If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

For me, reading Torrey Peters’ debut novel Detransition, Baby is akin to listening to your favorite hometown band headlining their first stadium concert. You end up marveling over how experiences you thought you knew well are rendered in utterly unexpected ways, and realize how patterns from your own life are deeply enmeshed in the concerns of a much larger world around you.

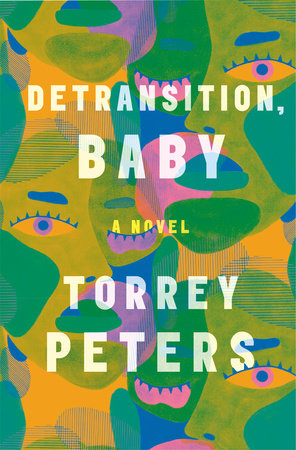

Yes, Detransition, Baby is centrally about the complex relationship between two trans women, Reese and Amy, as the latter detransitions and renames himself Ames, then gets his boss Katrina pregnant. The trio ends up trying to figure out whether it’s possible for them to form a family together, as they also navigate the limits and expanses of their genders. What may seem like a niche, insider-baseball trans narrative ends up being a novel that simultaneously nods toward and hilariously subverts the central concerns of classic cis, white, middle-class American fiction: the relationship between genders, the aftermath of pregnancy, the meaning and composition of family. As a result, Peters performs the kind of magic trick that’s the hallmark of great art, writing a novel that feels simultaneously familiar and utterly new at the same time.

Peters and I sat apart in our own spaces and typed in a Google Doc for an hour together, which felt like an erudite version of another familiar experience for many trans women of a certain era: typing anonymously in chat rooms as we try to figure out who we are. Though unlike back then, we now live in the world where it’s increasingly possible for narratives and ideas such as Peters’ not just to belong in the open, but to be admired and celebrated.

Meredith Talusan: So how are you dealing with the irony that as a person who had such a public position of trans authors not being served by mainstream publishing is now also the author who is arguably bringing trans women’s fiction into a particular kind of mainstream by working with a major publisher? How has your position with regards to these issues evolved in the time that you wrote and went through the editorial process for Detransition, Baby?

Torrey Peters: It is something of an irony! When I gave away my novellas for free (or pay what you want) online to trans women because I believed that “the publishing industry doesn’t serve trans women,” as I put it on my website, I was largely correct in holding that belief. But! A lot has happened in five years. A couple years ago, I looked around at the media landscape and Transparent was on TV, POSE was on TV—there were trans editors at major publications. I remember, Meredith, when you were named the editor at a new Conde Nast publication. How could I go on and on about publishing not serving trans women, when, like, here’s Meredith at THEM? I would look out of touch! So, I thought about it and I took a chance at One World and Penguin Random House. They listened to me and they treated me well. Trans writing is in an interesting place—there’s the potential for a renaissance, and if I want to be part of that, it means getting my work into the hands of readers in the most efficacious way for a particular moment. Earlier it was free novellas, now I think it might be a big press.

MT: It is true that publishing has evolved and yet it’s also true that particular kinds of narratives still raise eyebrows even among the trans community. Detransition, Baby is coming at a time when the conversation around the “realness” of trans women is very much live with J.K. Rowling and her TERF crew. How do you see this novel in terms of those discussions that are going on right now?

TP: I remember that Toni Morrison said something like “the serious work of racism is distraction.” And something similar is happening with transphobia and the conversations of TERFs. The fight they want to have is a distraction. It is shallow. If I even acknowledge the terms they set, I walk into a distraction. Trans women are out here making really incredible art—I know so many trans artists doing mind-blowing things, making profound statements about what it means to be alive—and you’ve got this crew going “BATHROOM! TRANS! WHERE U GO POOPOOPEEPEE?” Or whatever they say. That is a distraction. Even as a fight, it is frankly a boring and undignified fight. I’ve got better things to do. I cannot control the conversations that other people insert Detransition, Baby into, but I can control my own participation, my own liability to be derailed by a bad faith distraction, you know?

MT: Right, absolutely, and the thing is that what makes those conversations so difficult are the imbalances of social power, and how cis women aren’t used to seeing themselves as oppressors, especially when they’re positioning themselves in relation to “former men.” One of the things that really struck me about Detransition, Baby is precisely this way that it’s very much a political book, but its politics are not immersed in the cis-centered conversations that the Twitter-Tumblr Industrial Complex, as you call it in your book, are having. I love how for the space of the novel it really does feel like the political fights are between trans women and the people who care about us. To what degree is that deliberate and to what degree does that just come out of your own unconscious?

TP: I see Twitter encouraging a particular type of politics. An attack or defend mindset. Fiction is a space for a different kind of mindset. A slower more meditative mindset which may still be political, but in a different mode. When politics are slower and more personal and there is less need for rapidly deployable defenses, I sink into my own way of seeing the world.

