Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

Tracy O’Neill’s new novel, Quotients, is the global story of Alexandra Chen and Jeremy Jordan: their growing love, their sealed pasts, their connections to vast intelligence agencies, their hopes to feel whole while still withholding. They marry, move, change careers, adopt. They try not to lie, so they mislead. Of the novel’s background, of the shifting, insidious space behind, and often between, Jeremy and Alexandra—well, this is the world. History. Reality. The world of the 7/7 London Bombings, of call centers and hedge funds and catfishing and social media obsessions, of The Troubles, Operation Banner, the Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment. The tension within this landscape produces an accomplished work of art with encyclopedic reach and poetic concision.

On the page, O’Neill is a constructer of both bright high-rises and pulse-deep perceptions. She makes connections between continents of information. She unpacks the words that form a name. A lemon is “a great yellow orb.” Family advice is “legacy wisdom.” The application process for an adoption: “To become a family, their hands filled blanks.” A couple lies to avoid “becoming quotients.” On the phone, I found O’Neill—a National Book Foundation 5 Under 35 honoree—to be just as insightful as her narrator. We talked about some of the book’s themes, such as the value of privacy, the construction of the self, the misleading comfort in numbers.

The book’s cover—a lined landscape of slightly tilted geometry—has the same dramatic ambiguity as its title: “quotients,” a word from the language of mathematics, a referential language, a system of clamped meanings—yet, as word alone, “quotients” takes on a dislocated longing, a lyrical grief.

Alexander Sammartino: There’s a scene late in Quotients when two characters are talking about posting on the novel’s social media platform, the cleverly named Cathexis. One character asks: “What’s the worst that could happen if strangers knew the happiest part of your life?” And his friend responds: “Anything you say can and will be held against you.”

