For many years, better opportunities on foreign shores, political turmoil, and the Maoist insurgency in Nepal have contributed to a large-scale migration to foreign countries. Many Nepalese writers, now settled in the West, have begun writing anglophone fiction and nonfiction about Nepal and its sociocultural history. Manjushree Thapa, Rabi Thapa, Chandra Gurung, and Samrat Upadhyay are some of the notable authors writing now. I engaged in a conversation with Upadhyay via email over the course of three months.

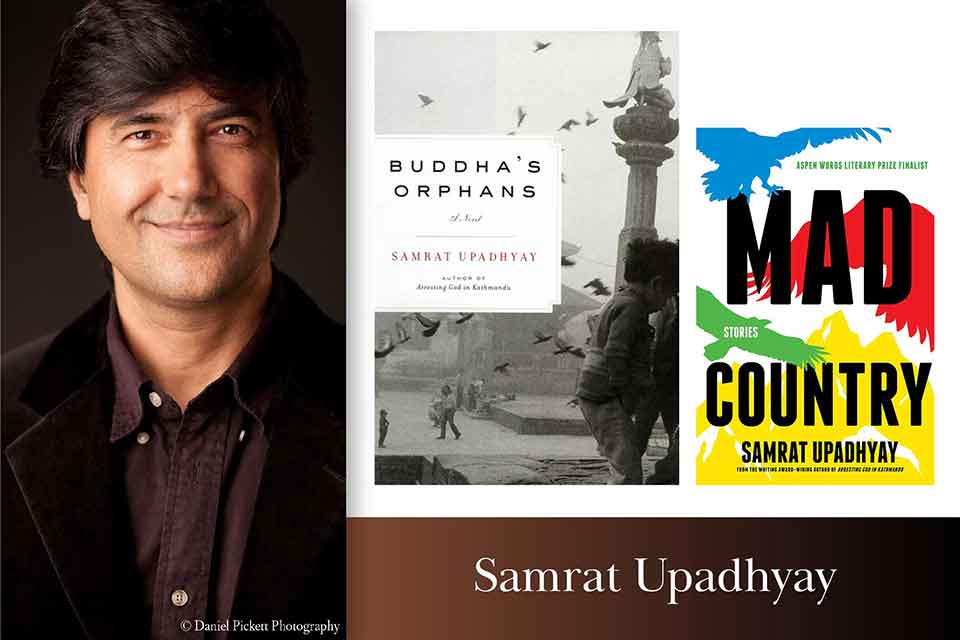

Born and raised in Nepal, Upadhyay is a Nepali diasporic author currently settled in the US. He is a Distinguished Professor of English and Martha C. Kraft Professor of Humanities at Indiana University, Bloomington. His works include Arresting God in Kathmandu (2001), The Guru of Love (2003), The Royal Ghosts (2006), Buddha’s Orphans (2010), The City Son: A Novel (2014), and Mad Country (2017). The first Nepalese writer to be published in the West, he won the Whiting Award for his debut book, Arresting God in Kathmandu, a collection of nine stories based on Nepal. His first full-length novel, The Guru of Love, was a New York Times Notable book of the year 2003. In 2007 he won the Asian American Literary Award for The Royal Ghosts. In the San Francisco Chronicle, Tamara Straus compared Upadhyay to a “Buddhist Chekhov.”

Koushik Goswami: What prompts you to write in English about Nepali life and culture? This is a neglected area in South Asian anglophone literature.

Samrat Upadhyay: Well, I am a Nepali who spent much of my early life in Nepal, so it’s natural for me to write about Nepal. I think part of the reason that Nepal is “neglected” is that the history of English-language literature in my country is fairly recent. Unlike India, for example, where the novel in English can be traced back to the mid-nineteenth century, Nepali English literature has proliferated only in the last few decades. As for my choice of English, I gravitated toward English during my teenage years and found that I had a certain facility with it. So, it made more sense for me to write in English than in any other language.

Goswami: You write from a diasporic space. Do you feel any conflict between homeland and hostland? How do you conceive the ideas of “homeland” and “hostland”?

Upadhyay: I think in the last couple of decades the lines have blurred between the concepts of homeland and hostland. Technology has also brought these two supposedly diametric spaces much closer. So, I feel increasingly less conflicted about these two ideas. I think that my recent fiction also reflects that to a certain extent: ideas and characters frequently travel from one space to another.

Goswami: Have you faced incidents of racial or any other kind of discrimination in the diasporic space? How will you define your identity abroad? Do you think that Nepalis are stereotyped and essentialized?

Upadhyay: Yes, I have felt racially discriminated, but more in my younger years as a student. I must say that given my position as a writer and a professor, I personally haven’t felt as discriminated against recently, but there is a great deal of systemic racism in the US, as recent events have demonstrated, especially under the Trump administration. As with any other groups, especially South Asians, Nepalis are stereotyped in the US. But they are also stereotyped in South Asian countries, where they are mostly seen as “bahadurs” who make excellent guards. It’s the writer’s job to break open these essentializations and provide new perspectives.

Goswami: What are the ground realities of the diasporic Nepalese, in terms of the cultural traits they retain and those they had to give up?

