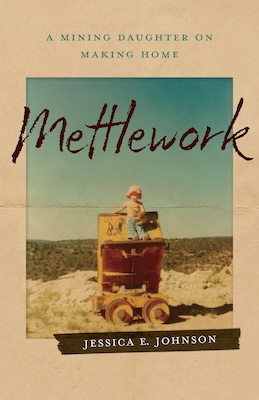

In her memoir, Mettlework: A Mining Daughter on Home, Jessica E. Johnson writes “a story that has room for men who get things done” and “women who make-do and ask for little.” It’s a story about growing up in various mining camps, interwoven with her transition to parenthood in post-recession Portland, Oregon. But at its heart, it’s a story about motherhood, what is means to create a home, and what society determines valuable.

In Johnson’s world, hard tangible things like gold and silver held value; thus, her family made homes around these things. More abstract things like caring for others and making a home comfortable—things Johnson’s mom did and what Johnson does for her children many years later—come secondary.

When an archive of her childhood arrives via email from her mother during the early weeks of postpartum, Johnson begins to see how the bedrock images of her isolated upbringing have stayed with her.

Married to a third-generation Alaskan fisherman, having uprooted myself to live with him and relinquished my career to raise our children, I saw parallels between my life and the narrator’s mother. Reading this book felt very resonant as I reflected on my contributions, both inside and outside the home, and the worth of motherhood in a capitalistic world.

Summer Koester: What was it like to pour over your mother’s letters during her times in the mining camps—places without help, running water, and help—while you were just a few weeks postpartum?

Jessica E. Johnson: Growing up and in my twenties, I had a lot of ambivalence about being a mom, and even after I knew I wanted a family of my own, I carried that uncertainty with me. There was less public writing then about ambivalent motherhood, and I sometimes felt freakish in my feelings and unsupported as my actual self in my actual circumstances. My mother’s letters opened a window onto the past-before-memory; both what happened, and a sense of my mother’s account taking shape. I sensed that some of the contradictions I was experiencing were set up by the past and the narratives I’d received about it. I had an inkling, too, of the ways in which the life into which I was born was emblematic of larger social narratives. The experience started me down this path of investigation that became Mettlework.

SK: So much lip service is given to mothers who sacrifice their careers to stay home and raise children. But when the rubber hits the pavement, we live in a capitalist society, and there is no capital in mothering. Most do not consider parenting “work” and, therefore, it deserves no compensation.

You write, “A different currency is required.” Can you elaborate on that, or what another currency would look like?

JJ: I used the word “currency” there because I’d been working with this language of metal and capital throughout the book, but in fact I’m a socialist, and I think the real answer to this question is working toward a society (or many small ones) with the capacity to value land and people and plants and animals beyond their ability to be exploited. To me, the call for a new currency in this passage is the simple recognition that the current form of capitalism reaches into every part of life and fails to value that which is most precious. This is a simple thing to know and not an original insight on my part but still a difficult thing to live with here and now.

The current form of capitalism reaches into every part of life and fails to value that which is most precious.

There are large-scale policy changes that would make a huge difference in perception of value, things like the right to healthcare, housing, and a fully funded education, and the orientation of all of these away from profit and toward the idea of widespread and balanced thriving into the future. Some low hanging fruit might be decent parental leave for both parents and something like an expanded child tax credit.

However, value is a social proposition, which means people can always create some sense of value simply by recognizing each other and fostering the spaces in which recognition is possible. Inclusive literary and learning spaces are important to me for this reason. So are the writer-mom text threads that get me through day to day.

In your question, I also note the ways in which naturalism and gender attach to carework. The idea that gestating, birthing, and raising children is a matter of instinct and nature for women, is an idea that has made the biology and labor of pregnancy, birth, and childcare invisible. One can see this in public discourse about abortion: educated people are deeply ignorant of many basic obstetric and gynecological facts. I want to think this mythology can change, first through awareness.

What does it mean to recognize and value the work of raising people—or the work of study, or of art-making—in the communities where we have the most influence? In individual workplaces? In friend groups? In families? Recognition and re-valuing can start anywhere. And part of change might be simply the awareness of living in deep contradictions.

SK: You write about pursuing a “workmanlike identity” that might “feel masculine and purposeful.” How does pursuing such an identity square with the role of mothering that you are naturally drawn to? How do you reconcile your role as the self-sacrificing, virtuous mother similar to the one depicted in your mother’s handbook for mothers and that of financial contributors?

JJ: When I was younger, I was definitely more drawn to the workmanlike identity–it was the primary, consequential role in the very small places where I grew up, and I think people who know me might say I still carry some of this identity.

As union members who work in the same (public) sector, my husband and I have generally maintained balance in the earning and caregiving. Membership in a union has been crucial to my ability to do this, and even to occasionally flex toward writing or additional caregiving when necessary. This is why I have thanked my local in both of my recent books–without the contract and its provisions and protections, I’m not sure I could have written them.

In Mettlework I was attempting to walk a difficult line: of reckoning with the internalized misogyny in my own desire not to become a mother like my own mother, but also thinking about the construction of the mythology around (white) maternal virtue and creative self-sacrifice. How much of this self-sacrifice is inherent in parenthood, how much is a deeply problematic myth that upholds the colonial family, and how much is reinforced by laws, policies, and practices? In my own thinking, I acknowledge that some elements of this problem are probably in the nature of being a parent, while trying to stay aware of myths that can be exposed as such and structural forces that can at least theoretically change.

