If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

From LOLITA IN THE AFTERLIFE, edited by Jenny Minton Quigley. Reprinted by permission of Vintage Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Essay copyright © 2021 by Robin Givhan. Compilation copyright © 2021 by Jenny Minton Quigley.

The image of Lolita embedded in our memory is not the Lolita of Humbert Humbert, but the idea of her as etched by a fashion industry obsessed with nubile femininity.

When we think of Lolita, we see baby doll dresses, Peter Pan collars, tartan skirts, and insouciant pouts. We see long-legged, gangly young girls in short skater skirts who are a wind gust away from indecency. We see adolescents costumed in billowing evening gowns sashaying down international catwalks—rosy-cheeked representatives of an industry engaged in a billion-dollar game of dress-up and make-believe.

Lolita is both a noun and an adjective. Lolita is both oppressive and freeing, exploitative and exploited. Lolita is complicated.

With the rise of the Youthquake movement in the 1960s, the modern fashion industry first embraced Lolita as a style icon. Youthquake, coined by editor Diana Vreeland and defined by miniskirts, model Jean Shrimpton, and the music of the Beatles, originated in England but was of a piece with the hippies and the don’t-trust-anyone-over-thirty ethos that took hold in the United States. Fashion turned its attention to the massive impact of a generation of fresh-faced baby boomers, with their cultural influence and their buying power. Before then, youth was not so much an exalted state as it was a rite of passage.

Before Youthquake, there really wasn’t much of an adolescent style—not a codified one, at least. A girl went from childhood, through a brief period of teenage angst, before turning into a miniature version of her mother.

Lolita is both oppressive and freeing, exploitative and exploited. Lolita is complicated.

In fact, the baby doll dress, which has come to represent impish sexuality, was popularized in the 1950s by Cristóbal Balenciaga—that most sophisticated of Paris’s couturiers. At the time, it was hailed as an empowering frock, one that freed women from the constraints of girdles and corsets. But the 1960s turned the baby doll dress into something else entirely. When it was worn by the era’s iconic model Twiggy, with her scrawny frame and doe-like eyes, the dress’s message became more complex. It was feminine freedom enmeshed in youthful rebellion and the sexual revolution. Young women were laying claim to their personal agency, and that included the pleasures

of sex.

In the ’90s, young women used the baby doll dress for subversive purposes. Alternative rock performers such as Courtney Love embraced it as a counterpoint to the accepted narrative about women, power, propriety, and sexuality. If the culture insisted on infantilizing women, on treating them like lesser humans, performers would turn the symbols of girliness upside down. They took to wearing all manner of babyish gear while spewing profanities and declarations of strength into a microphone.

