Since Vladimir Putin launched his war of conquest and genocide against Ukraine on Feb. 24, there has been a sea change in the West’s dealings with Russia. Businesses and governments have abandoned partnerships and trade at the cost of billions of dollars. NATO countries have sent billions of dollars’ worth of military equipment and assistance to repel Russian invaders and help Ukraine survive a fight unsought and undeserved. Two historically neutral countries – Sweden and Finland – are now working to join NATO, bringing the alliance to long stretches of the Russian border.

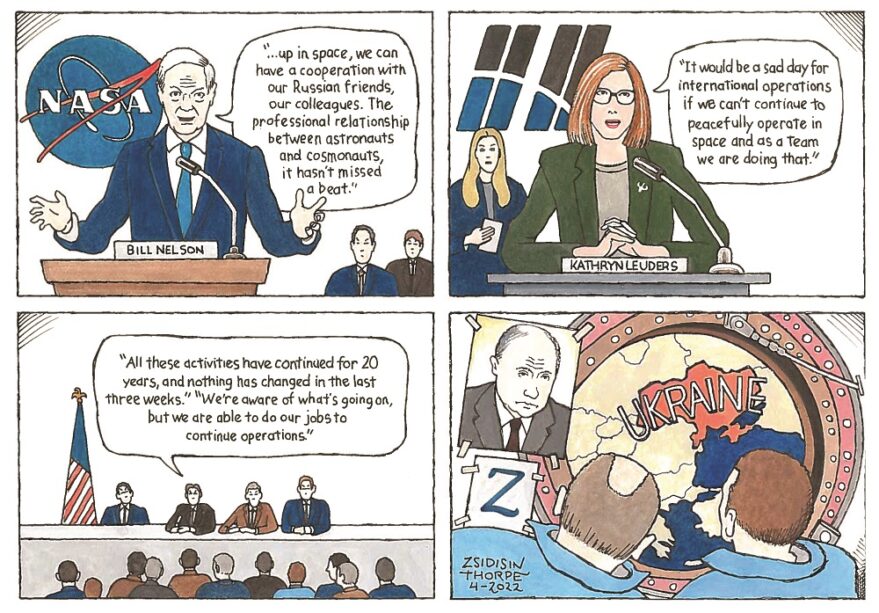

But at NASA, it has been business as usual. While the Western world and much of the global space industry severed ties with Russia over the war, NASA’s administrator and key managers for the International Space Station have continued to embrace the pariah state as a valued partner. Doing so lends Putin’s regime a highly undeserved place of respect and undermines all the other efforts to defend Ukraine and the West from Russia.

This has certainly not gone unnoticed. “NASA is on a very short list of entities still in public partnership with Russia — even Starbucks, McDonald’s and Coca-Cola have stopped doing business with the regime… We can’t ignore that Roscosmos is now part of Putin’s war machine,” noted Ann Kapusta, executive director of the Space Frontier Foundation, in March. “If they haven’t already, NASA needs to begin the process of severing ties.”

Former ISS commander and retired NASA astronaut Terry Virts recently made similar points. “The costs of our partnership with Russia on the ISS are now unfortunately much higher than the few remaining benefits,“ Virts wrote in a July opinion piece for The Hill. “I truly hope that we will someday return to cooperation in a post-Putin Russia, but for now, NASA and other partner nations must make the tough decision to begin the process of disengagement. The world is watching.”

Russia has since made that decision easier, telegraphing its intent to leave the ISS program after its current commitment ends in 2024 rather than stick around until the end of the decade as NASA and the other partners intend to do.

“We will definitely fulfill all our obligations to our partners, but the decision to withdraw from this station after 2024 has been made,” Yuri Borisov, the newly appointed head of Russia’s space agency, told Putin, according to July 26 state media reports that quickly made international news.

While Borisov’s successor, Dmitry Rogozin, had conditioned Russia’s participation in ISS beyond 2024 on lifting Western sanctions, NASA has sought to keep Roscosmos at the table while the 15-nation partnership formalizes an extension to 2030.

Whatever the intent behind Borisov’s cagily worded pledge to leave, the U.S. should accept the announcement at face value and direct NASA to prepare for Russia’s departure instead of trying to keep the marriage intact through 2030. Russia is not a partner in peace and will not be for years, if not decades, to come. NASA and its other partners should now formalize Russia’s departure date and outline the steps for achieving Russia’s overdue exit.

NASA leadership, however, appears unlikely to advocate such a course of action. In fact, in words and deeds, NASA appears to be heading in the opposite direction.

Doubling Down

On July 15, NASA doubled down on collaboration with Putin’s government with a new “seat swap” agreement on U.S. and Russian taxi spacecraft to the ISS. NASA bartered for more Soyuz seats despite the availability of U.S. commercial alternatives: the SpaceX Dragon that is already flying and Boeing’s Starliner that’s on the way. This dual-provider solution ensures access to the ISS and negates any claimed technical need for cross-capability on Russian taxi rides.

