My Cartoon Turtles Say What I Feel

“Laramie Time” by Lydia Conklin

Maggie and I had been living in Wyoming for three months when I finally agreed we could get pregnant. We were walking on a boulevard downtown over snow that was crunchy and slushy by turns, heading home from a disappointing lunch of lo mein made with white spaghetti. The air was so sharply freezing, the meal churning so unhappily through our guts, that I longed to cheer the afternoon. I’d made up my mind the week before, but I didn’t find the right moment to tell her until we were trudging through uncleared drifts in front of the former movie theater. The Christian who’d bought the place for nothing had arranged the plastic letters into rhetoric on the marquee: GOD IS LISTENING GOD KNOWS YOURE ROTTEN.

“Maggie,” I said, taking her hand. “I’ve decided.” Last week’s test results had exposed her declining fertility. If we wanted to do this, it had to be now.

She aimed her freckled stub nose at me and studied my face. “Where to get dessert?” She spoke bluntly, the joke of what she really hoped in the deadness of her words.

“I want to have a kid with you.” I meant the words to sound natural but invested with meaning—inflected emotion on kid and you—those two words the sum total of my future reality. But the sentence bumbled out, awkward, half-swallowed.

“Amazing.” She spoke flatly, her unseasonable tennis shoes sinking into the slush. Why was she speaking flatly? Maggie had begged me for a kid for years. She should’ve jumped into my arms when I agreed. She should’ve fucked me right there on the boulevard, even though it was winter in Laramie, even though we’re lesbians and fucking wouldn’t help with getting the kid.

“Aren’t you happy?”

A tear occluded one eye, but she squeezed it to a slit, squeezed both eyes closed. When she opened them, they were clear and dry. “Thank you. I am happy.” She sounded mechanical. But sometimes she was like that—a sweet logic robot. She waited until we stepped onto the curb on Custer Street to clamp me in a cold hug.

That was it. After five years of debate. After crying and threatening to leave, after pointing out every child, even lumpy ones, after invoking hormones and decreased viability and geriatric pregnancies whenever worry or resentment surged through her. Not to mention last week’s meltdown over the test results. And now look at her, unsurprised. Maybe she figured I wouldn’t have moved across the country to spend a year deciding not to have a kid with her. But I was unpredictable and stubborn. She knew better than to count on me.

