WASHINGTON — NASA is moving ahead with work on a pair of Mars sample return missions, although some in the planetary science community worry how the cost of that effort will affect other projects.

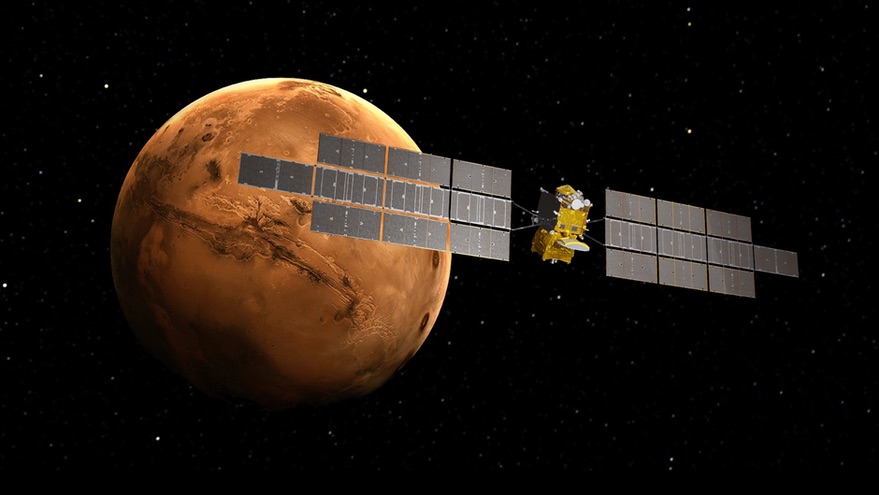

NASA announced Dec. 17 that it approved moving the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program into Phase A of development, working on initial designs of the missions and key technologies. Those missions include a sample return lander, whose development will be led by NASA with a rover provided by the European Space Agency, and an ESA-led orbiter with a sample collection system provided by NASA.

Under current plans, both the lander and orbiter would launch in 2026. The lander would touch down near the landing site of the Mars 2020 mission, with the fetch rover collecting samples cached by that mission. The Mars 2020 rover, Perseverance, may also deliver samples to the lander. Those samples would be placed in a container on a small rocket on the lander, launching them into orbit around Mars. The orbiter would then collect the sample container and return it to Earth in 2031.

The decision to proceed into Phase A of MSR comes after the release Nov. 10 of a report by an independent review board (IRB) that assessed the status and feasibility of the proposed missions. That review broadly endorsed continuing with the MSR program.

“We unanimously believe that the Mars Sample Return program should proceed,” David Thompson, former chief executive of Orbital ATK and chair of the board, said in media teleconference about the report. “We think its scientific value would be extraordinarily high.”

NASA, in its Dec. 17 announcement, said a separate standing review board for MSR also endorsed moving into Phase A. “Beginning the formulation work of Phase A is a momentous step for our team, albeit one of several to come,” said Bobby Braun, MSR program manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, in the statement. “These reviews strengthened our plan forward and this milestone signals creation of a tangible approach for MSR built upon the extraordinary capabilities of the NASA centers, our ESA partners, and industry.”

However, the independent review also raised questions about the cost and schedule for MSR. It recommended delaying the launch of the lander to 2028 and the orbiter to either 2027 or 2028. Thompson said the schedules for the two missions “were judged by the IRB to not be compatible with recent NASA experience.”

That review also concluded those missions will cost more than NASA projected. While NASA estimates a cost to the agency of $2.9–3.3 billion for those phases of MSR, the IRB concluded that a more realistic cost estimate was $3.8–4.4 billion. Those estimates do not include Mars 2020, which will cost NASA $2.7 billion through its first Martian year of operations, and ESA’s expected contribution of 1.5 billion euros ($1.85 billion.)

The cost of MSR is a concern for some planetary scientists, who worry about the effect it will have on the rest of NASA’s planetary science portfolio. That includes the ability for NASA to start any large-scale missions recommended by the ongoing planetary science decadal survey, which will present its final report in early 2022.

“This is a very important topic,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s planetary science division, during a town hall meeting Dec. 14 that was part of the Fall Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), in response to a question from an attendee on the effect of MSR on the overall planetary program. “I certainly do recognize and understand that it’s critically important that we maintain the balance within the portfolio and that we continue to have funding to support the other missions throughout the solar system.”

“We’ll rely on that decadal survey very heavily to determine what those priorities are and to help us provide that programmatic balance across all the various types of flight missions,” she added.

The ongoing decadal survey, though, won’t prioritize MSR against other proposed flagship-class planetary science missions. The previous decadal survey, published in 2011, ranked as its highest priority flagship mission a Mars rover to cache samples, which became Mars 2020.

David Smith, study director for the planetary science decadal survey at the National Academies, said during a Dec. 4 town hall about the study at the AGU Fall Meeting that “special language” in the terms of the survey meant that MSR would not be re-prioritized in the new study. “But, we are encouraged to comment on NASA’s current plans to implement the second and third phases of a Mars sample return campaign.”

That approach, he said, is similar to how decadal surveys in other science disciplines, like astrophysics, have dealt with flagship missions that ranked highly in one study but had not yet flown by the time the next study was underway. “The sponsor, NASA, does not want us to, in a sense, upset the apple cart but to give some sort of commentary on whether they are heading in the right direction.”

In the case of MSR, Smith said the decadal survey has requested budget information about the program, as well as a presentation on the IRB report. That presentation took place at a Dec. 16 meeting of the survey’s steering committee.