If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I met Jess Zimmerman in 2017 at Madame X, a velvet-swathed Manhattan lounge, where she and Liz Gorinsky were releasing the party game Goth Court. Afterward, I followed the courtiers to a post-punk danse macabre, where Zimmerman and I talked about goth business and this website (where she has been the editor-in-chief since 2017).

Now, we are here to talk about monsters.

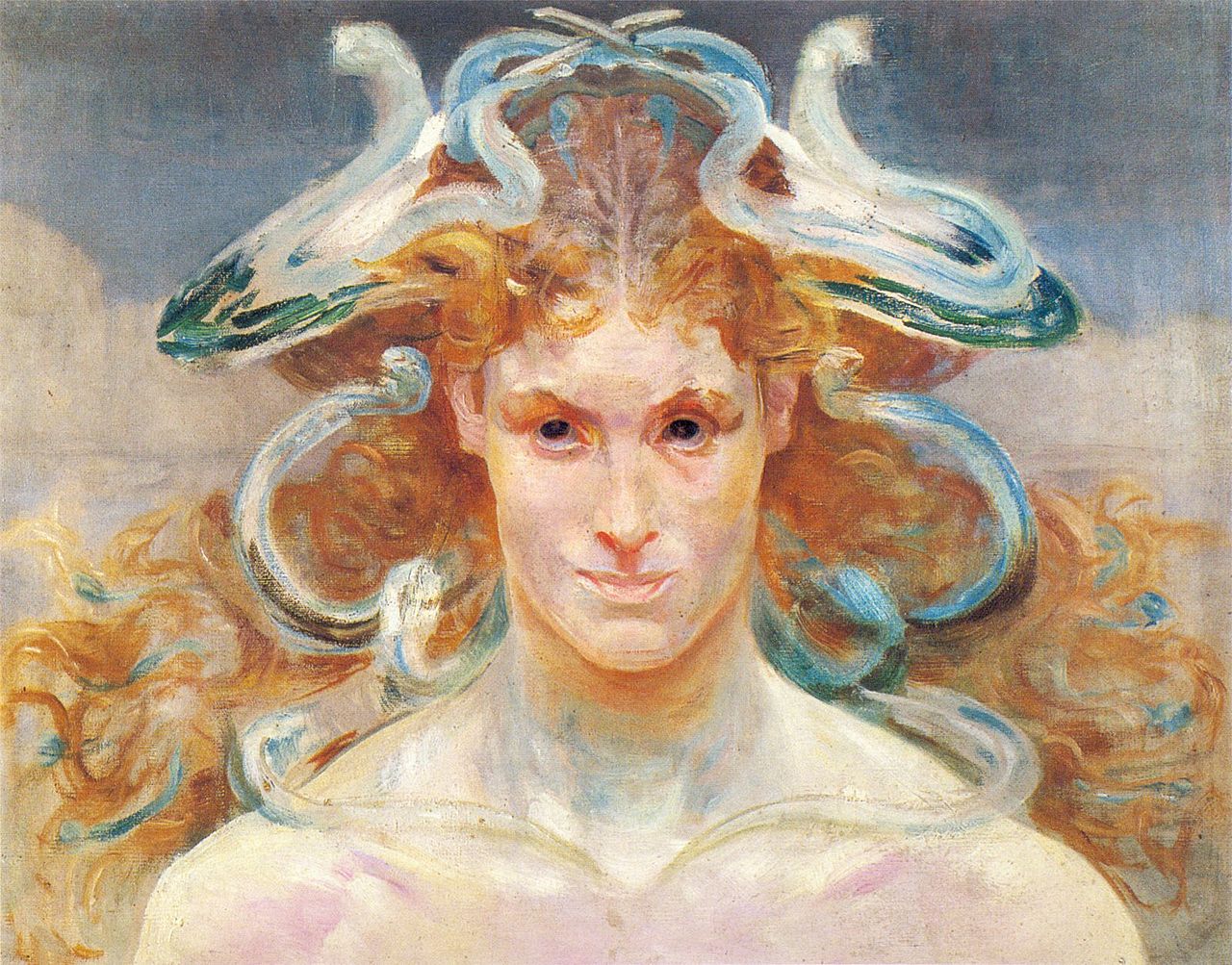

Zimmerman’s essay collection, Women and Other Monsters, takes female monsters from Greek mythology and explores their grotesqueries as patriarchal metaphors. Feminine anger, sexuality, ambition, and other hungers manifest as dog-crotches, whirlpools, talons, and bird-bits.