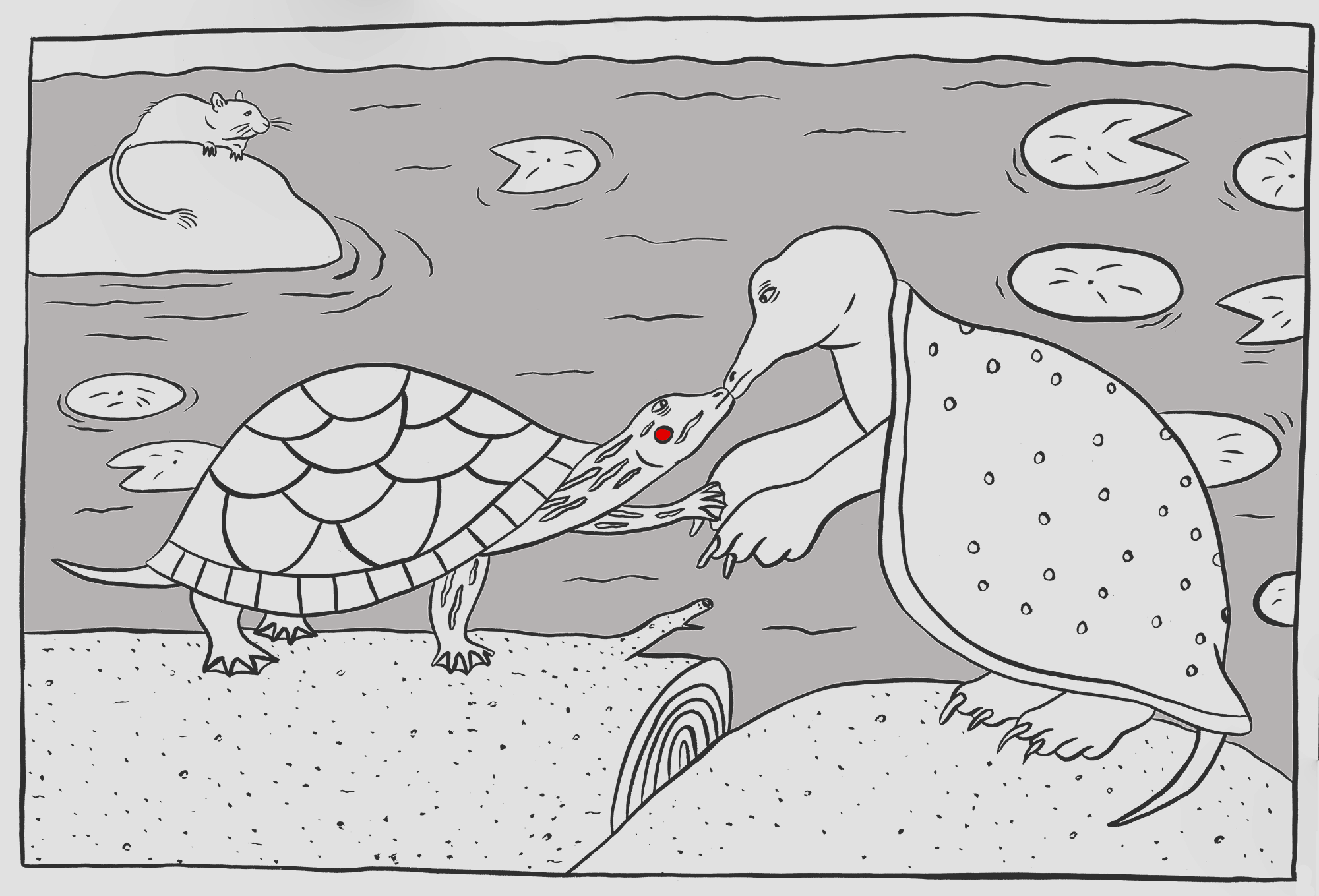

At thirty-seven, Maggie was three years older than me and beyond ready. I’d wanted to develop my career before motherhood—for the last few years I’d drawn a comic strip about lesbian turtles. Material success with comics seemed an impossibly distant goal, safe because it would take forever. No one bought the Sunday paper anymore and alt-weeklies were dead. And when would a comic strip about lesbian turtles ever hit the big time? Turtles are the least popular type of animal, and lesbians are the least popular type of human. But the strip launched briskly from a shabby online platform, with interest ballooning on social media. People fell in love with the painted turtle with her red dots by each ear and the bigger softshell turtle. People liked their warm, squinty eyes, I guess, their pointy overbites and the way they tried their best—flippers out, balanced on stubby flat feet—to press their plated chests together. The strip got syndicated in the surviving indie magazines and mainstream newspapers in cities like Portland and Portland. The pilot for a TV show had been funded and shot by a new, hip studio, which was considering buying a season. If the studio adopted the show, the turtles would appear on the small screen as black-and-white, stiff-moving cutouts, each character voiced by me, identically deadpan, and we’d move to LA. Whenever I remembered this possibility, I shuddered.

When the money for the pilot arrived, Maggie had asked to try. For years I’d given the excuse of my career—noble, logical, inarguable, and in the service, ultimately, of family. We needed money for a kid, of course, and Maggie didn’t deserve a co-parent who was harried and drawing in the shadows, sneaking away from milestones to ink in shell plates and beaky mouths.

Once my career turned toward the light, I had to face my issues that were harder to articulate. My father claimed I’d cried when he first held me, and he took this as a permanent rejection of physical affection. He’d been clear that I was a compromise, that he didn’t want kids. He demonstrated this, most days, by declining to participate. I was afraid my kid would feel the same—discarded, lonely. I’d never trust myself to be ready to welcome a little being to earth, though I was afraid to explain all this to Maggie, afraid she’d think I was loveless at my core. As months passed without my agreement, her frustrations accelerated.

Sometimes, when I was in a certain mood—a dangerous mood maybe, or cruel—I’d speculate on scenarios where the drudgery of domestic life provided me with a larger, more startling purpose, and I could almost justify making a child in my ambivalence. What if Maggie bore twins, one with my egg and one with hers? Our kids would bond so hard in the womb that it would be like me and Maggie combining in the popular, primal way. Maggie’s pinched-nosed kid stroking her lips like Maggie did, smoothing her T-shirt like Maggie did, laughing in a high keen like Maggie did, falling in sibling love with my kid with dark messy hair and skinny wrists. Did sperm banks provide an anonymous grab-bag option? We could spend years gathering data on the father through the behavior of our child—he must have short eyebrows, he must like cantaloupe with pepper, he must be mean.

We’d moved to Wyoming at the end of the summer to “think about it” in a neutral zone while we survived off the rent from our subletted apartment in New York. We nicknamed this period the Laramie Time. Maggie had abandoned her career in academic publishing to finish a novel. Our best friend, Arun, a chatty professor, had lured us out west, making the forgotten town with its slouching wood-frame houses and white men who stared at anyone who was not a white man seem cool. He assured us cougars crossed the highway and food was cheap. He secured us free housing from his colleague on sabbatical.

Maggie had been straight until me, and the idea of Laramie bothered her less. But when I fretted over the move, Arun insisted that the famous hate crime had unfairly stigmatized the town. He watched me closely while he explained that every resident knew that Matt Shepard and his killer had been lovers. The crime wasn’t homophobic or political but personal. As though that made it any easier to digest.

