A short story collection of queer Gen Z women in Michigan navigating their twenties. A novel about an Irish woman in Copenhagen who receives an unexpected visit from an ex from her pre-transition life. Stories following the hopes, dreams, and struggles of a group of Black queer and trans friends in Montreal. A novel exploring how a relationship between two gay men in London changes when one of them comes out as a trans. And a work of fiction set in a municipal dumpsite on the El Paso-Ciudad Juárez border that interweaves the lives of three very different women. These 5 books are the finalists for the 36th Annual Lambda Literary Awards‘s Transgender Fiction Prize, taking place on June 11th.

Centering trans characters at the heart of their work, these writers explore questions of identity, race, and gender. Whether in Kuala Lumpur or New York, the tie that binds these books together is the quest to find love, acceptance, and belonging in a world that’s hostile towards their very existence.

We talked to finalists Emily Zhou, Valérie Bah, Soula Emmanuel, Sylvia Aguilar Zéleny, and Nicola Dinan about their books, their path to becoming a writer, and their trans literary influences.

Emily Zhou

Tell us about your path to becoming a writer and publishing your book.

I joined The Michigan Daily as a junior in college and wrote a few dozen essays, reviews, and pieces of criticism for the arts and culture section, and gradually realized I had taught myself how to put together a coherent piece of writing. After I finished school, I tried my hand at writing short stories and put them on a Substack newsletter for a few friends and people on the internet to see. When LittlePuss Press got started, the poet Stephen Ira nudged me to submit what I had written so far as a partial manuscript, and to my complete surprise they accepted it. In the subsequent two years, I vastly reworked the stories I had already written and wrote the remaining stories.

Tell us about your book.

Girlfriends is a collection of realist short stories mostly about trans women in their early to mid twenties. It’s set in Ann Arbor, Michigan (where I grew up and went to college), and in New York City (where I have lived since 2021). My goal was to depict life in these places in a naturalistic but forgiving way, and show how young trans girls make their ways through social worlds that uncomfortably and incompletely accommodate us. Most of my characters are a few months to years into gender transitions that coincided with broader coming-of-age points in life, and are usually engaged in figuring out what to do next and experimenting with their senses of self. It’s a chatty book, light on plot, mostly pretty understated with a few moments of heightened emotion and drama.

What books by trans authors have been influential to you and why?

One of the things that made me want to write fiction was my discovery of Topside Press’s catalog. In college I read a lot of queer theory, and I had become accustomed to primarily looking at transness as a sociopolitical phenomenon, examined from the outside. The Topside writers wanted a different way to write about trans people—not merely “telling our own stories,” but making art out of them and in so doing asserting agency over the domain of culture. In particular, Casey Plett’s book A Safe Girl to Love made me realize that I had something to say. (Casey later became the editor of Girlfriends at LittlePuss.) Her stories have a sort of understated, resonant emotional depth that I still aspire to in my own work, and they’re closely focused on the meaning locked in ordinary experience, memory, and friendship. I continue to learn a lot from her work.

When I moved to New York I came to understand that there was a much wider world of experimental trans writing that had sprung up after Topside folded. One of the books that people told me to read was hannah baer’s memoir Trans Girl Suicide Museum, which made a big impression on me. Close to the beginning, she writes that she isn’t trying to write a “good book” or polish her thoughts to make them more coherent and digestible, and I think the spontaneous, thinking-out-loud quality the book has works in its favor—it feels like having a long, freewheeling conversation with a particularly intelligent and sensitive friend. (And despite what she says, there are some jaw-dropping, bravura passages in it.) In Girlfriends I was frequently trying to capture the quality of in-the-moment thinking and processing (particularly in the final story, “Gap Year”), and I took a lot of cues from baer’s book.

Soula Emmanuel

Tell us about your path to becoming a writer and publishing your book.

I wrote Wild Geese during Covid, in 2020 and 2021, so it has the pensive and slightly claustrophobic feel of that time, when we couldn’t see each other but it also felt like the world was about to change. I was feeling slightly stuck between two versions of myself then, between the part of me that wanted to change and the part of me dominated by anxiety—all of that is reflected in the novel. Then things moved quite quickly: I won a mentorship place with a literary agency in the U.K. in 2021, and the book was published in 2023, so, ever the anxious person, I didn’t quite have time to have second thoughts about it.

Tell us about your book.

Wild Geese is about a trans woman, Phoebe, who has moved from Dublin to Copenhagen and is about three years into her transition. One evening she is visited by Grace, her ex from before her transition, who shows up unexpectedly at her door. They spend the weekend together, weaving their personal stories into the streets and old buildings of Copenhagen, and it becomes an exploration of how people change, how we can run away from our pasts and how we carry with us different versions of ourselves. It’s kind of a twist on the old Irish emigrant story too: instead of the main character going home, home comes to them, in a very 21st-century way. It has been compared to a trans Before Sunset, which I think is pretty accurate!

What books by trans authors have been influential to you and why?

My favourite trans novel is Little Blue Encyclopedia (for Vivian) by Hazel Jane Plante—a former Lammy winner in this category!—and I love the way she interplays transness with other topics like grief and fandom, to bring out the humanity and nuance of her characters. I also love the writing of Juliet Jacques and Garielle Lutz.

