Inspired by the way the skin on octopus arms works, researchers at Virginia Tech in the US have developed a new rapidly switchable adhesive that sticks securely to objects underwater. The material could find use in robotics, healthcare and in manufacturing for assembling and manipulating wet objects.

Adhesives that work underwater are difficult to make. This is because the hydrogen bonds and van der Waals and electrostatic forces that mediate adhesion in dry environments are much less effective in water. The animal world, however, contains lots of examples of strong adhesion in moist conditions: mussels secrete special adhesive proteins, creating a sticky plaque to attach to wet surfaces; frogs channel fluid through structured toe pads to activate capillary and hydrodynamic forces; and cephalopods like the octopus use suckers to adhere to surfaces via suction.

Strong adhesive bond

Cephalopod grippers are particularly good at holding things underwater. Octopi, for example, have eight long arms covered with suckers that can grab onto objects like prey. Shaped like the end of a plumber’s plunger, the suckers adhere to an object, quickly creating a strong adhesive bond that is difficult to break. “The adhesion can be quickly activated and released,” explains study team leader Michael Bartlett, “and the octopus controls over 2000 suckers across eight arms by processing information from diverse chemical and mechanical sensors.”

Indeed, an octopus’ sensing apparatus consists of a photoreception system that uses its eyes; mechanoreceptors that detect fluid flow, pressure, and contact; and chemoreception tactile sensors. Each sucker is independently controlled to activate or release adhesion – something that does not exist in synthetic adhesives.

The new Virginia Tech octopus-inspired adhesive consists of a silicone elastomer stalk capped with a stretchable pneumatically-actuated elastomer membrane to control adhesion. The stalk is made by 3D printing moulds and the silicone elastomer is then cast and cured. The adhesive element is connected to a pressure source that supplies positive, neutral, and negative pressure to control the shape of the active membrane.

“This design allows us to switch adhesion 450 times from the on to off state in less than 50 ms,” says Bartlett. “We tightly integrated these adhesive elements with an array of micro-LIDAR optical proximity sensors that sense how close an object is.”

The researchers then connected the suckers and LIDAR through a microcontroller for real-time object detection and adhesion control.

Glove with synthetic suckers and sensors

Underwater, an octopus winds its arms around objects and can attach to a variety of surfaces, including rocks, smooth shells and rough barnacles using its suckers. Bartlett and colleagues mimicked this by making a glove with synthetic suckers and sensors tightly integrated together. This device, dubbed Octa-glove, can detect differently-shaped objects underwater. This automatically triggers the adhesive so that the object can be manipulated.

“By merging soft, responsive adhesive materials with embedded electronics, we can grasp objects without having to squeeze,” said Bartlett. “It makes handling wet or underwater objects much easier and more natural. The electronics can activate and release adhesion quickly. Just move your hand toward an object, and the glove does the work to grasp. It can all be done without the user pressing a single button.”

These capabilities, which mimic the advanced manipulation, sensing and control of cephalopods, could find applications in the field of soft robotics for underwater gripping, applications in user-assisted technologies and healthcare, and in manufacturing for assembling and manipulating wet objects, he tells Physics World.

Several gripping modes

Octopus-inspired adhesive could heal wounds

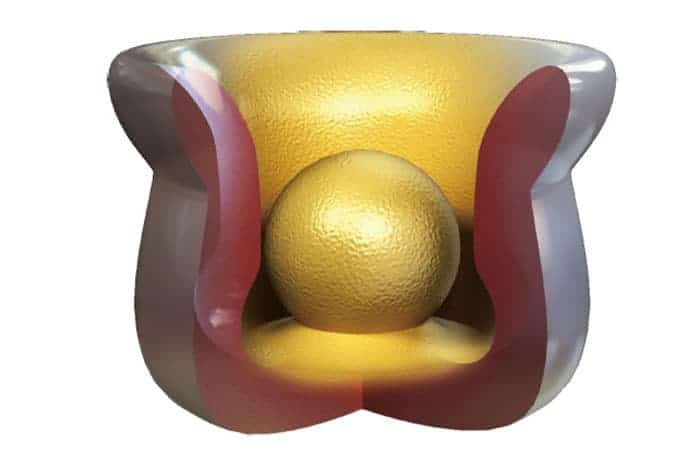

In their experiments, the researchers tested several gripping modes. They used a single sensor to manipulate delicate, lightweight objects and found that they could quickly pick up and release flat objects, metal toys, cylinders, a spoon and an ultrasoft hydrogel ball. By then reconfiguring the sensors to that multiple sensors were activated, they could grip larger objects such as plate, a box and a bowl.

The Virginia Tech team, reporting its work in Science Advances, says that there is still much to learn, both about how the octopus controls adhesion and manipulates underwater objects. “If we can better understand the natural system, this will allow to create more advanced bio-inspired, engineered systems,” says Bartlett.