The colorful clouds and mountains, the antelopes and antelope-crushing brackets mounted to truck fenders, the beef, the clingy community of intellectual and creative semi-youths, they’d help the two of us decide one way or the other. And after three months of working side-by-side on the flower-patterned second-hand sofa, the tension of our future thickening the air and the results of Maggie’s fertility test landing on us like rotten whipped cream to top it all, I’d come around to the idea of creating a tiny third party to cheer us up.

When Arun, our sole visitor, was with us, Maggie and I had fun, setting bobcat skulls on our scalps and dancing, playing the same cute girls as always. Those days were the best: Maggie suggesting the three of us drive numbered country roads to Bamforth or Curt Gowdy or Hot Springs, or wander the foothills seeking buffalo while she spun stories about cows with warnings encoded in their spots or swingers sleepwalking over the prairie. Time, for me, dissolved when she got that way, all joy: the pharmacy, the dentist, stopped traffic behind a horse. But when we were alone, she scowled into the tiles, gruff and unpleasant. When she managed to leave the apartment at all, she wandered Safeway, buying cans of beans and desiccated nubs of ginger, gazing with reproductive lust at any man. She’d given up on her novel. She was unemployed in a borrowed apartment in the middle of Wyoming. A kid, I hoped, could bring her back.

That evening, Maggie and I ate buttered tangles of pasta around a mushroom-shaped ironwork table that was intended for outdoor use. Snow spattered the windows. It was only November and already it had snowed so often that we didn’t point it out anymore.

“So what should we name it?” I asked, to prove I was serious. Maggie had always taken care of me—financially and otherwise. I owed her this baby. I popped open my hands. “Let’s discuss.”

She laughed in her snorting way that made my heart lift. Her hand found mine under the table. She squeezed my fingers over and over. “Are we doing Theme Day? All these noodles.”

Back in New York, we used to sometimes focus all three meals on a color, or a texture, or some knobby vegetable pulled from the Chinatown market. I stroked her fingers so she’d relax her mechanical squeezing. Her hand seized up.

“I’m serious,” I said. “About the names. You must’ve thought of ideas.”

“You’re getting ahead of yourself,” she said. “It’s not even conceived.”

I shrugged. “But it’s fun to talk about, right?”

“Jane,” she said, anchoring her straw-colored hair behind her ear. “Or Michael. I’m sick of all those pretentious names.”

She returned to her pasta—the subject over, decided. What else would we talk about for however long it took to conceive plus nine months? Wasn’t jabbering about baby names, flapping through giant volumes, revisiting the hijinks of relatives long dead, how a couple worked up excitement over a forthcoming wrinkled intruder? What about Francine? What about Jiminy? What about Puck?

Maybe she’d reacted so glumly because of the lesbian turtles. Three weeks before, they’d agreed to adopt a gerbil with much more fanfare than I’d offered her. They’d cried. They’d crinkled their papery skin and performed their shell slapping embrace.

The next morning, I found Maggie pouring coffee to fuel her standard day of calling friends, useless shopping, walks that went nowhere, window sessions watching fake cowboys saunter by. She freelanced, but that only filled a few hours a week, which she stretched out by typing extra slowly.

“I better finish my work,” she said, a bite in her voice already. “Wouldn’t want to disappoint all the clamoring souls who rely on me.” She splashed coffee into her bowl until it spilled over.

Maggie admitted to thinking about her novel sometimes while she lazed around, though she maintained that she’d given up, that there was no point pouring your life into some document no one would ever read. What worried me was how she discussed the project of art: miserable, challenging, like she wanted me to quit my comic and mope around with her. I refused to get sucked into hopelessness. My grip on my work was shaky enough.

I snagged Maggie’s sleeve as she passed.

“Watch out.” She brushed my hand away to protect her coffee. She looked like a mole, like she always did at this hour, which was sweet. But today she looked worse than usual. The skin at the corners of her eyes was blue, and her cheeks were rough-textured the way they got when she was stressed. I’d hoped my agreement would make her happy. The turtles had hosted a garden party to celebrate their choice, frogs and tortoises emerging from under lily pads to fete the future moms.

Maggie jiggled her coffee bowl. “Can I sit, please? Am I allowed?”

“Here.” I pushed away my sketches. She scowled.

Most mornings I headed straight to my brush and dish of ink. Lately I had conference calls too, and sometimes I was in LA. I had treatments to rewrite and producers to please and animators to supervise. Half of what I did for the show—which the producers had dumbed down to Bisexual Turtles—I did in a trance. Whenever Maggie asked about moving to LA, wringing her hands and fretting about highways and smog and glad-handers talking shop, I told her not to worry. She was such a New York girl, striding through Manhattan in her black coat, snapping her way through editorial meetings while clinging to paper cups of coffee, acquiring her first-choice titles, always. Laramie was a way station, but LA was permanent, and the enemy.

