If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

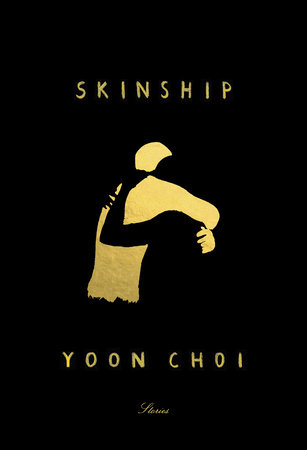

Yoon Choi’s debut short story collection has a striking cover: two figures, simply and starkly outlined in solid colors, embrace amidst darkness. One figure is the same color as the dark background, defined only through their hug with the other figure, who is glowing in yellow. One can almost feel the palpitating warmth and the tightness of the embrace. Reading the collection is a similar experience: I was struck by how Skinship kept returning to the idea of caretaking and intimacy, depicted in Choi’s strikingly simple, beautiful prose.

There are stories centered on decades-long marriages that are not quite falling apart; sisters who tussle with motherhood in opposite ways; unhappy households that are still compelled to stay together. Even while Choi explores the ways in which we fail one another, those cracks and fissures of human connection, her stories are remarkable for their warmth and compassion.

Choi’s eight short stories present an array of Korean American narrators, as they experience life and create families in the modern-day America. However, while it clearly centers on Korean Americans, Skinship also shows how there is no singular definition, how this identity is formed of many different experiences—from hospice helper Happy in “The Loved Ones,” who’s adopted from Korea, to classical pianist Albert in “Solo Works for Piano,” who seems utterly unaware of his racial identity, to young immigrant Ji won in “A Simplified Map of the World,” who makes an active effort to assimilate into typical “American” culture.

In my conversation with Choi, we discussed familial intimacy, what the word “skinship” means for her, and the role of time in writing.

Jae-Yeon Yoo: To begin with, what a perfect title! I thought it connected the ideas of kinship, intimacy, and—for those who come from a Korean-speaking background—Koreanized English in such a concise, provocative way. [“Skinship” in Korean slang doesn’t have an exact translation; it can be about physical intimacy, how “touchy-feely” someone is, and/or sexual compatibility.] Could you talk more about why you picked “skinship” as the title for your collection?

Skinship is such a huge part of Korean culture—where you see schoolgirls holding hands or the way a parent would touch a child. And that feeling of physical closeness, which is so absent now.

Yoon Choi: I first heard the word, “skinship,” from my mom, and I did think that she had just kind of come up with that on her own for a while. To me, the word has to do with a sense of physical affection, which is not necessarily sexual. I think that skinship is such a huge part of Korean culture—where you see schoolgirls holding hands or the way a parent would touch a child. And that kind of feeling that you can have through physical closeness, which was so absent during this time. For example, my sister lives alone, so she was quarantining and not being physically near another person. Longing for that sense of touch became more and more meaningful to me, as time went on and as I sat with this title. One thing I wanted to convey through the title is a sense of intimacy and affection, which is bicultural [with these Korean connotations], but it can also be just shared among all these different kinds of people, who are not necessarily lovers.

JY: Absolutely. I loved how your collection explored the idea of intimacy, which was often physical but not always sexual. I was struck by how you made me see the word “skinship” in a new way—I never realized kinship fit inside of skinship. Which felt fitting, as there was such an emphasis on family throughout your collection. Can you talk about motherhood, or more broadly, parenthood and caretaking, and what it means to you as a writer?

YC: You know, I was surprised (and I shouldn’t have been) that it was so clear to all readers that the collection was so family-centric. I guess I just wasn’t aware that those were the relationships that I was choosing to depict. I think that there are probably two things going on here. One is that I feel that immigrant children—I’m an immigrant, I came when I was three—have a very particular relationship to the immigrant generation of their parents. Of course, everybody’s experience is different, but I do think that most of us do come to a point in our life where we suddenly realize the sacrifices that were made on our behalf. And then your experience [growing up in America] has made complete communication with that generation impossible. There’s that distance, where all of the privilege that has been given to you—the education that you were able to have, the experiences that you have under your belt—have, in this ironic way, created a distance. There’s still that strong family connection and yet there’s also this tension, in which your parents’ values or language or culture isn’t quite creating an open dialogue. That is really interesting to me.

Your experience [growing up in America] has made complete communication with your parents’ generation impossible. All of the privilege that has been given to you has created a distance.