I know so many trans artists making profound statements about what it means to be alive—and you’ve got this crew going ‘BATHROOM! TRANS! WHERE U GO PEEPEE?’

I say things in this novel that I would never air on Twitter, and then I get to watch how those statements land with different characters. So it becomes very personal, very open. It was less a deliberate thing or an unconscious thing, just that I think fiction as a mode allowed me to not be anticipating my attacks and defenses. I could write a sentence or joke and know that no one would read it for years. And that space and time allowed for watching and feeling. And because my vantage is a trans vantage, that became the natural vantage of the book—I didn’t choose it for political reasons, but because it was simply the vantage from which I see, although that has political implications, of course. But the emphasis on that vantage arose from a mode of fiction that encouraged an impulse to share and see what happens, rather than an impulse to attack or defend politically. Long-form fiction has been for me, in the age of Twitter, a refuge of honesty and openness and even a different kind of humor.

MT: And there’s also this wonderful way that seeing something represented in fiction allows readers to be able to think through issues and actions that have a relationship to reality. For instance, with the central relationship of the two trans women in your novel (one who subsequently detransitioned), I just really love how messy Amy and Reese’s relationship is, and how you gave them so much space and complexity to both love and dislike and compete with each other. I wonder how you think of messiness operating in your fiction, and whether you think all types of trans messines are productive to depict especially to a broader audience or if there are some types that might be tougher? I was thinking actually of the scene where the characters see a poster for [the Laura Jane Grace memoir] Tranny and the narrative perspective criticizes it for not being helpful for trans women. Do you think of that as an instance of unproductive mess?

TP: Hmm. That’s an interesting question. I think for me to answer it, I’d like to define a couple of different sorts of messiness, because I think they work differently. When I wrote the book, I felt pretty emotionally messy, and that reflected in the characters—but in order to examine that messiness with clarity, I felt like I needed to figure out ways to write it in a technically orderly fashion. So writing their relationship was about finding orderly techniques and schemas to lay out their emotional messiness for examination. That process, the choice of how to order messiness, what to emphasize, and in what sequence, has, of course, political repercussions.

When the characters (somewhat separate from my actual feelings) lob a critique of the title “Tranny,” I think their complaint is that it’s not a technically orderly understanding of an emotionally messy word. The word was thrown at them in a jumble, with no context or order, no map for figuring out how it was meant. It was a technically messy deployment of an emotionally messy word. I prefer when people do the work to pair emotional messiness and technical clarity. Or at least some technique at all.

MT: Right. And it’s a different manifestation of trans as spectacle I think, especially when it’s performed for a broad audience. It’s wonderful that you brought up technique because even though I’m not particularly steeped in American minimalist fiction (Carver, Hemingway, etc.), my professors did try to indoctrinate me during my MFA.

I don’t know if you would agree, but there’s this wonderful way that Detransition, Baby subverts a particular kind of American domestic novel, which I haven’t read too much of but I’ve heard talked about in hallowed tones by many people, except that instead of divorce or alcoholism, the central issue is still the birth of a child, but one that involves a very different type of family than one would associate with such fiction. I know that you got an MFA at Iowa. Did that exposure affect the book and how or am I overreading even though you do refer to Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” hilariously in the book at a certain point?

TP: I think you are correct to feel that! I self-consciously wrote this novel as a bourgeois domestic novel in the grand American tradition. I don’t write minimalist sentences, and I like to think of myself as having a sense of humor, but otherwise, totally.

I saw the domestic novel as a place where artistic form and politics could meet up. Like, what happens when you write about the preoccupations of Franzen or Eugenides or whomever—and practitioners of the grand domestic novel certainly also includes women—Mary McCarthy or Elizabeth Strout or Annie Proulx etc—, only you put trans women at the center? What are the repercussions for basic domestic concepts like the nuclear family? Motherhood? Adultery? I think many readers don’t think of trans people belonging in those novels. But we have families, and often (given how many married men I know who have slept with trans women) those families are in fact the very same families as Cheever/Franzen/McCarthy families. We’re not actually siloed separately. It’s only in art that I see that siloing. So I was like, why not write them together as we all actually are? Using the same form in which families have historically been addressed in fiction?

MT: And I have to say, it was fascinating for me to also see how much the novel acknowledges the racial divisions within the trans community and how hard they are to get over. There’s this way that the novel circumvents a racial critique by being open about how tough it is for trans women and femmes of different races to be in community a lot of the time, in large part because cis, white supremacist society converges upon us differently and so our experiences end up being so different. Were you at all concerned about primarily depicting white characters given the plethora of issues surrounding trans folks of color?