I’d take my commitment one step further by discussing the sperm donor. The turtles only had to visit Gerbil-O-Rama—the shop that appeared on their shore the moment they needed it. We, on the other hand, had a process to slog through. Why not start? Maggie had abandoned her career and writing and left herself with nothing. Maybe she wanted a kid to distract herself from losing her novel. That was fair. I wanted that for her too.

I laced my fingers. “So,” I said. “The journey begins.”

She took a sip of coffee, squinting through the steam. “Excuse me?”

“So,” I said. “The journey begins.”

She set her bowl down. “I heard you. I just don’t have any idea what you’re talking about.”

Had she forgotten what we’d decided? “Our journey to have a child.”

Brightness flamed over her face, then extinguished. “What did you want to discuss?”

“We decided to do it,” I reviewed. “We settled on names. What’s left?”

“To get pregnant and have a baby and raise it to adulthood.” She spared a smile for her own joke. “If something’s on your mind, just say it.” One eye checked me curiously.

“The sperm,” I said proudly.

“Jesus, Leigh.” She peered at me up and down. “You’re really jumping in, aren’t you? You’re really on honor roll all of a sudden.”

“We have to select a man who embodies our values and love. We could have a fun ceremony where friends help choose from the sperm bank.” We’d be leagues more thorough than the turtles, who’d simply reached for the cutest gerbil in the box. We’d invite our Laramie acquaintances to debate dad options. I’d brandish placards with photographs of males and statistics. Did we want a San Francisco engineer who’s Boastful, Fun, and Curious? Or a math teacher who’s Creative, Wry, and Caring? Did we want a soccer buff who enjoys Potatoes, Chats, and Items? Or an oak tree fan with a Meaningful Childhood I Long to Replicate in a Baby Version of Myself?

“But Arun,” she said, studying me.

“What?”

“Who else?” The top of her face shone with anticipation, while her mouth remained downturned.

“Are you okay?” I inched my chair closer. I longed to embrace her, but she looked prickly.

“I’m fine.” She kissed me, sending a leak of molasses from my mouth to my core. If we weren’t discussing such urgent matters, if she wasn’t in a rotten mood, I’d have invited her upstairs to hide with me in the covers.

“Are you sure?”

“Certainly,” she said, in her professional voice, her hand sliding off my shoulder. “You’ve thought about it, haven’t you?”

But, of course, Arun was better than anyone narcissistic or desperate enough to peddle their bodily fluids. He was handsome and brilliant, an innovative critic whose mission was to write accessibly and increase public access to literary analysis. And he was our best friend. We’d known him since he was a graduate student in New York. We had endless fun in our group of three, while both of us were also close with him on our own. Still, I was disappointed not to debate. “He’s a start. But wouldn’t it be fun to throw around options?” I was desperate to discuss the decision, to comb through details, to convince myself this was real. Her vagueness, her rush to wrap up, was disturbing. “What about Rudyard?”

“Rudyard Beechpole? With the lank hair and aging rock star face?”

“He makes great chairs.” His chairs were carved from blackwood with curlicues whittled into the seats like wormholes. We’d wanted one until we’d seen the price.

“I don’t care if my baby makes chairs,” Maggie said.

“I wouldn’t mind new chairs.” I envisioned the apartment filling with increasingly elegant furniture as our baby developed as a craftsman.

Maggie snorted. “So Beechpole is a contender for you?”

“Not really.” I said, confused. Arun was the perfect donor. And I loved the names Michael and Jane. “I’ll call Arun now.”

Maggie looked up with a surprised frown. “Are you sure?”

I laid my hands flat on the table. “Maggie. Seriously. What’s up with you?”

“I was just asking.” Her coffee was nearly gone. She turned her bowl, swirling the dregs.

“I thought you wanted kids? I thought that was the central theme of our relationship?”

Her voice quieted. “But I want to know what you think.”

“I said I want to do this. I’m discussing the particulars.” I pressed down until my hands patterned with the table’s texture. “What more do you want?”

Maggie watched me, eyes pleading. I was terrified to question her further, afraid to unearth what was going through her mind. She got up and turned into the sink, rinsing her bowl for ages after it was clean. Had she only wanted babies so intensely due to my resistance? I watched her until she looked away.

For the rest of the day, I sketched Maggie in turtle form, finally appreciating my willingness to have a kid: kissing me with her beak, stroking me with her flat foot, dedicating to me the most intricate plate of her shell.