Upadhyay: Diasporic Nepalis is a large umbrella, and you get diverse types of people within this umbrella, so it’s hard to make generalizations. Many of the cultural identities have become fluid recently, especially with technology and access to materialistic comfort. Still, I find that food is a great unifier among Nepalis in diaspora. Food and certain cultural events unite many Nepalis in ways that are delightful and comforting and identity-affirming.

Goswami: What are the factors that lead to the migrations of Nepali citizens? Do they have to negotiate any specific identity issues abroad?

Upadhyay: Nepalis migrate for a variety of reasons. Many migrate to work (especially to the Gulf countries), and many migrate to Western countries for studies. Since the 1990s Nepalis have migrated to the US through the DV1 lottery. Some Nepalis struggle with identities because they don’t know how to find a comfortable balance between the cultural differences.

Goswami: You have spoken about the impact of riots and the Maoist insurgency on the people of Nepal. Do you think that the political uprisings have profound impacts on Nepali life as well as on Nepali literature and culture? Will you kindly elaborate on this in the context of your book The Royal Ghosts?

Upadhyay: There is no doubt that the Maoist insurgency changed the Nepali political landscape in major ways. It inflicted deep psychological damage that still has lingering effects. It led to mass migration from the hills to the capital. I tried to capture this in The Royal Ghosts, but it has also been a number of years now since the end of the Maoist civil war, so some of my literary interests have moved on.

But Mad Country is more a state of mind than anything else, and I think it points both to individual madness and to a collective madness of which we are capable.

Goswami: You have talked about different kinds of themes in your more recent book Mad Country—such as poverty, corruption, issues of identity, diasporic bondage, longing for diasporic lands—and also criticized political systems, democracy in Nepal, government and the establishment. Will you briefly justify the title and the theme of this book?

Upadhyay: The title actually doesn’t necessarily only refer to Nepal. At the moment that I wrote it, Trump had just become the president in the US, so I thought that it was also equally applicable to America. But Mad Country is more a state of mind than anything else, and I think it points both to individual madness and to a collective madness of which we are capable.

Goswami: In Arresting God in Kathmandu, you dealt with various truths of Nepali life. It addresses, on one hand, the traditional, religious, and cultural life of Nepal, and on the other hand, a longing for modernization. How would you describe the conflicts between traditional values and modern life in Nepal?

Upadhyay: I think in Nepal, as with many countries in Asia, there is always tension between the two. Many of the stories in Arresting God in Kathmandu were written in the late 1980s and early ’90s when these conflicts were more pronounced. Still, I think this conflict remains in Nepal, especially in more rural areas. Recently, in the mountains of Nepal, I saw a farmer’s daughter who tended to her goats in the mornings and took Zoom classes in the afternoons. In a way, this appeared “conflicting,” but perhaps much of it is in the eyes of the beholder because the young girl seemed perfectly comfortable in her two modes of living.

Recently, in the mountains of Nepal, I saw a farmer’s daughter who tended to her goats in the mornings and took Zoom classes in the afternoons.

Goswami: In The Guru of Love, Buddha’s Orphans, Arresting God in Kathmandu, and The City Son, you have narrated multilayered stories based on Nepal and beyond and received many prestigious awards for your contributions. How would you share your journey as a short-story writer and a novelist?

Upadhyay: I think I have been fortunate to be able to write in both genres and be published in both genres. I started out as a short-story writer but have been increasingly interested in the novel, its possibilities.

Goswami: How do you look upon Tibetan Freedom movements as a writer? Do you feel at one with the Tibetan writers in exile?

Upadhyay: I support Tibetans and their struggles under the Chinese occupation.

Goswami: How do you consider the Himalayas as a sociocultural space? Do you think there is common ground between the peoples of the different Himalayan nation-states? Or do you think that Himalayas act as a barrier? Do you think of the Himalayas as a geocultural region different from other South Asian nations? Can there be pan-Himalayan feelings and sympathy?

Upadhyay: I do think mountain people share certain attitudes and cultures and ways of living that can unite them. I have felt this affinity with peoples of the Indian Himalayas, for example, during my travels in India. Apart from this I don’t want to venture into other generalizations, as I believe that sometimes emphasizing differences tends to highlight the differences rather than pointing to our common humanity.

I believe that sometimes emphasizing differences tends to highlight the differences rather than pointing to our common humanity.

Goswami: What are your future plans in terms of creative writing?

Upadhyay: I am currently working on five novels, a trilogy and two short novels. The trilogy is dystopian, a dark comedy. One of the shorter novels is actually set mostly in the US and even has academia as its setting. My creative imagination has been a great source of nourishment and satisfaction for me in this stage of my career. I hope I’m able to continue writing until my death.

January 2021

Koushik Goswami is currently pursuing a PhD in the Department of Comparative Literature, Jadavpur University, Kolkata. He was a Humanities Visiting Scholar at the University of Exeter. Earlier, he completed his M.Phil in English from the University of Burdwan. He has published several articles in various journals, including “Rewriting Tibet in The Tibetan Suitcase: A Novel (2019) by Tsering Namgyal Khortsa” (Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities) and “The Tibetan Resistance Movement and Windhorse: In Conversation with Kaushik Barua” (World Literature Today). His areas of interest include South Asian literature, diaspora studies, and postcolonial literature.