Valérie Bah

Tell us about your path to becoming a writer and publishing your book.

Franky, I’ve had exceptional support! My path to publication started with a fierce ass literary collective and collection called “Les Martiales” conceived by Stéphane Martelly, a poet, scholar and painter who assembled a community of Black women and femme writers. Honestly, she’s doing the Lorde’s work in a very white literary landscape in Québec.

Also, shoutout to Metonymy Press, a small gay publisher co-founded by Ashley Fortier and Oliver Fugler, who hosted the translation by the artist Kama La Mackerel, who so generously envisioned bringing the book to an anglophone readership.

Tell us about your book.

The Rage Letters, translated by Kama La Mackerel, explores the intertwined lives of a group of four Black queer and trans friends living in a Montrealish city. it’s also an experiment in narrative structure, tracing the patterns of their lives through cross sections of their joint experiences. Also, in the original version, I had fun circumventing the conventions of literary French.

What books by trans authors have been influential to you and why?

Love me some Awkaeke Emezi for their unapologetic voice and cosmology. We should all be so daring. Honestly, it was a game changer for me to see them doing their thang. Also, Kai Cheng Thom’s Fierce Femmes and Notorious Liars (also published by Metonymy!) is so real and precious as an intricate love letter to her younger self. That’s very much how I approached The Rage Letters.

Nicola Dinan

Tell us about your path to becoming a writer and publishing your book.

I don’t think I gave myself permission to call myself a writer until I started writing Bellies—a mistake! I’d always loved writing, but never felt “qualified” enough to write a book, until one day I did. The first draft of Bellies came together in seven months, and after another six months of editing I found an agent, and a few months after that there was a book deal on the table. Looking back, it feels like I wrote it in a flurry and with a real sense of urgency—maybe because I hated my day job and loved writing, or maybe because I was scared that there were a million other people with the exact same idea. I write a bit more sensibly now.

Tell us about your book.

Bellies is the story of Tom and Ming. Tom’s an awkward white boy who had a privileged upbringing in South London (though he’ll do his best to hide it), and Ming is an ebullient playwright from Malaysia who struggles with OCD. They meet at a university drag night and fall quickly in love, as you do when you’re twenty, but when they move to London after graduation to start the next chapter of their lives, Ming comes out as a trans. A relationship seemingly between two gay men becomes something else, and Tom and Ming have to negotiate what that means for them, and where their love for each other goes.

It’s a story about a relationship facing a potentially insurmountable hurdle, but it’s also a novel about the mess of being in your early twenties.

What books by trans authors have been influential to you and why?

I wish I had more trans authors to list, but through my own failings, and maybe more critically those of mainstream publishing, I lacked exposure to a wide set of trans authors to draw inspiration from. Detransition, Baby was influential in the sense that I strongly believe it has made the publication of books like Bellies more possible.

In the lead up to and since publishing Bellies, I’ve read so many more trans authors who inspire me. K. Patrick, Jordy Rosenberg and Kai Cheng Thom, to name a few.

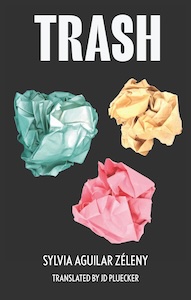

Sylvia Aguilar-Zéleny

Tell us about your path to becoming a writer and publishing your book.

I started teaching literature for high school students in the early 2000’s, I had always been an avid reader and, I guess, a storyteller. I liked writing short-stories and would publish some here and there back in Mexico, where I am from. Becoming a writer was not something I was pursuing, I like believing is something that happened to me, something that I started doing as a need to put my creativity (and my anxiety!) to work.

I moved to El Paso in 2010 to do my MFA, and the program but most importantly, the life at this border gave the tools, the space, and most importantly, the motivation to write this novel. It was first published in Spain with Tránsito Editorial, but I knew I wanted to see it in English with Deep Vellum, I admired their catalogue and their work; they sorta knew me because of The Everything I Have Lost, a novel I wrote in English and published with Cinco Puntos Press. Deep Vellum proposed JD Pluecker to translate this book, and it was the best decision ever because JD had long conversations with me and involved me in the process in more than one way.

Tell us about your book.

Trash interweaves the experiences and voices of three very different women whose life or work moves around the municipal dumpsite of Ciudad Juárez, México. A teenager orphan who has always lived and worked at this place, a scientist who is researching the site, and a transwoman who manages and cares a group of sex-workers become the protagonists of this attempt to observe the complexities of survival, love, violence, at the Mexico-U.S. border.

What books by trans authors have been influential to you and why?

I read Las Biuty Queens by Iván Monalisa Ojeda, a short-story collection/episodic novel when I had the first draft of Trash. My novel is all about voice and characterization and Ojeda does a great job in recreating the life of the cuir latina community in New York.

Trans: A Memoir by Juliet Jacques is probably the first memoir I read about a transwoman, it is a coming of age that brings attention to the loneliness, the struggle, and the violence trans and in general LGBT + community endures; but at the same time, it is an example of love, resistance, and community.

Read the original article here