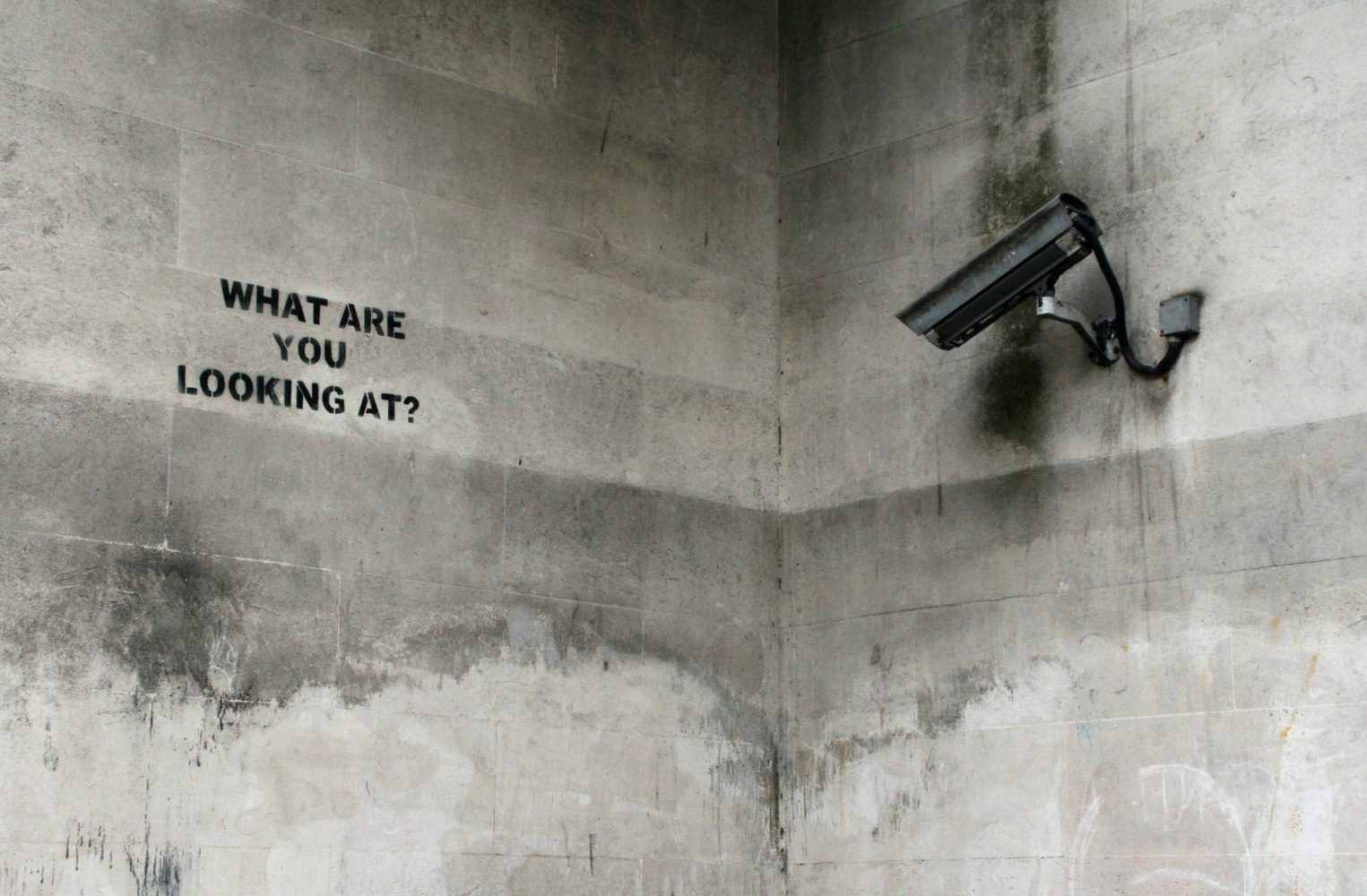

I thought we could start the interview here, with a discussion on the value of privacy, since this feels like a central tension in the book—that is, the characters in Quotients often seem to be either struggling to obtain privacy, or, having obtained it, are struggling with the consequences of privacy. Privacy also feels like the ultimate existential struggle in the information age: what meaning, if any, can be found in the unseen life.

So I want to begin by asking, do you believe there is something sacred in privacy? And, if so, what specifically do you think is important about privacy to the characters in Quotients?

Tracy O’Neill: We have the obvious problem of surveillance capitalism. But I think privacy is also important to being able to experiment with thought and affect, to play with and consider ideas that perhaps are not going to be your permanent position on a particular subject, and grow from discussing and processing them, as in—-just for one example—therapy. So this is not just about public life but also in our personal lives. The characters in Quotients—many are trying to find a stronger sense of self or stronger relationships. And I think that feeling safe to take risks in both regards matters.

In the Information Age, information that we give is used often not in the way that we intend, whether that is to sell us things, on mortgage decisions, or to track and discipline political speech. Think about how facial recognition technology—built with images from platforms like Flickr where users wanted to simply share moments of their personal lives—has been used to identify protesters. We are in a terrible position right now where online spaces that we use for communication and expression are weaponized against free speech.

When we look at this current moment—people, say, having Zoom events, or kids using video conferencing for school—we don’t yet know what some of that data will be used for. Then the question becomes: how do we feel safe to cultivate our identities, express ourselves freely, or risk connection in online spheres where information may be used for something other than what we wish it to be? Some of the characters in this book want to push back against violence in their lives, but they don’t know if they can safely.

AS: I love this distinction between surveillance capitalism and a notion of self, and I think both are explored in Quotients: you’re able to show these external consequences related to privacy, but also for the characters what’s at stake personally, emotionally, spiritually. And I think there’s this interesting tension there, because in our most private moments—that’s when we’re able to commit acts of great dishonesty. That’s true of the relationship at the heart of the novel, with Jeremy and Alexandra. I’m wondering if you can say a little more about that—about how, in our private moments, when we are capable of defining ourselves, we are able to most betray those we love.