TP: Yes, I am very concerned about issues of race in the trans community. But I think for me the question you’ve asked deals with what gets addressed inside the text and outside the text. Inside the text, I feel comfortable telling my story as a white trans woman. And in fact, I think most trans women of color are not that eager for me to attempt to represent their experience inside of my texts. They write their own stories and can represent themselves just fine without my help. The problem occurs when my story, as a white woman, becomes the story of “being trans” full stop. When my voice occludes other voices or represents them. This is obviously terrible for Black trans women and other trans women of color. But it is also terrible for me as a white woman writer. Because it means that I don’t get to be a bitch, or make jokes, or air dirty laundry—because those statements will all misfire. Making fun of trans white girls who feel sorry for themselves lands really badly when that same joke gets applied to black trans girls. It’s a question of ethics and politics, but it’s also a question of art. Me making white girl jokes which are also understood as applying to Black trans girls is most often simply bad art. The distinctions are necessary for the jokes to be good.

So the work I do on race occurs largely outside the text. The more other voices stand on a stage with me, the more my voice has the freedom to simply be itself. The more my voice is seen to represent simply my own idiosyncratic vision. Therefore, I won’t go on a panel which is made up of only white trans girls. I won’t read at a reading with only white trans girls. I try to help trans women of color get published. (Any Black trans girl reading this interview that might like a blurb from me—let me say it now: ask me, I will write you one). I do these things because I know some immensely skilled trans women of color, but also, because if their voices aren’t out there, my own white voice lands wrong: too loud, cumbersome, and arrogant. As a voice in a cacophony of published work, however, it lands well.

MT: And to a large extent we all have limited abilities as individuals to affect generations and centuries of minority oppression. Speaking of potentially oppressive tropes, one of the things that struck me reading the book is that the trans characters it depicts, including the two central characters, are for the most part attractive, even if they’re not always necessarily attractive according to established cis standards. I was wondering if that was something you thought about (it’s something I think about in my work) and I’m wondering if you think of that as in any way an issue to think through, and whether there can be more space to depict, not even ugliness, but ordinariness of appearance in trans literature?

I saw the domestic novel as a place where artistic form and politics could meet up.

TP: I agree with you. Some of my choices had to do with the genre I was working in: domestic bourgeois fiction. There are constraints to that. However, that is not to dodge the question by claiming genre as a defense. Often when I hear how people—including other trans people—speak about the attractiveness of a trans woman, cis-passability and attractiveness are deeply linked. That’s an incredibly complex linkage and one that is very emotionally fraught for me. It’s a painful thing to contemplate: trans people can’t see themselves as attractive on their own terms. I think I could write a whole book about that. There is so much to parse, and so much of that parsing is hurtful and requires care. When I address attractiveness, I would like to address it head on—and to do so in Detransition, Baby it would have hijacked a lot of the story. However, I would like to contemplate it, and soon. Actually, I have written some chapters of a story that takes on the question of passability and attractiveness. A Western! But since Detransition, Baby is merely my debut, I don’t think that I yet have the eminence necessary to be a writer who charmingly contemplates in interviews her unfinished works, and I’ll stop there. Suffice to say, I hope I get a chance to write more books!

MT: I’m confident you will! Okay, last question: It strikes me as we’re discussing these questions of attractiveness and relationships between trans women that your book also discusses how hypercompetitive we can be and how so many of us did not come into our transness with any meaningful mentorship (I certainly didn’t). I went through a semi-stealth phase when I didn’t hang out with trans women for a while, and then emerged from it in 2014 with a sudden sense that the climate had changed while I was away, that there was much more of a culture of mutual support and trans women being really happy for each other’s accomplishments, etc. I was wondering what your experience has been around those issues and also who were some of the trans folks who helped you along your path to being the fantastic author you are.

TP: In 2014, I met Casey Plett, Sybil Lamb, Imogen Binnie, Morgan M Page, Jackie Ess, and other writers in the Topside orbit. That scene totally imploded. However, I think they articulated an ethos that lived on after. Roughly, that ethos is just what people now call t4t. Topside people didn’t call it that, the word arose a little adjacent to it (in literature, and for me personally, I think T Fleischmann) but I think the Topside social scene articulated the contours of the concept extremely well. They addressed how most problems we have as trans women aren’t unique or special to us as individuals, and that any of us isn’t likely to be the first person to think about how to solve those problems. That actually, confronting the problem of how to live as a trans woman needs to be a group endeavor in the most concrete, non-abstract sense. It’s a series of logistical solutions that we can just hand to each other, and that can’t be compiled by any one individual. Although in literature, one individual author can write the vibe or context. The context being the collective knowledge of a group. Go to this clinic. Hang out at this bar. Buy this kind of jacket. Do your makeup like this. Don’t talk shit about each other in these ways. Avoid this kind of man. Etc. etc. Like, basically, spare yourself the pain of making all our mistakes. Let us be negative role models for each other. And then, when we were negative role models for each other for long enough, we became positive role models for each other.