The weather turned the next week. Instead of dry slate skies confettied with snow, we were icy and windy and colder than ever. The hail gunfired down, cutting at the glass, and even the cowboys stayed inside. We ate canned corn with flaccid carrots on the days we couldn’t bear to trudge to the convenience store and treat ourselves to sad packets of gummy fish and crumbly Wyoming pork rinds.

Arun burst apart with happiness before I got the words out, gushing that he’d never wanted to raise his own kids, so he’d hoped we’d ask. On my own, I arranged and paid for his genetic and STI tests and hired a lawyer to draft a contract forfeiting his parental rights. We added a clause that we’d welcome informal involvement as all parties saw fit.

I wasn’t ready for the kid itself, but each step toward the kid was manageable. I consulted with the doctor over Arun’s perfect genetic score, initialing the contract, cutting checks from my turtle earnings. I was giving someone I loved what she wanted, though Maggie remained tepid, greenlighting each step without engaging. I acclimated to her coolness on the subject. Though it worried me in spikes, she’d waded through troughs of depression before. And maybe nothing was exciting when you’d wanted it too long. Maybe she’d burned out getting us to here. When the baby came, surely she’d revive.

I bought her the thermometer and predictor sticks and vitamins and a logbook, and though she showed no initiative, she used them at my urging, maintaining a record by the bed. She didn’t tell me when her body was ready. But I checked her journal, and when her LH hormone surged, I announced I was calling Arun.

I couldn’t wait to see him. Arun was sparkly. He would’ve been a star anywhere. He listened closely, as though what you said mattered, he was goofy the way men never are—subjugating himself for a laugh—and he was beautiful: his hair a soft ripple, his cheeks padded with the flesh of a teen. Once he was back in the apartment, the whole endeavor would make sense again.

Our first two months in Laramie, we saw Arun daily. He worked next to us on the couch after his classes and ate with us at the nineties-style vegetarian restaurant that leaned too heavily on bulgur. We hiked on the weekends without finding trails or paying for parks. We picked any mountain and pulled over on the country highway and marched through sagebrush and over deer ribs until we achieved the top, Maggie clinging to my arm, leaning her cheek against my shoulder and infusing me with love. She gathered treasures: a whistle, a lizard head, a thorn as thick as a fang. I saved them all.

One afternoon, at the summit of our favorite mountain, all of Laramie squatted before us. While Maggie exclaimed over the prairie, I pictured Matthew Shepard out there on a fence, slowly dying. Maggie asked what I was thinking and I said nothing; it was all so beautiful.

“I’m cold,” Arun said, and Maggie threw him her tank top as a joke, spinning off like a naked animal into the as pens. He pried the shirt over his head. The straps stretched across the drum of his chest, the cotton nearly tearing, and he called Maggie back, opening his arms. “Look—I’m finally a lesbian.” We laughed until we crashed down into the chaparral. That was the last afternoon Maggie and I were easy with each other.

The day after her positive surge, I met Arun at the door to our apartment building, by the block glass in the stairwell. His hand trembled as he brushed ice off his shoulder. “Am I early?”

“You’re perfect.” I sounded like I was hissing, “Let me steal your genes.”

“Cool,” Arun said. “I guess I should come in?”

I led him to the living room. Maggie was waiting upstairs. She was too nervous to socialize until the process was complete, but it felt wrong to send Arun off to masturbate instantly. Besides, I liked his company. Here was this thirty-five-year-old man, beautiful and brilliant with a perfect job, fine without a baby or even a girlfriend. He saw a few girls in town and sometimes took trips to LA, returning sunny and fortified. But largely he was the picture of someone who could be happy alone.

“How’s my Maggie?” he asked.

“She’s great.” Arun loved Maggie best. Everyone did. She was pretty, like a fairytale girl lost in the woods, but brilliant. Everyone said she should go for a PhD before she got too old. “She’s waiting upstairs.”

“I forgot what she looks like, it’s been so long.” He scratched the stiff chin of the taxidermied prairie dog we’d all bought on a joyride to Centennial. “If it weren’t for the paperwork, I wouldn’t have seen you either.”

“Things have been rough.”

He looked up, eyes big. “Oh, I know.”

“Can I get you a drink?”

“Nice seduction technique,” he said. “It’s 2:00 p.m.”

“How about pork rinds?”

“I’ll take a drink. By the way, this is the weirdest thing I’ve ever done.”

I’d been headed to the kitchen and I turned to laugh—Arun always put me at ease, how had I forgotten—but his face, forever photo-ready, had collapsed.

“You okay?”

“Just get me a drink.” His tone was steely.

In the kitchen, I fretted over what to serve. I’d stocked his favorites—beer, Jack and Coke, single-serving cans of a spritzer called Naughty Fruits—but none felt tonally appropriate. I pulled down a bottle of tangerine Schnapps, left over from a Christmas pudding, some bitters, and a novelty soda called Cool Mint Surprise. I whipped these with egg whites, grape jelly, and coconut shavings. The colors refused to integrate, though, and the drink was a bubbling, breathing rainbow.