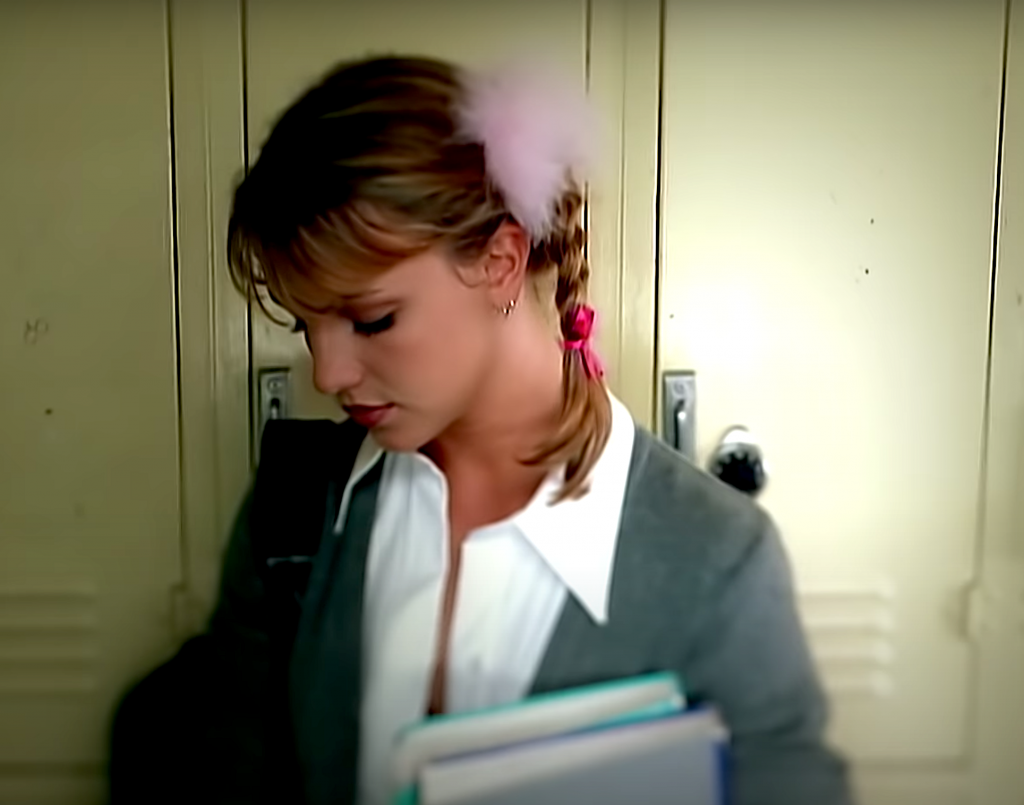

The popular culture of the ’90s painted Lolita as knowing, as self-aware—rather than as a victim. Lolita the feminist. She is not the innocent schoolgirl; she is the manipulative one. She is Britney Spears in a modified school uniform—mid-thigh pleated skirts, midriff-baring white shirt, gray cardigan, blond pigtails, and more makeup than a drag queen—wielding an invisible whip in a dance video as she sings the yearning lyrics from “. . . Baby One More Time.”

My loneliness is killing me (and I)

I must confess I still believe (still believe)

When I’m not with you, I lose my mind

Give me a sign

Hit me, baby, one more time.

If Madonna used her adult sexuality as a powerful, feminist provocation, then this early version of Spears announced that young girls have sexual yearnings that are both natural and volatile. If we consider a young girl as a full person, those desires should be addressed head-on instead of covered up, dismissed, or admonished. Spears was speaking to her young fans in a way that they understood and appreciated, but she was also exploiting the stereotypes promulgated by the male gaze. Lolita, when taken up by adult women as a public identity, can be a declaration of strength. The fascinations, frivolities, and lusts of girls deserve consideration and respect.

In Japan, Lolita girls costume themselves like Victorian dolls—like hyper-feminized children. Their play on identity

comes out of a fascination with cute culture. They eschew grown-up sexuality and the way it demands that most every aspect of their physical being be sexualized. Japan’s Lolitas situate themselves outside the realm of adulthood, using giddy girlishness as armor. When they take on this identity, it’s hard not to view them as hiding in plain sight, as hiding from the complex beauty of their own sexuality. They have ensconced themselves in another time, another age. They are giving themselves an opportunity to simply be.

Lolita, when taken up by adult women as a public identity, can be a declaration of strength.

We can’t see ourselves in a vacuum; it’s always juxtaposed with the way in which we are seen by the world. And so there is a powerlessness in the Lolita archetype, too. She is the naive child stalked by a predator, the child whose innocence has been snatched away. Recall the Calvin Klein Jeans advertisements from the mid-1990s, when adolescents were sprawled on the floor of a wood-paneled rec room. The models stared glumly into the camera, their legs akimbo—giving the viewer a glimpse of their underpants. What separated a scene of child pornography from the so-called artistic depiction of the rebelliousness of youth? Answer: A Justice Department investigation that found all the models were of age.

I have always viewed the Lolita archetype from a distance. I didn’t envy her preternatural body confidence. I didn’t wring my hands over the sexualization of her ruined innocence. I certainly never dressed up like Lolita for a Halloween party or attempted to channel her luminescence during the years when I was feeling my way toward maturity. Lolita was never a part of me mostly because she was not portrayed as Black or brown—like me. She was pale with knobby knees and rosebud lips. She was a character as disconnected from me as Snow White.

Lolita was verboten. She was not written within the context of what it meant to be a young Black girl. The culture does not see Black girls as having a fragile, dangerously irresistible beauty. And if a nymphet of color is boldly manipulative with her sensuality, willing to flaunt it with a devil-may-care attitude, she is seen as liberating herself as much as playing into historical tropes about oversexualized Black bodies. She isn’t viewed as an icon; she is a scourge.

Race is intertwined with the cultural interpretation of Lolita. She is debated and dissected because her particular beauty is valued. And the greater the value placed on it, the more I am reminded of how brown-skinned girls are discounted.

Lolita is an expression of whiteness just as surely as she speaks of youth, gender, and sexuality.

Fashion’s iterations of Lolita force a conversation not just about the way in which we treat children, allowing them—

impelling them—to grow up more engaged with a salacious world. We fetishize their immature physiques: their hipless silhouettes, breasts that are mere buds, tummies so flat as to be nearly concave. That is the shape that defines womanhood, and to grow beyond that is to grow beyond desire.

Lolita is the vehicle by which fashion truncates childhood.

Lolita is the vehicle by which fashion truncates childhood; it’s how fashion feeds off the loose-limbed lightness of youth, hollowing it out. And yet, fashion’s obsession with Lolita is detrimental to adulthood, too. It transforms adulthood into a state of stultifying obsolescence.

Lolita has 30-year-old women considering cosmetic surgery and 20-year-old women relying on social media filters to make their self-portraits more palatable. Adulthood is a kind of purgatory. Youth is a fleeting marvel.

Lolita is the emblem of one of the many style tribes that connect us around the globe. She shape-shifts based on context and consciousness. She is a reclamation of girlhood in all its complexities. She is a destroyer of innocence. She slays. She is a victim. She is fashion.