WASHINGTON — NASA’s InSight Mars lander mission will likely conclude by the end of the year as power levels for the spacecraft continue to decline, project officials confirmed May 17.

At a briefing about the mission, which has been on the surface of Mars since November 2018, project leaders said science operations will likely end in July as the output of the spacecraft’s two solar panels, coated with dust, drops below critical levels. Increasing dust levels in the atmosphere from seasonal changes are exacerbating the power decline.

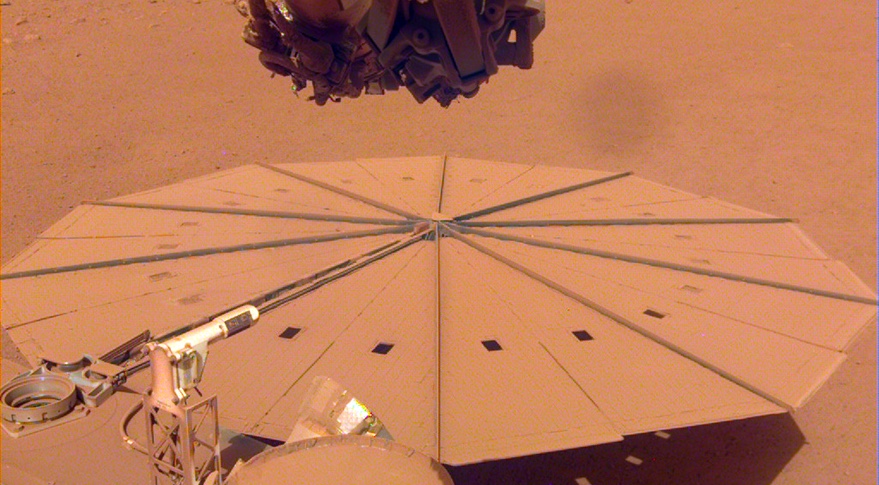

In the next few weeks, controllers will start shutting down some science instruments while putting the lander’s robotic arm into a “retirement pose,” with the camera on it oriented to see the lander’s primary instrument, a seismometer. That seismometer, which has been running continuously for most of the mission, will shift into intermittent operations this summer to conserve power before shutting down completely later this summer.

The shutdown of the seismometer, which would end science operations of the lander, could be as soon as early to mid-July, said Kathya Zamora Garcia, InSight deputy project manager. The project expects to maintain intermittent contact, including an occasional image from the camera, until late this year when power levels drop below what’s needed to operate altogether.

There is some uncertainty in that schedule, including hope that the lander could operate longer. “We’re in an operating regime we’ve never been in before,” said Bruce Banerdt, principal investigator for InSight at JPL. “As the power goes down, we’re not actually sure exactly how well the spacecraft will perform. It’s exceeded our expectations at just about every turn on Mars. It may last longer than that.”

The project has been warning for some time that, as dust continued to accumulate on the lander’s solar panels, power levels would drop and put the mission in jeopardy. Banerdt said at an advisory committee meeting in February that power levels would drop below what’s needed to operate science instruments in May or June, and below “survivability” for the lander itself by the end of the year.

Banerdt and others had hoped for a “cleaning event” to remove dust from the panels, such as a dust devil or wind gust. The panels generated 5,000 watt-hours of energy per Martian day at landing, but now produce just a tenth of that. Even a modest cleaning event could increase power levels enough to keep the mission operating.

Engineers tried other means to clean the solar arrays, using the robotic arm to scoop up regolith and drop it near the arrays, allowing the wind to pick up grains and bounce them off the arrays, jarring loose accumulated dust in the process. That created temporary boosts in power, which Garcia said provided another four to six weeks of operations of the lander’s instruments.

Banerdt said, in retrospect, he wishes the lander had some sort of mechanism for cleaning dust from the arrays, but that was one of the trade-offs for the mission to fit within the cost cap of the Discovery program. “If we put more money into the solar arrays, we would have less to put into the science instruments, so we tried to find the right balance,” he said.

Despite its impending demise, NASA called InSight a success, operating well beyond its primary mission of one Martian year. That assessment comes even though one of its major instruments, a heat flow probe, was unable to burrow into the surface as planned because of soil conditions not anticipated by instrument designers based on what had been seen at other landing sites on the planet.

That success includes the strongest “Marsquake” measured to date by the lander May 4, estimated to be a magnitude 5. Banerdt said scientists are still analyzing the data to try and pinpoint the source of the quake, which appears to be outside a known fault zone.

“There really hasn’t been too much doom and gloom on the team. We’re still focused on operating the spacecraft,” he added. “We’re still figuring out how to get the most science out of it.”

The project hasn’t ruled out trying to restore contact with InSight next year should a cleaning event remove dust from the arrays. NASA’s recent senior review of planetary missions found that there may be a slim possibility of doing so in mid-2023 after the winter season at the landing site.

“The Martian environment is very uncertain. We don’t know what’s going to happen,” Garcia said, with planned communications sessions just in case. “We’ll be listening.”