Arun took one confused peek at my creation, helped himself to a swig, and grimaced. I wanted to tell him the drink was supposed to be funny. When he swallowed, liquid bulged down his throat. His face squished like he might throw up.

“Listen,” I said. “You don’t have to do this.”

Arun gulped more rainbow. Egg white foamed on his chin. “You know I want to.” He threw back another sip and the green layer of the drink splashed his shirt. He didn’t seem to notice.

“Are you worried you won’t get off or something?”

He nodded slowly. “I don’t masturbate that often.”

I held my face steady. “You don’t?”

“I’m sure I’ll squeeze one out.”

“Great.” In my comic, Arun was a lanky, long-legged tortoise named AJ who stopped by with sour-cream-and-onion snails and reptile puns. As a Shakespeare scholar, Arun found my comic unforgivably bizarre, though he treasured the small fame it afforded him with queer hipsters on campus. He’d been the most popular character since the beginning, according to the Twitterverse. If AJ isn’t on the show, I’ll slit my wrist with a box cutter, a tween had typed.

“You guys are good?” he asked, shifting his focus to the ceiling.

“Of course.” Since we’d moved to Laramie, I’d never seen Arun alone. “What do you mean?”

He shrugged at the ink on my wrist. I hadn’t slept, so I’d drawn all night. “Your career.”

This startled me. The issue with Maggie had always been kids. Everything else was perfect—the sex, the conversation; we both loved hiking and rice and audiobooks and begging bakeries for fresh bread at 4:00 a.m. Neither of us cleaned refrigerators or harped on dusting. The lesbian turtles had the same sole problem. In one strip, they gazed into each other’s beady eyes and whispered that they wished baby tur tles didn’t exist, that eggs couldn’t gel in their ovaries, or that reproduction was automatic or mandatory, so no decision was necessary. “There’s just that one issue between Maggie and me,” I’d told friends. “That one hitch.”

Arun relaxed against the cushions. “I mean, think about it. Your comic goes viral, it’s bought by some hip feminist studio, you might get a bigshot writing gig in LA?”

“She’s supportive.”

“No kidding.” Arun leaned forward, elbows on knees. “But think about it, Leigh. What’s Maggie doing?”

“Right now? Waiting.” I dropped stiffly into a chair. With no one to confide in, I hadn’t faced a hard truth in months.

“No, honey. She quit her job. She’s editing, like, ten pages a week for some startup.”

“But that’s her choice.” That last night of Maggie’s novel, she’d typed feverishly since predawn. She’d requested a stay on dinner, then another. As bedtime approached and we still hadn’t eaten, she shoved her laptop off the couch. “It’s all made up.” Her fingers fluttered on the air. “Completely fake.” Panic flickered in her eyes, but her body sagged in relief. Maggie’s novel was a drug. She’d worked on it constantly, miserably. She was a great writer—this was obvious even from her goofy road trip yarns—but writing made her miserable.

Arun watched me. “Do you really believe she’d give up?”

“It was sad, yeah, but she said she wanted it.” Guilt tugged at me. I suppose I should’ve tried to change her mind. I’d been too relieved to have my girlfriend back.

“Meanwhile, teen girls are coming over your turtles on Snapchat. And she’s doing nothing. You really believe that?”

I should’ve worked through the abandonment of her novel, ascertained Maggie was all right. I should’ve offered to read her book, or at least assured her I believed in her. We hadn’t talked about ourselves in ages. The kid question had subsumed us. If we discussed her novel, or LA, we circled back to kids. But I understood, with Arun’s disapproving gaze settling over me, that I should’ve forced the issue.

“That’s why this is good.” I gestured at Arun, accidentally aiming at his groin. We both grimaced. “Really, though. I’ve done what I wanted to do. And now I can do this.” Instead of this I almost said what Maggie wants to do.

Arun shook his head. “I should shut up.” His face softened like it would at a child. “But she’s still working on her novel, Leigh. She has been all this time.”

My body tightened. “What do you mean.”

“It’s going well,” he whispered. “Really well. So you don’t have to worry.” He leaned back and nodded, as though waiting for me to leap from my chair and dance.

“Oh.” My mouth stayed frozen. Maggie had been lying? Sneaking off to write? When? While I was asleep? When she was pretending to freelance? When I was in LA? I saw her waking at four after I left for a business trip, indulging in fifteen hours of writing, twenty, forsaking meals and snacks and the bathroom, her eyes burning dry, thrilled and alive. I’d understand if the work was going badly, if she wanted to turn the corner before she shared the news. But Maggie couldn’t write around me, couldn’t celebrate. Because of the turtles, or something else. “I knew that.”