Medusa offers “Ugliness for an infinity of options, a universe unconstrained by any desire except your own…Beauty may be a key, but a key is not the only way to open a door; you can do it with a battering ram.” Today’s Furies are “Social Justice Warriors,” the “supposed taunt” that “accidentally sounds cool as hell.” Charybdis—the deadly whirlpool who began life as “a voracious woman who was cast into the sea by Zeus as a punishment”—personifies hunger, “a cautionary tale, not only to sailors, but to women: hunger destroys those around you.” Echidna, the Mother of Monsters, speaks to creation: “even the woman so tightly yoked to her shame that she no longer knows which one of them is the parasite, can bring something ferocious and valiant into the world. It may not feel good, but then again, birth never does.”

Over G-chat, Zimmerman and I discussed our shared childhood obsession with D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, whether or not harpies are bulletproof, how to get in Scylla and Charybdis’ group chat, and the universality of living inside a rotting meat-coated vehicle.

Deirdre Coyle: First of all, shoutout to D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths.

Jess Zimmerman: THE GOAT. Literally the goat, since all the gods were fed by a goat as babies. No gods without goats.

DC: Personally, it really blew my mind when I hit middle school and realized that the women D’Aulaires’ referred to as Zeus’s “many wives” were actually his mistresses, and not always consensually so. Did you have any moments of shock when you moved from D’Aulaires’ to Ovid and Homer?

JZ: Oh, that’s a great question! I must have, because I was a D’Aulaires’ obsessive from literally preschool, so not only was I getting this slightly predigested version of the myths (I say that with love!) but I was also processing them through an exceptionally oblivious mind. For sure there’s more sex in mythology than I initially understood! The whole Ares/Aphrodite/Hephaestus love triangle is kind of played down in D’Aulaires’ and, in my recollection, played very up in Edith Hamilton for instance.

DC: Yes! There is a lot of euphemism in the way those stories are filtered for children.

JZ: And not only sex but sexual assault, which is often still euphemized even in the adult texts. We had a great essay about the translation of “rape” in the Metamorphoses; people find ways to say anything else. You get Daphne and Syrinx in D’Aulaires’, but I definitely remember reading the Metamorphoses in college and getting to Myrrha and being like “HANG ON.”

There’s a degree to which the engine of Greek mythology is women’s pain and exploitation. And that absolutely doesn’t come through when you’re reading these stories as a kid, or even in school (I did a Greek mythology unit in 6th grade, and the Odyssey in high school, and Ovid in college). But that’s a pretty apt metaphor for the patriarchy, right? All the stories you’re being asked to analyze and in many ways internalize are built on women’s pain but nobody mentions it. Not only sexual assault but also the forcible mutation of feminized bodies, basically all of Ovid is women turning into other stuff often through no choice of their own. And sexual punishment, like Pasiphae and the bull.

DC: Right, and by actually focusing on these monsters’ origin stories—as these essays do—we can see how those patriarchal metaphors are still in play in the way people still use monster terminology.

JZ: This is a good spot to say that I’ll sometimes say “feminized” because when I talk about women I’m talking about people who are treated as and interacted with as women, some of whom aren’t women at all—when society puts you in the space it’s designated for “women” it often doesn’t ask about your identity first! So in mythology Hyacinth also ends up in a similar role, even though he’s a man.