As one example, as a wealthy society, we could have a functional childcare system that allows parents to work if they want to and children to thrive and childcare workers to be paid decently. This is possible, though perhaps politically far-off. But there are also smaller scale and interpersonal ways for everyday people to begin undoing this knot in which having children means diminished public participation.

In my own life, I think I reconcile these roles by recognizing that the gendered splitting of capacities in the nuclear family structure is ultimately not something I want to reproduce.

SK: You write: “Everything would work out, she was saying, if I could be endlessly fluid, endlessly gentle, addressing my needs by finding a way to need less.” Then you add, “Things would be fine if–for the first time—I could find a way to be more like her.” How has that belief shaped the way you parent and exist in the world?

Taking care of people is a form of expertise rarely recognized as such because the scale is small and because it has been seen as women’s work.

JJ: In that passage, I’m trying to figure out the diaper question—what kind of diapers to use—which stands for the larger question of how to fit the baby into lives already complicated by art and illness (two time- and energy-consuming factors that don’t pay). In this moment, I’m deeply resisting the idea of making things work out by giving up my job and sort of living in the moment like my mother did. In fact, I continued to resist, though I had some reprieve in the form of job-sharing periods (when I wrote much of this book, and another). I have been harder edged than she was. I insisted on maintaining some boundaries around a sense of what I need to do, both as a worker and as a writer. This has not been easy. Like many women I know, and men who take hands-on parenting seriously, I often feel torn apart by competing demands. On the other hand, I think it was pretty much impossible for me, personality-wise, to do what my mother did, and I’m sure that would have been profoundly challenging in other ways.

SK: Either by choice or expectation, your mother asked for little and managed with less. Later in the book, you describe how fish sacrifice their lives to reproduce:

“They keep going, I thought. Their bodies start to decay while they’re alive. They keep going. They are a vehicle for the next generation and nothing more and it’s okay. They change and change and change and then they die.”

What parallels, if any, did you see between your experience as a mother and your own mother’s?

JJ: I remember having some moments early on in which I had the sensation of inherited memory, the sense of what women before me survived. Each of us here is here because of a chain of women giving birth and raising people in what had to have been incredibly hard circumstances.

It was important for me in writing this book, even as I’m looking hard at the social role she occupied and some of the ways she made sense of her life, to honor my mother’s labor, her writing, and just who she is as a person. I hope to have done that. I wanted to reckon with the situation I was born into. At the same time, I felt that disavowing this past completely would be–ironically–a way of reproducing it. It’s easy to say, “that’s not me,” but something in that move reminded me of my parents’ unquestioned practice of picking up and moving on from one mine to the next, forming minimal relationships with the places they were.

One connection to my mother—though maybe not a parallel—is that she created and preserved this home that was often a place for wonder, creativity, and rest. She could do that by keeping a kind of mental barrier between the household and the outside world, an avoidance that I believe caused me harm. In writing this book, I sometimes came to think of the work I have tried to do in public–especially in my teaching–as a way of bringing the acceptance she showed me outside the family unit and into an open-access educational space. I have made different choices than she did; I also wouldn’t be able to do anything I do without the benefit of her responsiveness and care.

Possibly a more direct parallel is that the unpredictability of my husband’s illness sometimes requires of me a kind of responsiveness that is not unlike my mother’s. She had to shift according to the mine and my father’s career, and I often have to shift and scramble according to the health needs of my partner and children.

SK: In one passage, you are talking to your daughter and say: “I can’t watch you dreaming around the house and forest, talking to trees, embracing your brother, twirling for the sake of twirling, without remembering all the forces, outside and ahead, that will work to separate you from yourself, that will whisper that your beauty can be measured according to a standard, that your body can be ignored, that your time and brain are without value except as the means for someone to accrue profit, that your ability to see and hear and care for others is, at best, worth minimum wage.”

There are so many things to unpack here. Why do we undervalue caring for others? How do we evolve from attaching a price tag to our worth? How do we begin to value more intangible things like caring for others? Can we?

JJ: In this part, I’m stating my determination to pass on a worldview different from the one I inherited, a way of looking at things that could sustain my beloved child, even in an uncertain future. I was thinking that might mean a sense of herself that would keep her whole despite all she might encounter.

Part of that worldview requires putting care at the center. Taking care of people, holistically, in an intimate way is a form of expertise rarely recognized as such because the scale is small and because it has been seen as women’s work. I conjecture that this has to do with centuries of misogyny and probably colonialism—but I’m just a poet. Taking care of oneself is maybe undervalued, too. Society is structured in ways that often require people to override or ignore basic needs and make real care very difficult to get. I wanted everything good for my child, and as parents do, I considered the fact of her miraculous. Her being was (and is) precious to me. And while of course change begins the moment a person is born, I wanted to pass on an account of the world in which life–including her life–is in fact precious.

I think we evolve from attaching a price tag to our worth in social formations that can recognize non-monetary value and engage in resistance to notions of purely market-based value. Resistance can mean many things. Not everyone has the same options when it comes to activism. And political situations are always fluid, so the forms of resistance should be too. However, I see this question of value as fundamentally a social one. We can value care in community and as an act of resistance. This sounds super serious, but to me this is also about laughing for real and seizing joy where you find it and feeling greeted and seen and known–and being able to take more risks because you know there are some people who have got you.

When I think about everything I just said in relation to my mom’s life, I note that her physical isolation often made community very difficult. Still, I see it as almost impossible to do much of anything alone.

Read the original article here