Arun raised his eyebrows. “Did you?”

“Of course she told me. And I would’ve noticed anyway. You think she could hide that?” The words sent a crack of pain down my neck. We’d drifted so far apart. I’d failed to recognize creative euphoria in my own partner, living beside me in the middle of nowhere for three months. What was wrong with me? I cleared my throat, trying to sound natural: “Can I ask you something?”

Arun nodded, watching with concern.

“Why don’t you want to raise kids?”

Egg white shone opalescent on his chin. “You want to know?”

“Of course.” Nothing he’d say would change my mind. I’d heard all the arguments. I’d made them myself—global health, overpopulation, climate change, career surrender, drudgery. I hated chores. I hated shopping. I only liked one in a hundred kids—those were tricky odds. I didn’t want kiddie barfing diseases. I didn’t care about advancing my genes. I didn’t want Maggie’s body to change. I didn’t want to read a book about parenting. But everyone said once the kid was born, you were happy.

“No one would admit they made a mistake,” he said. “By having a kid, I mean. There’s too much investment.”

“Yeah, yeah.” I’d thought of that.

“That’s not why I’m scared, though.”

I should’ve ended the conversation—Maggie was waiting—but I had to ask. “Then why?”

“My nephew,” he said, “lives in Queens. When he was four he escaped his bed. He opened the front door and stood outside until a bus stopped. He got on the bus and rode into Manhattan.”

“No.” Arun exaggerated all the time for laughs.

“He did.” Arun set his empty glass on our steamer trunk. “My brother and his wife were asleep. They think the bus driver was high, but I bet everyone thought Sunil was with someone else. He rode over the Queensboro Bridge and into Midtown. He got off at Lincoln Center. Seriously.” Arun wore that hurt look he got when he feared we didn’t believe him. “Later people said they wondered about the kid. But no one did anything.” He rolled his eyes. “New Yorkers, man. No offense.”

Arun had forsaken New York to live as a pure Westerner. “Hey,” I said. “I’m in Wyoming now.” If I’d found that kid I would’ve scooped him up and ferried him to safety. I would’ve made him laugh in my arms until his parents claimed him.

“Anyway,” Arun said. “This lady found him.”

“Phew,” I said.

“No.” His face darkened. “It’s not good.”

Arun never talked about his family. His parents were nasty to him and, I suspected, abusive. Part of his love for Laramie was that there were only two planes a day into town. You saw one dangling in the sky and knew your visitor was on board. No one could sneak up on you out here.

“They went to a play.” Arun frowned. “I guess it had some weird stuff. A man dressed as a wolf, some naked kid, a stone people handled. It was a festival entry—the script isn’t published. I’ve checked. I’m sure you would’ve loved it.”

“So they saw a play,” I said. “So?” I liked the idea of a kid at a play: head bobbing at knee level, following me to museums and parks and afternoon pubs. Having a kid didn’t mean we were doomed to languish in pits of plastic balls.

“And we could figure out what he saw, right? We could find the script, interview audience members. But what gets me is the time around the play. Like what kind of person— and not to be sexist, but what kind of woman—sees a four-year-old lost in Midtown Manhattan and doesn’t call the police? Instead she takes him to a goddamn play.”

I looked at the ceiling. Maggie must be angry we were taking so long. Stress impaired conception. I pictured the wrinkles around her mouth deepening. I was afraid to face her, afraid of the girl who’d lied about her brilliant novel.

“Something bad happened. Sunil wasn’t the same after. He turned into this mini-adult. He didn’t bounce around like he used to. You don’t understand—he was a puppy before. These questions and silly voices all the time—even in timeouts he’d dance in his corner—and then, nothing. And it wasn’t just the play. He didn’t understand the play.”

“You think she molested him?” My heart skipped. I hadn’t met Sunil, but I pictured him anxiously eager, little hands grabbing the air, clowning as he bounced from foot to foot. “We’ll never know.” A moody expression bled over Arun. “Because he doesn’t know, but it affected him. He can’t tell us. Did she touch him? Did she say something? Did she show him a picture?” He gripped his knee. “Whenever I think of having kids, I fall into that panic. I know it would never happen again, but a thousand situations like it would. Little moments, sure, but I can’t stand the idea of letting the kid loose to live a private life.” He shook his head. “That spooks me.”

“I get it,” I said.

“I shouldn’t say this crap to you.” He raised his tumbler. “Your rainbow juice made me do it.”

I lifted my water, and we clicked glasses.

“But it’s okay—you’re not paranoid,” he said. “You haven’t had my family.” He didn’t know about my father, how I’d been unwanted. My story was pathetic in the face of the darkness he’d just shared.

“You’ll be a beautiful mother,” he said, regret wet in his eyes, whether for his own childhood or his missed fatherhood, I couldn’t tell.