DC: I also wanted to talk about your decision to focus on Greek mythology particularly. You write that you focus on monsters from Greek antiquity “not because they’re the most interesting stories, but because they’re complicit,” that they’re “tight little packages of expectation seeded into the culture.” What are some of your favorite monstrous women from other folkloric traditions?

All the stories you’re being asked to analyze and in many ways internalize are built on women’s pain but nobody mentions it.

JZ: Oh absolutely the penanggalan, which is a Malaysian monster which takes the form of a woman’s head detached from the body but with the intestines still attached. I believe she has a body also but can detach her head at will. There are some great monsters in other traditions that simply aren’t mine to talk about—Jami Nakamura Lin has been writing about some of them for Catapult. And I would be so delighted if someone did this exact same book for other cultures! I just can’t really put myself in a position to be like “this monster from a tradition that has nothing to do with mine? It’s SEXIST.” Whereas the stories of Greek antiquity are really baked into Western culture, like there’s a reason Classics and “the classics” use the same term.

DC: Hence the frequent use of the term “harpy” in recent U.S. politics.

JZ: Yeah, so many of these stories have seeped into our everyday speech! Harpy, Gorgon, “between Scylla and Charybdis.” People talk about ingenues as “screen sirens.” I think it’s significant that when I first read Ovid in college, it wasn’t for anything in the Classics department—it was for an early modern literature class.

DC: Right, because understanding the Western literary canon (however one may feel about “the canon”) requires a certain knowledge of classical mythology.

Western literature is very autophagous, people are always looking back at something in the past to tell them what’s valuable in the present.

JZ: Yeah, you basically need mythology and the Bible. The people who were creating the literature and art that we think of as sort of the wellspring of (Western, European, and therefore privileged in the literary canon) culture were looking back to these stories as their guides.

DC: Which seems strange in 2021, but it still applies to so much of pop culture.

JZ: The Rosetta stones of Renaissance literature and art! And therefore of any literature and art that looks back to Renaissance literature and art as the baseline of quality. Western literature is very autophagous, people are always looking back at something in the past to tell them what’s valuable in the present.

DC: So these essays are hybrids themselves—CHIMERAS IF YOU WILL—of folklore, memoir, and history. Can you talk about the experience of grafting your own life—as well as historical and current events—onto these ancient powers?

JZ: I think for me writing is fundamentally always a process of metaphor. And so in a sense, I didn’t even think of it as “here I am kind of suckering my life story onto the side of this big myth like a male lanternfish,” which when you think of it is an act of great hubris! Which lord knows the Greeks did not countenance. It’s more like, okay, in many ways a myth is already an extended metaphor, stories exist and persist in order to stand alongside the world and give you a framework for understanding it. So what happens if we sort of dissolve and rebuild that metaphor? What happens if we take it apart, show how it was put together, and then use it to form another shape? Like Legos, but figurative language.

A myth is already an extended metaphor, a framework for understanding the world. So what happens if we dissolve and rebuild that metaphor?

Essentially I didn’t think of it like “I am putting my life story into conversation with this myth.” I thought of it as, okay, this myth is already supposed to be in conversation with my life. Stories like this carry a message, which is not always one we are led to recognize, but it influences us all the same. So rather than creating that relationship, I’m reformatting it. And of course, the “I” here is just a stand-in for anyone! There’s plenty of personal anecdotes, but I don’t think of it as a memoir, because to me if this were really about me it wouldn’t be interesting, who cares. What’s interesting is that it’s about us. And I’m simply the one of us I know most about.

DC: And I think any woman (in the broadest sense, again) will relate—I certainly do—to concepts like “Nobody really likes to think about how we all ride around in vehicles of meat that are rotting underneath us for most of our lives, but for a straight man looking at a woman—or anyway, for the Male Gaze looking at a woman—that fact feels like not just a downer but a betrayal.” Sorry, that’s a comment more than a question, and the comment is “YUP.”