I think the other part of it is that I began writing when I was much younger. I went into an MFA right out of college. At that time, I found it really hard to write anything and I realize now it’s because I was so against writing about Koreans. I wanted to write something very not defined by who I was. I didn’t want to be pigeonholed. Which is not to say that I feel like all writers need to write about their ethnicity or their race; that’s just the particular case for me and would have been such a rich source for me to draw on [during my program]. I was very blocked, very stuck and when I left my program, I didn’t write for many years.

But, during the intervening years, I became a mom. I’ve got four kids, and it’s just great. One after another, they came; I wasn’t writing. But after my fourth kid was born, I went back to the computer. I think the thing that motherhood did for me—and I’m sure it did other things for me in a more profound way—but one thing is that it helped me manage time and expectations. I sat down and I was like, okay, I’m not going to try to be all these things. I’m just going to sit for an hour, then see what comes out. I think that freed me. I also definitely think there is time [for publishing]. And I feel like that you should wait for the time, you know? I wonder if I had started publishing right away, how that would have shaped my identity as a writer and a person. I’m glad you know I took the detour, had the kids. I went to law school for a month; I taught English foreign language as a foreign language in Korea for like one semester.

JY: Another through-line of this collection is its exploration of Korean American identity—and I appreciated how nuanced and varied this exploration was. Connected to this emphasis on plurality, I was so impressed by your ability to shapeshift, to slip into completely different “skins” or voices. We see this perspective switch happen even within one story, like “The Art of Losing.” How did you decide on this array of narrators?

YC: As the stories began to collect, I did begin to think of it as a collection and make very deliberate choices. For example, to do a first-person narrator for one story, if I felt that I already had too many third-person narrators. I also was deliberate in trying to choose an array of ages and sexes. If I had a grandfather [narrator], I might want to write something from the child’s perspective. So, I did very consciously have that in mind. And I don’t know if I was entirely successful in doing this, but I did, on the one hand, want to touch on certain iconic moments of Korean immigration; for example, having somebody own a 7/11-style convenience store. I wanted to touch on those things because I think that they can be stereotypical, but they’re also extremely true to a certain kind of immigrant experience, in which there were strong commonalities in the jobs that were available and in the choices that people made. But, on the other hand, I didn’t want to veer too much into stereotypes.

I did want to reflect a range because, you’re right, I do think that there’s a huge range, not only in the way that different immigrants experienced immigration and their sense of identity, but also at the age at which you are evaluating yourself. I think that that can also change; like I was telling you, as a younger writer, I just really was not interested and only grew interested much much later [in writing about Korean Americans]. As soon as I realized that the stories would become part of a collection, I did really hope that the book would have that sense of being as multiple as possible, while still centering Korean Americans and Korean immigrants.

JY: Are there authors who have been particularly influential for you?

YC: I mean, clearly I love Alice Munro, who opened up the idea of what a short story could be. Because, for a long time—although I now realize it’s not that uncommon—I felt like I was the only one who could sit in a writing program and not really know what a story was. Everybody else seemed to know exactly what they were doing. But for me, I was [asking] what is a story? Like, what is the experience that I want a story to be? Reading Alice Munro really unlocked this for me: the sense that time could contribute to the idea of plot.

Chang-rae Lee was just a huge voice. Not just his novels but his few personal essays. I always want to give him credit for the kind of emotional response that I have while reading his descriptions—say, how his mom specifically makes the kind of be, or the different ways in which you would call his name. I might be misremembering here, but I think I remember reading Alexander Chee about watching a Korean movie; something about the way the Korean father stood or walked, some gesture he made, was so emotionally authentic to [Chee]. What reading an essay by Chang-rae gave me was a feeling that an emotional response is a valid one—which is almost a stupid thing to say, I guess, because why wouldn’t it be? I guess I often was looking for an aesthetic experience when I read, but when I read [Chang-rae’s] writing, my response is very visceral, and I thought, “Oh, that’s okay. And that’s good.” So, I think that permission to strive for this type of response came from him.

JY: It’s funny to hear you finding this visceral emotional authenticity in Chang-rae’s work, because I felt that way reading Skinship. To be honest with you, I had a hard time initially thinking of questions for this interview, because my immediate reaction was just: “Oh, yes. Period.”

YC: Thank you. I can’t think of anything better to hear than what you just said. I’ve said this before, but I do feel like I write for a Korean reader. That was mainly what I wanted: to have more books like this—not just mine, but others’ as well—for the person who loves reading and is Korean.