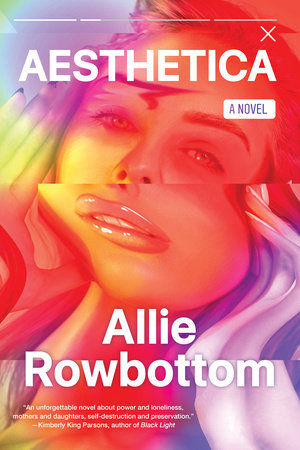

In Allie Rowbottom’s novel, Anna is preparing to have an innovative, high-risk surgery known as Aesthetica™ that will reverse all her previous plastic surgery procedures, supposedly returning her to a truer version of herself.

At 35, Anna’s influencer career is long-ended, and she now works behind the counter of a department store selling beauty products to other women looking for self-love in the skincare aisle. Though it’s been said that “the only meaningful change comes from within,” like most of us, Anna isn’t immune to the allure of happiness promised by neatly packaged products whose price seems easier to pay than serious self-reflection. She knows from experience just how anesthetizing beauty products and procedures can be to the pain of human experience, but in the hours leading up to Anna’s last surgery she is forced to confront the traumatic events of her past that resulted in the end of her social media fame.

Told in a split narrative alternating between the chaotic moments preceding Anna’s surgery and her tumultuous coming-of-age as an Instagram model, Aesthetica examines the lengths we go to in order to love ourselves. Anexploration of womanhood and aging under the influence of social media and late-stage capitalism, the novel examines how internet culture impacts bodily agency and gender. At its core, Aesthetica is about the desire to be seen as we want to see ourselves.

I spoke with Allie Rowbottom via email about social media’s impact on self-perception and the difficulty of connecting with others online and in real life.

Shelby Hinte: I’ve been waiting for a book to come out that addresses the relationship between social media and body modification in an original way, and I definitely think your book does. Can you share a little bit about what inspired you to write this novel?

Allie Rowbottom: I felt inspired to write Aesthetica for several reasons, not the least of which was desperation, shame, and a personal obsession with several Instagram models, their ever-changing bodies and insistence that puberty, not plastic surgery or Photoshop, was the reason for those changes. But mainly I wrote it because I was in the same boat as you in that I wanted to read about image culture, beauty standards, and the lengths many women (including myself) will go to attain and uphold those standards —and nobody was writing about it! Especially not without finger wagging. I suppose I generally just write what I’d like to read and hope others feel the same way.

SH: I like that phrase “finger wagging.” It feels like a lot of women, even women who promote lifting other women up, can be guilty of this (myself included)—especially towards women who go the distance to uphold so-called patriarchal female beauty standards. It is totally hypocritical to say that on one hand women should have full autonomy over their bodies while on the other hand discrediting certain choices, such as choosing to get plastic surgery, as antifeminist. Personally, I would consider myself a feminist, yet I often feel torn on how to make sense of both wanting to say “damn the man, you can’t tell me how to look,” and also wanting to feel attractive and desirable. Sometimes it feels impossible to strike a balance. Have you had any major insights on how to navigate this precarious territory?

Women fighting with each other is produced for the masses as entertainment [because] keeping us split is what upholds the normative power structure.

AR: Finger wagging is just another symptom of a culture that has a vested interest in splitting and disempowering women. We (all) do it because we’ve literally been trained from birth to do it. When women judge other women for augmenting their bodies in ways that appear to pander to the male gaze, or when women judge other women for not augmenting their bodies, they are making assumptions and reductions that actually serve to support a culture in which men dominate. That’s why women fighting with each other is produced for the masses as entertainment—keeping us split is what upholds the normative power structure (exhibit A: many reality TV shows, though I want to point out that some shows that start out this way turn into abiding portraits of women’s power against all odds, as is the case with The Real Housewives, in my opinion). But bottom line: we’re all human. When we see someone inhabiting a physicality that threatens us for one reason or another, we’re going to judge them for it. I’m as guilty of this as the next person. But I think what writing this book has helped with is softening that impulse, especially when it comes to judging myself. For a long time, most of the finger wagging I did was directed at myself.

SH: I’ve heard a lot of warnings against writing about the internet, and while some of those warnings feel dated or unreasonable at this point, I do find that depictions of the internet in literature sometimes come off as cringey or unrealistic. That wasn’t true with Aesthetica though. The way you write about the internet, and social media in particular, feels accurate. What sort of challenges did you run into while writing about social media?

AR: I think the key for me was not to try to write about the internet per se, but rather to focus on my characters, their core wants and woundings, and then incorporate the internet to the extent that it had any bearing on their lives. For that reason, I don’t think of Aesthetica as a book about the internet or social media. I think of it as a novel about a deep, human yearning to be seen, and how that yearning amplifies and augments under the pressures of contemporary patriarchy.

But I know what you mean. Why are writers hesitant to write the internet? Why is literary fiction about life online often so cringe? I think a lot of people who are publishing books now grew up at a time when the internet wasn’t so pervasive and are therefore hesitant (or unable) to chronicle it with authority. That will change as Gen Z grows up and starts publishing. The internet is also always changing, so there’s a question of relevance. Will my novel about an Instagram model still feel urgent and important in ten years’ time? I think so if only because the underlying principles of Instagram (scopophilia) are the same underlying principles of Seventeen Magazine twenty years ago, and they’ll remain the same underlying principles of whatever image-based platform comes after Instagram.

