WASHINGTON — NASA’s Mars 2020 spacecraft is operating “perfectly” ahead of its Feb. 18 landing on Mars that will be a key milestone for the agency’s future Mars exploration plans.

The spacecraft is scheduled to land the rover Perseverance on the surface of Jezero Crater on Mars at about 3:55 p.m. Eastern Feb. 18. That time is when the signals from the spacecraft arrive on Earth based on a light travel time of 11 minutes and 22 seconds from Mars.

At a Feb. 16 briefing at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, project officials said the spacecraft was on course and operating well ahead of its crucial entry, descent and landing (EDL) phase minutes before touchdown.

“Perseverance is operating perfectly right now, and all systems are go for landing,” Jennifer Trosper, deputy project manager for the mission, said at the briefing. Controllers sent on Feb. 12 the “DO EDL” command to the spacecraft, triggering a series of activities on the spacecraft to prepare for the landing.

While there is still the ability to adjust the spacecraft’s trajectory if needed, Trosper said that Mars 2020 is on track to land in Jezero Crater as planned. “The targeting is on the bull’s-eye, and we are headed exactly where we want to be for Mars,” she said.

Mars 2020 will use a landing system similar to that used by Curiosity, the rover that landed on Mars in 2012. That system does include some improvements, notably a technology called “terrain relative navigation” where the descending spacecraft takes images of the surface below and compares it to an onboard map, using that information to guide it to a safe landing zone.

Telemetry from Mars 2020 will be transmitted back to Earth during EDL through a “pseudo bent pipe” relay provided by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter spacecraft. That will provide the most data through landing, Trosper said, including the possibility of images from hazard cameras on the front and rear of the rover immediately after landing. The spacecraft will also transmit a series of tones directly to Earth in X-band during descent, providing information on key mission events.

Another orbiter, Mars Odyssey, will pass over Jezero Crater about three and a half hours after landing that will provide information on the status of the rover. “Getting that pass would give us a lot of information about the state of the vehicle,” she said. The European Space Agency’s ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter will fly over the landing site a few hours after Odyssey, also with the ability to relay data from Perseverance.

“If all goes well, we could potentially see some images by the end of the day,” she said. “If not, it’s possible that something happened that maybe caused the vehicle to go into a safing mode after landing.” In that event, it could take several days to correct the issue and restore normal operations.

Perseverance itself is superficially similar to Curiosity, but with a new set of instruments and other upgrades, such as wheels that are strengthened after those on Curiosity were damaged by sharp rocks on the Martian surface. “Percy’s got a new set of kicks and she is ready for trouble on this Martian surface,” said Adam Steltzner, chief engineer for Perseverance.

Scientists will use the instruments on Perseverance to study the planet’s past habitability, including any evidence of ancient microbial life there. A major aspect of the mission, though, is to collect rock samples for later return to Earth as part of the overall Mars Sample Return program.

Mars Sample Return, which includes two missions launching no earlier than 2026 in cooperation with ESA to collect the samples cached by Perseverance and return them to Earth, accounts for the nearly all of NASA’s Mars exploration activities in the coming decade, beyond operation of existing missions. A failed landing by Perseverance would upend that strategy.

“It’s not adding stress,” Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said of the implications of the Mars 2020 landing on Mars Sample Return. “We’re entirely focused on one thing right now, which is the successful landing.”

Trosper said Mars 2020 is the fifth Mars landing she’s been involved with. “The team has been doing a great job. The spacecraft is solid,” she said. “There are no guarantees, but I’m feeling great.”

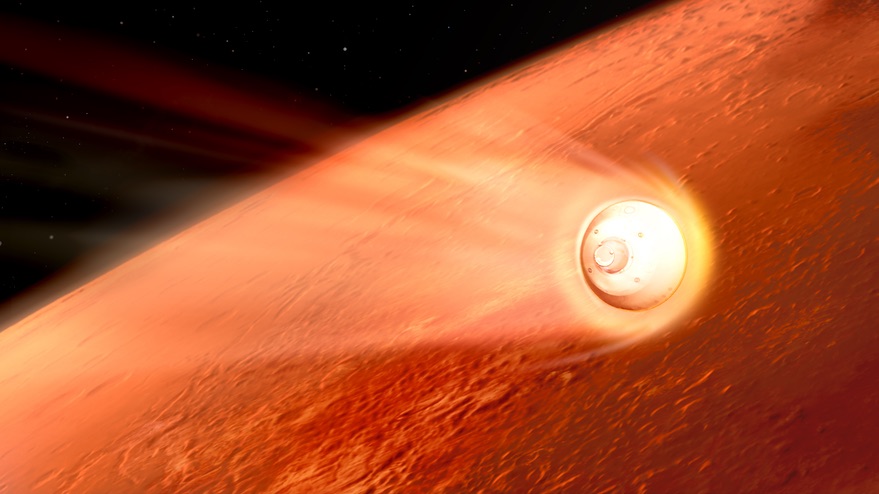

In 2012, NASA famously called the EDL phase of the Curiosity mission the “seven minutes of terror,” referring to the time from when the spacecraft encounters the Martian atmosphere to when it lands, and all the hazards during that time that could doom the spacecraft. The agency is once again using the “seven minutes of terror” phase for the Perseverance landing, even though some involved with the mission think “terror” is perhaps a bit overwrought.

“Probably ‘terror’ is not the right word,” said Rob Manning, chief engineer at JPL and a veteran of past Mars landings, during a session of the Planetfest ’21 conference held by The Planetary Society Feb. 14. “It’s probably more like anxiety: deep, deep, deep anxiety.”

“When you see us cheer” after a successful landing, he added, “it’s not happiness. It’s relief, deep relief.”