I had a flash of wishing I’d been Arun’s mother. No, Sunil’s. I saw a hairy, upright beast lurching across the stage, a boy too shy to seize the sleeve of his chaperone. When it came down to assuming responsibility for a floppy body, loose in the world, I was sure I could be flexible and resilient, that I could put a little person first. Not only that I could do it but that I wanted to, and not only that I wanted to but that I had to.

I sent Arun upstairs with my laptop and a glass vial. I should’ve checked on Maggie, but the news about her novel, and Arun’s story, had me jittery. I lingered between my office, where Arun produced the ingredient, and our bedroom, where Maggie lay. Both rooms radiated tense silence.

I could picture my child, finally: small and dark-haired, strolling with me at the foot of the mountains. She was real to me now, so real I was afraid to touch the air at my hip for fear of grazing her head. But when I pictured life with her, Maggie wasn’t with us. I saw myself and the child, or the child alone, or another figure between us. Arun, even, but not Maggie. I’d told myself our relationship was perfect, and I hadn’t worried enough when the freeze set in. But she was writing away in secret, while pretending to be depressed—or she really was depressed. Maybe the novel was going well and she was sad she couldn’t share that—because of my success, or because of competition between us, or maybe the novel was about us and she didn’t want me to know. Whatever the reason, we couldn’t survive like this.

Losing both her and that dark-haired kid was a double punch in the gut. I loved Maggie. And I loved the kid already so much, ridiculously much, and she’d never even breathe. Now I understood what I’d lost: a girlfriend and a little person in a jasmine-flavored yard in Los Feliz, pulling vines off the house and training them up jacaranda trees, drawing with a sleeping baby’s sunlit face pointing up at me from a cozy sling. The hot red loops of nostrils, the mouth sealed with no reason to ever cry, the smell of sweet bread rising from that golden scalp.

I braced myself to tell her. But then I put it together. After I’d agreed to have kids, Maggie had never raised the issue once. She didn’t want a baby, or she’d come to the same conclusion I had and was afraid to tell me. So maybe we were on the same page. Maybe we could be okay.

The door to the office opened. One of Arun’s hands protected his crotch while the other extended the vial.

“Don’t look at it,” he said. “That’s too weird.”

“Thanks,” I said. “You can go.”

He looked at me, wounded. “Just like that?”

“I’m sorry.” I wanted this whole sad attempt over. “Please, Arun.”

“Okay, fine.” He’d hoped to be part of the family maybe, though he’d signed his rights away. “So long as you aren’t mad. About my story or whatever.”

Of course I was mad. “I’ll call you.”

I held the vial with two hands as Arun thumped down the stairs. The plan had been to keep the fluid warm and draw it with the syringe. I opened the bedroom door with a shaking hand.

Maggie was stretched naked on the bedspread. Her tawny hair covered her shoulders and the tops of her breasts. She smelled like sun-soaked hay: dry and hot and safe. This person had lied to me. She was happier than she could admit; she was thriving. My heart lifted for her joy, even if it was separate from me.

“Hi,” she whispered.

Warmth filled me despite the underheated room. I hadn’t encountered Maggie like this—lips melting, skin relaxed and smooth, breasts flushed pink—in weeks. I’d forgotten her body ready for me. “You okay?” I whispered.

“Can’t you tell?”

She lifted her arms and I dropped into them, the vial still clutched in my fist, heating it with all my might. Maggie’s velvet skin was exactly right, her skinny limbs curving around me, the ache of her breath on my forehead. “What changed?” I asked.

She pulled her head back. She was glowing. “I had to know you’re serious.”

The vial cooled between my fingers. How had this sludge been so recently inside a body? She wanted a baby.

“You were testing me?” I flashed with fuzzy, distant rage.

She tipped her head back. “Don’t talk. Just touch me.”

I was so grateful to be back with her that, even as a barb of anxiety drew through me, I hung above her, our bellies grazing. I saw Sunil in the dark as a man-wolf stalked the stage, seeking someone familiar. The turtles’ gerbil, so sweet and easy that he could never exist. He might be the only baby I’d ever create. But I couldn’t do it with Maggie. Not the silence and manipulation and lies. Not with a kid.

Tomorrow I’d tell her what I was about to do. We’d fight, in a subdued, broken way, and we’d be over. The enormity of what I’d done wouldn’t hit her for days, when she’d call me, furious. I’d leave her without a job or a girlfriend or a kid. I already knew how our end would play out, and I’d be right.

I drew the semen into the syringe. But before I pushed it into Maggie I aimed the tip down and pressed the plunger, freeing the sperm under the bed. Our baby, soaking into the carpet, my only chance, as it would turn out, and hers too. A shudder shook through me. I dipped the syringe into her and then I lay on her body, focusing on her dusty mammal smell.