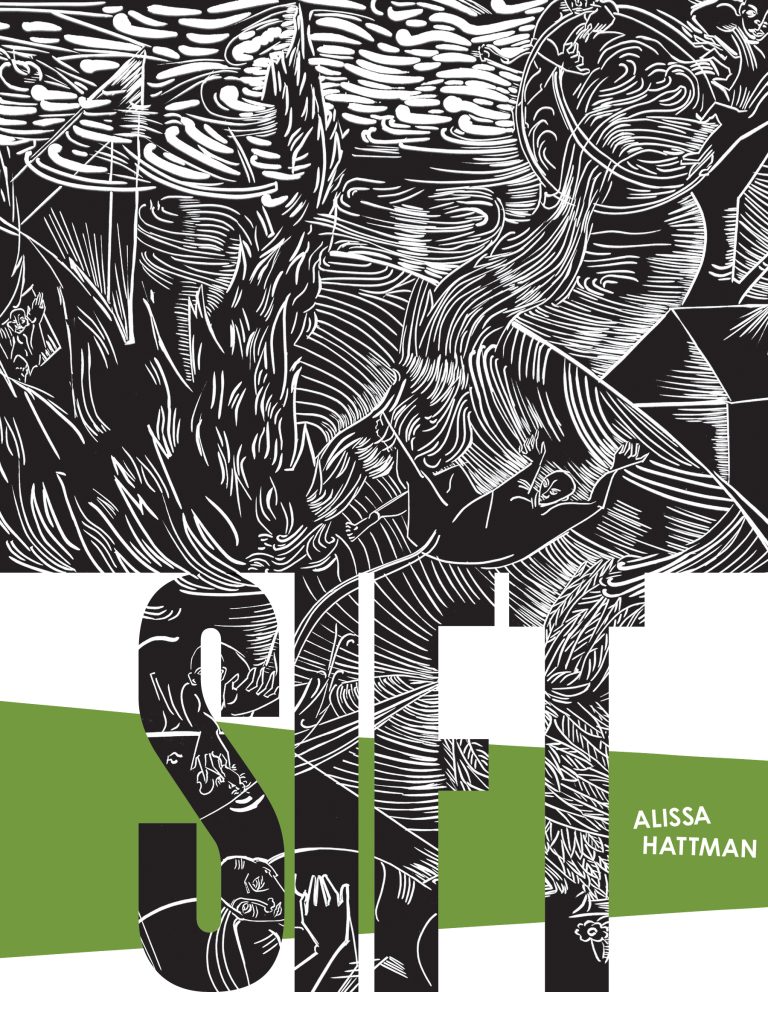

In Alissa Hattman’s debut novel Sift, the world, at first, appears hostile to life, nearly uninhabitable. Skies darken with toxins and smoke. Food, especially produce, is scarce. Drinking water is limited, a result of rivers and other natural bodies that have been poisoned. Fires rage and a tenor of violence hums at the edges of the story.

From this bleak landscape comes a story that unfurls like a new frond: green, bright, and tender. In the opening pages, the narrator, yet unnamed, is picked up by a woman she describes as “the only person I’d met who had learned how to keep living.” As the two travel across a dying landscape in the hope of finding some tangible relief, they begin to better understand not only one another, but themselves, the world around them, and the larger web of history that they are a part of.

Hattman’s prose is lyric, brimming with the pleasing sounds of a poem, and the novel is told in a series of sharp, sparse vignettes that feature not only the human perspectives of the narrator and her newfound travel companion, The Driver, but also includes segments exclusively focused on pond snails, the western banded gecko, wild mustard, and more. Reading Sift encouraged me to think about what it means to listen to the narratives of flora, fauna, and other elements in our world, and just how possible it is to translate that into language; what it means to care for another being or entity, and the cost that sometimes comes with our attempts to care; and how to grieve while also holding on to hope. I had the opportunity to speak with Hattman about all of this, and more, via Zoom.

Jacqueline Alnes: Your book opens with a quote from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Gathering Moss, in which she writes: “From Tetraphis, I began to understand how to learn differently, to let the mosses tell their story, rather than wring it from them.”

I love the way that your book is a human story but also includes lyric sections that are focused on elements in the natural world. What does it look like when we let the environment speak to us rather than us imposing a story on it?

Alissa Hattman: With that epigraph, I was trying to be intentional in this process of gesturing toward the stories outside the human-driven story of the two main characters. I wanted to include more of the environmental elements within their own stories. It can be a hard thing to do because you don’t want to talk for the non-human other, but I approached it as a deep listening. I tried to remove any of the pronouns and any of this sense of subject or agency and see what could surface from that.

JA: In terms of that deep listening, this story seems to be so much about bearing witness: to environmental collapse, and to moments of joy—which aren’t very frequent in this story. You write, “Observing is one way to go on” and “I knew the act of writing would help it stay in my head.” There’s this recurring theme of wanting to remember. For you, does this book represent the importance of all of us bearing witness to what is currently going on in our world or the idea of putting that into language?