JZ: Hahah yes! I mean the whole idea of “us” in writing is… vexed. Like, I obviously can’t write for everyone, because my experience is very limited by being white, American, middle-class, any number of things, so I can be conscious of trying to look beyond those limits but at best I’m putting peep holes in the walls. But there are a few things you can truly say “us” about and “all our bodies are rotting under us” is one of them!

DC: We are all made of meat. Did any particular monster—or concept—act as your point of inspiration for the collection as a whole?

JZ: That is a great question and requires me to think back to a time I can barely remember, which is “before 2020.” When this started to become the germ of an idea, I think I’d already written the essay “Hunger Makes Me” for Hazlitt, which became the substrate of the chapter on Charybdis. So I wasn’t necessarily thinking in terms of mythological monsters but I was thinking in terms of desires and traits and needs that are seen as somehow grotesque in women.

So I think if I can pin it all on anyone it’s probably Charybdis, whose origin story literally is “she was so hungry she became a whirlpool.” And then of course if you’re thinking of Charybdis, you necessarily think of Scylla, and then it’s all over for you bitches. (Even though actually I wrote the Scylla essay way later! It took me a while to figure out what her story means, even though in retrospect it’s both obvious and kind of goes hand in hand with the idea of hunger and bodily needs.)

DC: How does one become part of Scylla and Charybdis’s group chat, is the real question.

JZ: I feel like the way in is almost certainly Circe, she’s the one who started the chat and keeps renaming it.

DC: Yes, I’ve always been obsessed with Circe—and thinking about her relationship with Scylla is…fraught, to say the least.

JZ: And actually reading Madeline Miller’s Circe may well have been part of the thought process here, like thinking about the stories underneath these stories, the lessons we’re supposed to be learning from them that we can refuse to learn. By the time it came out I’d been writing these monster essays for a year or so, but that book certainly convinced me that this was something we were ready for.

DC: If you could pick two traits from any of these monsters, what would they be and how would you use them?

JZ: Ooh! We’re talking like real monster traits here, right, not the excesses they’re supposed to warn us against? Like wings and snake hair, and not “anger”?

DC: Yes, real monster traits. No parameters.

JZ: Well one thing I didn’t talk about much in the book, but which is relevant here, is that Harpies are essentially bulletproof. And I think right now, of all times, it would be really nice to feel indestructible! Aeneas’s men try to hit the Harpies with swords and it simply does nothing. I know I said “bulletproof” but I guess that has never been tested. Let’s just assume there’s a certain nigh-invulnerability there though.

DC: Yes, “sword-proof” seems like it would lead to “bulletproof,” given a few centuries of Harpy evolution. I was terrified of harpies as a child because of The Last Unicorn, but now they seem pretty hot to me?

JZ: Oh man I rewatched that not too long ago and boy people’s idea of what children could handle was different in the ’80s. I was OBSESSED with The Last Unicorn but not only is it wildly dark, the Harpy absolutely has naked boobs if I recall correctly?

DC: SHE DOES, and she loves Doing Topless Murder. An icon.

JZ: Topless Murder is a trait shared by almost all of these monsters. Some of them can’t be said to really have breasts or human torsos but that shouldn’t stop anyone from doing topless murder.

DC: Agreed.

Sphinx power is that instead of a ‘mute’ button on Twitter, I have an ‘eat’ button.

JZ: I’m inclined to say I’d also like Lamia’s ability to pop her eyeballs out of her head, but honestly I don’t know what I’d use that for except as a party trick, and who’s going to parties right now? Oh, another niche one: blood from one side of Medusa’s body had healing properties! But that doesn’t go very well with being bladeproof. Imagine the keen irony of having healing blood but you can’t get at it. Okay so let’s say from the Harpies, nigh-invulnerability, and from the Sphinx, the ability to eat men if they don’t answer your questions properly.

DC: Powerful combo. That is kind of what happens on the internet, but usually it’s women getting eaten. The literal power seems preferable.

JZ: Sphinx power is that instead of a “mute” button on Twitter, I have an “eat” button.