SH: One of the things I loved most about Aesthetica is it reveals the deep layers of manipulation that go into the images we see rendered on the social media accounts for public figures — both in terms of manipulating the bodies those images depict, and in the altering of the actual images themselves. It felt a little like getting to see the behind the scenes work of curating an influencer’s public life. What drew you to writing about this world?

In addition to leaning on old food and exercise rituals for comfort, I was getting really into Instagram, consuming images of super hot, thin, young women, and comparing myself to them.

AR: The experience of body dysmorphia has been a prevalent one in my life, as it is for many women. By the age of twelve I had an eating disorder. By the age of fourteen, that eating disorder was a serious one. I went to treatment for it when I was in college, which helped, but it stuck with me and when my mother died in my late twenties, I turned toward my old restrictive habits in a big way. I was aware I was doing it, but I was also in crisis. And to make matters worse, in addition to leaning on old food and exercise rituals for comfort, I was getting really into Instagram, consuming images of super hot, thin, young women, and comparing myself to them. Even before I fully understood the Photoshop and surgery going on behind the scenes, I could feel what the images were doing to my brain, so worrying what they would do to the brain of someone half my age was the logical next step. The next step was wondering what creating and disseminating those images would be like for the model herself, because I do believe that in addition to some truly evil content creators out there (The Kardashians), there are many young girls who despite their veneer of perfection are irreparably damaged by the images they post. Once you start to bend reality, either with FaceTune or surgery or restriction or whatever else, once you then receive praise for that bending, it’s hard to return. It’s hard to see yourself with any clarity. That’s a great tragedy of many women’s lives: that no matter how well they conform to beauty standards, they can’t see themselves clearly and can therefore never claim the power their beauty might entail. Another ruse of patriarchy, I’m afraid. And all the more reason to work toward alternative valuations of beauty.

SH: How do you work through the feeling of conflating the self with your work/success? Those feelings of pressure or discomfort?

AR: Conflating myself with the subject of my work is part of what makes the work any good. Conflating myself with my career is where the trouble starts. Even worse is conflating myself with the negative things people say about my work and career. But there will always be people saying negative things if the work/writer is any good. That’s just a fact of human behavior, the internet and challenging art disseminated on a certain scale. It also appears to me to be a fact of human behavior that we zero-in on the negative stuff and assign it more weight than the positive. Like, for some reason, the word of some random book blogger who dislikes my novel counts as much if not more as the support of a writer or critic I deeply admire. Someone told me recently that this response to negative feedback has to do with fight or flight, which makes sense, but I’m still doing my best to override it. My advice is this: as painful as it is to see a one star drag down on your goodreads page, you actually don’t want everyone to like your work. If you’ve made work everyone likes, it’s middle of the road and unchallenging.

SH: What were some of the difficulties you faced while publishing Jell-O Girls? Have you had any of those same experiences while publishing Aesthetica?

AR: Blissfully, not writing about real people has taken from me some of the difficulties I had publishing Jell-O Girls. Related to what I was just saying about goodreads and the internet’s democratization of book ratings and reviews, I found writing and publishing a personal narrative about my mother’s death and then having randos on the internet rate it on a scale of one to five, often including digs directed at her, deeply troubling. I also found the critical acclaim troubling and I still don’t know why. I think it just felt so exposing at a time in my life where my grief was really raw and unprocessed and my sense of self was somewhat obliterated. But I did learn a lot about the publishing industry. Later, observing and supporting my husband Jon as he went through the process of publishing his novel Body High also taught me a lot. So going into putting Aesthetica out into the world I think I have a good grasp on how to build off the books that came before. Number one takeaway is this: no matter who your publisher is, no one cares about your book as much as you do. It’s up to you to promote and push for your work. I realize a lot of writers are like that’s not my job, and maybe it shouldn’t be. But it is what it is.

SH: Earlier you mentioned that Aesthetica is about yearning to be seen, and I think that really comes across, especially in the scenes between Anna and her mother. To me, that yearning to be seen feels like a yearning to connect, and I think some of the work Aesthetica does is illuminating how difficult meaningful connection can be in our digital age (though maybe it’s always been this hard—I am a millennial so I only know this way). Why do you think it is so hard for us to connect with others these days?

AR: I mean, we are all addicted to our phones. That’s an automatic, fairly recent barrier to connection, though of course our phones and social media apps do connect us, also. But I think the constant rush of information is such an overwhelm to the system that it can be hard to sit down and think for ourselves or talk to others. Maybe I sound old saying this, but it’s also just a fact: people who have grown up on the internet are having trouble socializing irl and it’s causing real problems. Then there’s the Twitter mob thing, the number one reason I am on Twitter is solely to repost stuff and leave. I find it so depressing. People rush to weigh in on whatever topic du jour simply because other people are doing it; everyone seems so ready to cancel based on nothing but what some other person said. Why is that? I suppose it’s loneliness and a longing to belong, to prove oneself “good enough” to be accepted by like-minded others. All very wrenchingly understandable. But the outcome is often terrible. All to say I guess maybe we’re having trouble connecting because the tools we’ve adopted to do so are failing us.