Storyteling helps us emotionally to engage with this very difficult topic of climate change or systemic racism.

AH: I do think this deep attention and witnessing can be a type of understanding, and then maybe also resistance in some cases. Paying attention to the environment, the long history of the land, another person’s grief, all of this is a type of repair, a type of listening that I think is very important. Grieving humanity or some of what we’ve lost, like species or the degradation of the land, is a larger witnessing. It can lead to action as well. If there is that type of listening that becomes more relational and becomes more understanding of a larger history, then I think it moves people to change and to act.

JA: It reminded me a little of when Trump was elected and people were keeping track of his tweets. It felt like something to do. It felt powerful at first but then, as it went on, it felt like an insurmountable wall of horrors. In your novel, there is this accumulation of grief—for humans, for air, for water, the internal landscapes of the characters. Did writing during a time of collective grief and unrest inform how you approached this subject?

AH: I started writing Sift at the beginning of the pandemic. It began with a deep fear of loss, which was something that was individual, this fear of losing loved ones, at first, but then it became so much larger. It became an anticipatory grief, of realizing how large and overwhelming it would get. There was so much happening alongside the pandemic. The pandemic is related to climate change. In Oregon, we had fires and then ice storms, increased air pollution, poverty, displacement, environmental racism, redlining, all these things were happening and coming to a head. The larger loss was an environmental grieving, grieving not only this moment but what came before as well.

In terms of what that means for Sift, I knew that I was going to write something that was going to encompass this heavy material, these traumatic moments. I wanted it to be in a way that felt the narrative was calm and safe as well, so there was a sense of yes, this is all happening, and we have community and connection, even if that connection is only one other person or even if that connection is with some aspect of the environment. It was originally just something I felt like I needed to write in this moment to go on but I was thinking about how to create a work that allows us to enter into that space that so many people feel overwhelmed by. I don’t know if it succeeds, but that was the plan when I started. I wanted to thread in love, community, friendship, and a certain amount of safety.

JA: While reading, I got this sense of interconnectedness, which is so beautiful but also means that when one thing starts to falter, everything does. It’s hard to reckon at any moment with how connected we are to the environment and other people.

AH: This quote from Hannah Arendt, “Storytelling reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it,” gets at this idea of being able to place a lot of these intersections together into story and some meaning will come of it. This is one of the great tools that we have as storytellers and novelists, to express a moment in some amount of clarity so that a number of people can take away intersections from that moment, something that will be meaningful to them. Storytelling is a place where repair can happen.

I think about holding some of those histories, social and environmental collapse, as being a rupture; holding and witnessing and discussing outside of the story is a type of repair. Not in a sense that it will fix everything, but that it emotionally helps us to engage with this very difficult topic of climate change or systemic racism. I think about how story is many-faceted in that way. Even though it might not change hearts and minds, there is a potential for something larger in that conversation in talking about literature or writing.

JA: In Sift, you write, “I did not care for you as I should have because I did not know, or I did not take the time to learn what caring for you meant…I am sorry for every casual or not-so-casual way I harmed you.” Care and harm seem like flipsides of each other in that none of us are perfect in our attempts to care for another person, being, or the space we are in; it’s an imperfect practice. Did you start to develop a semblance of what care might look like in our present world?

AH: The passage that you read is recognizing that there are things we will do that can hurt and can harm. There is no perfect way of caretaking. I’m not a parent, but I talk to people who are parents and they will say that one of the early lessons they have is that there is no perfect way of doing this. They are going to make mistakes and it’s going to be hard. There is going to be some harm, no matter what. I think about that in terms of any relationship, really. So you try to do what you can so you cause the least amount of harm or, if you do cause harm, to spend time repairing.

In this book, there is what’s held and what’s let go. The characters keep passing back these stones, these stories, back and forth. There are certain times when the other person can hold it and certain times when they can’t. It’s difficult to be able to recognize that and also communicate that, on the small and large level, too. When we talk about ecological grief, which is a term that’s been around since the 1940s, we are talking about the pain that is caused by environmental loss. In 2020, there was a survey that showed two-thirds of adults experience eco-anxiety. Allowing more of this discussion around some of the grief and the fears and the loss of environment is a step toward understanding, witnessing, and action and change.

In the same way we think about grief with individuals or about these different topics with our loved ones, I think about it as trying to hold some of it when you can and recognizing when it is not something you can hold or when it’s something you need to let go of. It would be so interesting to see more environmental grief groups or something like that in the world.

JA: The book highlights that there are these tangible forms of care, or attempts to pre-empt someone’s comfort through blankets or canned food, but then so much of care seems so intangible, which is maybe where some of the anxiety in regard to the environment comes from. I care, but I’m flailing. What can I physically, personally do about this thing that feels so far beyond the limits of my daily existence?