TO: That tension is so central to the book. Early on, a lot of the cautiousness in Alexandra’s character has to do with her sense of always being perceived: there’s a way in which she’s anticipating a gaze on her. And that makes her even more secretive. There are a couple of moments in the narrative where she’s sort of testing the boundary to see how Jeremy would perceive something that she is considering saying or considering talking about, and he tends to fail these little tests because he is also performing this role in which he is not somebody who has a rather large secret about his own past in intelligence work.

In this book, it’s not that I wanted to suggest that privacy is unimpeachably the most important value, but, rather, that privacy is valuable specifically because it may afford openness in certain ways that the characters tend not to take. I don’t know if that answers your question.

AS: It totally does.

I also thought it was brilliant to have the narrative time be Jeremy and Alexandra’s relationship, how they’re our point of access to these bigger organizations. Can you talk a bit about that decision?

We are in a terrible position right now where online spaces that we use for communication and expression are weaponized against free speech.

TO: I have asked myself a lot of questions about what the novel is supposed to do as a form, generally. What makes the novel matter. What effects are supposed to occur in the reader. And although I suspect that we have undervalued certain things that the novel can do—like presenting a political rhetoric, or ideas—I acknowledge that most people are probably reading with the sense that fiction’s primary recommendation is its ability to confer emotion, or the feeling of feeling.

I wanted to use this relationship in order to accomplish that function and simultaneously be working in these other modes which are often associated with other forms of discourse or text, like journalism or scholarship. I was thinking about their difficulties in forming a loving, safe family as synecdochic for our difficulties in forming a society of love and safety.

AS: Your novel reminded me about something that is so inherently special to the form, something the novel can do far better than film, which is the ability to show the consequences of time passing. I think this is partly a result of you choosing to foreground Jeremy and Alexandra’s relationship, how we see this couple age together, the consequences that come with age.

What’s also interesting about this relationship is that both people, within their respective communities, are outsiders: Alexandra is an Asian American woman in London; Jeremy is, well, because of his secrets, his history in intelligence work, he also remains an outsider. I was wondering what connections you saw in their histories? That is, what made you conceive of this relationship, between these two people, with these sets of properties?

TO: Both of these characters are very aware of surfaces. The way in which people perceive them is both different from who they are and a part of how they negotiate their identities. So I think one of the ways in which they’re similar—and maybe they don’t even entirely sense this about each other—is that they’re always trying to represent themselves to others in a way that will ferry them toward love, security, happiness. At the same time, their relationship fails at moments they’re secretive with each other. If they were to sort of pull back the scrim, they might find each other to be more empathetic than they anticipate.

AS: To shift a bit here, I want to ask about the 7/7 London bombings, which, in the timeline in the novel, happen early on. What drew you to that specific event for Quotients?

TO: I was interested in writing about a terrorist event that was not on American soil, because it was important to me that this was a book that had a global plot. I wanted to get at the way in which the moment that we live in is not only an information age but also an age of globalization.

The 7/7 Attacks were not centered around a single location, like in the way that we conceive of 9/11 being centered around the Twin Towers. They were suited to portraying that sense of being surrounded by terror, the sense the characters have that when a terrible thing happens, it doesn’t mean another terrible thing isn’t going to happen.

AS: So I also want to ask about The Troubles. At one point Wright, a former spy, says: “Everywhere is Belfast with a different flag.” What brought you to The Troubles?

TO: I wanted to step away from conceiving of terrorism as grounded in jihadi extremism, which I think we’ve too often tended to do, at least in the United States. It was important to me that in The Troubles there is some moral ambiguity tied to the use of terrorism for the purpose of Northern Irish independence. In this book, I was really trying to critique some of the ways in which our attraction to and reliance on data, categorization, and quantification often elides a more complicated picture. So I was interested in the Troubles because there is not a completely neat overlap between the Protestant-Catholic divide and the divide over self-determination. You also have people fighting each other who look like each other, and that you can’t see the ideological difference—was almost an oblique tie to how the identities of people online are made anonymous.

There’s also that the Good Friday Agreement was only a couple of years after the internet became commercially available. It could be said to coincide with the transition into the Information Age.

AS: I want to talk about two sentences that I love.

Here’s one, which comes from a scene when Jeremy, at a bar in New York, is watching the bartender cut a lemon: “Jeremy watched the man scalp an arc of skin off a great yellow orb.”

Also, from the prologue, when Jeremy is working in a call center: “Sound huddles waves into intimacy.”

Can you talk about these sentences, as well as about your relationship to language as a writer?

TO: I’m often thinking about sentences in a few ways.

The first example you gave—“Jeremy watched a man scalp an arc of skin off a great yellow orb.”—is an example of a circumlocutionary technique. It is trying to get at the feeling of feeling, the textures of experience. In that sentence, yes, there is the physical description of what’s happening, but it’s also that we are seeing this moment through Jeremy’s consciousness. This is a man who has the stuff of war so deeply entrenched in his psyche that it becomes his reference point. Scalping. There’s a violence to it.

When information is extracted and then militarized or used for surveillance capitalism, we aren’t made safer.

That other sentence—“Sound huddles waves into intimacy.”—I want to build out this psychological and thematic substrate. It’s a scientific fact I gloss, but I’m trying to project a larger thematic note about what happens in the book and also get at the way Jeremy is thinking about intimacy. In this prologue, he’s involved in some magical thinking. He’s bargaining. He’s thinking if he’s a good enough guy, then nothing bad is going to happen to Alexandra. I hope the magical thinking is made slightly more emphatic by using that language of science as a counterpoint.

Syntactically I am often trying to create a shift, a plot of sorts, so that a reader’s understanding of what is happening in the course of a sentence changes. I don’t want someone to read the first half of a sentence and anticipate the second half all the time. I’m using sound to drive the work forward rhythmically and also create certain groupings, senses of pattern and anomaly. That is particularly important in this work, which is about people trying to see patterns but finding their stories don’t fit into the schemas.

AS: I know we began the interview with this broader discussion of privacy, so to end I thought we might talk about our larger cultural obsession with knowledge and how that appears in Quotients.

Of course in some sense numbers are symptoms of our yearning for omniscience, and I was thinking of how we see this in your characters. For example, Alexandra has an app that lets her track her mother’s purchases and general online activity. You write: “Now she could see where the money went, she could see what her mother wrote, and it mollified something to know she could know.”

So, lastly, I want to ask: what do you think is mollified in our ability to know? Both for these characters, and, maybe, more broadly, at this particular cultural moment?

TO: All of these characters are facing a world that feels very dangerous. Part of that danger is not knowing what is true or who to trust. They don’t know if they can trust online friends, their governments, their loved ones.

Early in the book, Lyle and his friend Bri are bantering. They invoke Hannah Arendt: “If everybody always lies to you, the consequence is not that everyone believes the lies, it’s that no one believes anything any longer, and with such people you can then do what you please.” The characters in Quotients are facing the potential to be immobilized by misinformation and disinformation. How can you call out state violence when you don’t know what’s true? How can you know who to affiliate with, who your community or your family or friends are, online? How does that affect how you love? How can you speak freely if your signal boosting becomes data collected by police to then target protest? And how does that affect how you politically organize?

One of the things the characters want mollified for them is a sense that their worlds can be trusted and that therefore they can exert agency in their lives. It comes down to this fundamental question about whether they can enjoy a level of self-determination, create bonds, invest in a better future. They want to lead lives that feel existentially worthwhile, but they confuse information and knowledge.

Throughout this book I wanted to trouble that distinction. I wanted to convey that when information is extracted and then militarized or used for surveillance capitalism, we aren’t made safer. We have to gamble love in our relationships, love in our communities and global politics without falling back on the myth that weaponized information will save us.