AH: That idea of tangibility and what can be done on a day-to-day basis is something I think about a lot in my life. In the book there’s this one scene where they come across a bag of garbage and I think it’s a very human problem where it’s like, what do we do with all this garbage? In the book, seeing garbage is a moment of hope: maybe there are other people. The characters have this conversation about what to do with it. One character wants to take it with them, but they have to travel light. The other character is being very practical and says no, somebody might come and it might be theirs. She thinks it might be someone else’s treasure. The narrator just takes one bottle from the garbage because she thinks it might be useful.

When I have felt joy in life, it’s because I have recognized my mortality or the mortality of others.

The thought process of going through recycling or being a conscious consumer is something that happens every day. There are these practical everyday things that you do not because you think about what it might mean long-term, but because this is what we do, right now, to care for each other. I think that it’s somehow trying to do the tangible but not being too overwhelmed by the intangible. You’re right that the anxiety comes from not knowing what to do. It’s going to be different for each person, but if it’s an emotional response, maybe it should be dealt with in an emotional way. Any time you’re having anxiety, there’s an underlying fear; can we get at that fear? Can we talk about some of that and learn how to be there for one another in the discussion rather than avoiding it and feeling like it’s too big or too much?

JA: There’s a thread of gender in the book. There’s this group of nameless men who keep coming back, and the brother has to go to war and that violence forever shapes him. There is also a strong theme of friendship between women. The ways that these expectations imposed on us in relation to gender shape who we are, what we are exposed to, and how we hold those traumas and carry them with us.

AH: I was absolutely thinking about the harms of patriarchy throughout this and what that looks like for men, women, and nonbinary people. I did want to look at how the harms of patriarchy show up in this particular world and I think it’s something that we see a little bit with the brother character and the harms of war. There are also moments where the past traumas with the narrator and these faceless men who are described only as “the men.” It’s meant to show the lack of individuality in moments of violence. They become this larger system, machine, something, that is taking away from identity in many ways. That violence becomes its own character.

JA: You obviously thought so much about language in this book. Some elements you just describe, others you leave vague, some you name. There’s always a tension, right, in how we name something? Naming something can be an act of colonization in the way they can be imposed, but a name is also a form of knowing, of intimacy.

AH:I know this comes up with a lot of writers around naming. In a number of Ursula LeGuin’s books, there are characters who have multiple names but there is one true name, and that is given by another character. I intentionally waited for the characters to name themselves in the drafting process and I realized I wanted there to be as much time to go by for the reader as time had gone by for me as the writer. The names encompassed other elements and were in harmony or concert with their environment. To me, that felt right. It felt like it represented collectivity.

The tension you’re talking about is an interesting one. I certainly don’t think I get around it in this book, even after the characters name each other. When they name each other, there is this familiarity and they see each other differently, but there’s that pinning down that happens with identity when there’s a name. I don’t know if it gets around that tension at all; it’s still quite there.

JA: Part of the book is about deep griefs, but there is this longing from the characters who want to get out of the darkness. What do you think the role of grief is in developing joy?

AH: I think that they are one in the same, in many ways. It’s a strange thing to say, but in my grieving process, it has always felt like an act of love to me, and an act of joy. And when I have felt joy in life, it’s because I have recognized my mortality or the mortality of others. It feels very much entwined.

In Sift, there are moments from the past where the narrator is talking about joy. There’s a moment in the field with music and there’s a moment at the grocery store, getting bread: small, small moments that didn’t feel like much, but now having lived through so much chaos and trauma, they hold a lot of medicine and joy. They are things that the narrator keeps calling on as a type of coping mechanism. I don’t know if I could write a grief narrative without including joy. Grieving is recognizing some of the joys of life.

JA: Do you feel like that’s part of your compulsion to write, especially in this current landscape we’re living in? You’re making something beautiful in a dark time.

AH: Yes. This is also the difficulty. I don’t want to aestheticize the environment or the horrors of the environment in a way that might ameliorate that horror. It’s a very tricky balance. My attempt is to be in the space of grief or of trauma or of a deep sense of loss or remembrance and witness of the degradation of the environment. I feel like as an artist, trying to create it in a way where people can still see it and hold it, but not be so beautiful that it distracts from the realities. It’s something that’s very hard to do and I don’t know if I’m successful at it, but to me it felt like the lyric of it, the music of the prose, was the beauty and that allowed me to do whatever else I feel like I needed to share with the content of the piece. My hope was that it would be a balance.

JA: It’s hard because you don’t want to go the other way, either. For me, if I read straight environmental horror it makes me feel like I can’t do anything.

AH: When I was working with the editors on writing the synopsis for this story, I kept bringing in the darkness and they were saying no, no, there’s lightness and joy. I was bringing in more of the grief aspect and they helped remind me, as you are reminding me, that there is a lot of joy mixed up with the grief.