Russia’s involvement in the ISS, and NASA’s praise of its Roscosmos colleagues, are an insult to Ukraine and Western entities that have sacrificed so much in coming to its aid. The ISS’s public relations value was clear in early July when the three cosmonauts on the station celebrated Russia’s bloody landgrab in eastern Ukraine by raising the flags of two self-declared breakaway regions. In a social media post about the in-orbit flag ceremony, Roscosmos declared Russia’s capture of the Luhansk region as “a liberation day to celebrate both on Earth and in space.” Notably, one of the flag-waving cosmonauts, Oleg Artemyev, was the ISS commander at the time, a position that has by agreement changed hands between the U.S. and Russia since the start of the program.

Although NASA rebuked Roscosmos for using the ISS for political purposes, this likely won’t be the last such stunt Russia pulls. Putin recently rewarded Belarus for its help invading Ukraine with training for Belarus cosmonaut candidates, one of which Russia will fly to the ISS in 2023. Count on Russia turning the mission into another pro-war publicity coup.

Not Above Earthly Politics

In defending Russia’s continued participation in the ISS, NASA Administrator Bill Nelson has peddled the absurd notion that the ISS (and presumably NASA itself) rises above Earthly matters.

First: The ISS is the very definition of Earthly politics in action. NASA was moving forward with its own space station well before Russia was brought onto the program in the early 1990s following the Soviet Union’s collapse. A primary reason for this arrangement was to keep former Soviet scientists and engineers from providing their services to countries like Iran and North Korea. This “partnership” has propped up the Russian space program for decades. The U.S. has paid billions of dollars to Russia for its contributions, including Zarya, the first Russian ISS module, not to mention paying for seats on Soyuz taxis.

Second: The ISS is very much part of the Earth, spatially and politically. At the scale of a standard desktop globe of 30 centimeters, the ISS flies less than 10 millimeters over the surface. The ISS may be in freefall, completing an orbit every 90 minutes, but it is as much a part of the Earth as anything at sea or in the air. Indeed, the ISS flies so low that atmospheric drag would pull it out of orbit without periodic reboosts.

Even a glance at the Artemis Accords, NASA’s framework for international cooperation on the moon, shows that future space endeavors will be steeped in Earthly politics. This is demonstrated by Nelson’s hypocrisy of praising Russia while railing against China, a position made all the more inconsistent given that Russia is going over to the Chinese side for lunar exploration.

Amending the Wolf Amendment

Russia’s plan to depart from the ISS program ahead of the remaining partners presents thorny technical, logistical, and political issues since the ISS has been designed to have Russia joined at the hip. But NASA and Roscosmos must part ways and do so in a definitive, vocal, and public manner.

The political aspect should be easiest since ready solutions are at hand. For starters, the U.S. government should now formalize Russia’s departure as a given, and hearings should begin on how NASA will rework the ISS program with its remaining international partners.

Additionally, NASA must draw down its work with Roscosmos, particularly any interactions not related to the safety of the ISS and its crew.

There’s a straightforward method for NASA’s congressional overseers to force the issue, and it can still be done this year: modifying the Wolf Amendment, which severely restricts NASA from working with China, to cover Russia, with a proviso that all bilateral cooperation will cease once Russia’s ISS exit is achieved.

Congress enacted the Wolf Amendment in 2011, placing severe legal restrictions on NASA working with China. These restrictions have been regularly renewed as part of NASA’s annual appropriations process. As stated under Public Law 112–10, Sec. 1340:

(a) None of the funds made available by this division may be used for [NASA] or the [White House] Office of Science and Technology Policy to develop, design, plan, promulgate, implement, or execute a bilateral policy, program, order, or contract of any kind to participate, collaborate, or coordinate bilaterally in any way with China or any Chinese-owned company unless such activities are specifically authorized by a law enacted after the date of enactment of this division.

(b) The limitation in subsection (a) shall also apply to any funds used to effectuate the hosting of official Chinese visitors at facilities belonging to or utilized by [NASA].

Congress could amend this brief yet highly effective language to include Russia, worded to ensure that any permitted NASA-Roscosmos cooperation is limited to only what is essential to maintain the safety of ISS astronauts and Western ISS infrastructure.

While this may seem draconian, it would send a message that the U.S. is committed to further disengagement in light of the Putin regime’s continued barbarity. It also would force NASA to formalize the end of its experiment with Russia, which Congress has asked the State Department to label as a state sponsor of terrorism over its Ukrainian war crimes.

One important reason to update the Wolf Amendment stems from the U.S. intention to continue operating the ISS through 2030. The tenability of two or more years of partnering with Russia is already in question, while its antagonism towards the other ISS nations will likely worsen. It is time to discuss what the final days of Russian ISS participation will look like.

Winding down the ISS program in 2024 as codified by Congress a decade ago seems unlikely given White House and congressional support for extending the program to 2030. Indeed, Congress passed such an extension just before August recess as part of the bipartisan CHIPS and Science Act to bolster the U.S. semiconductor industry.

Regardless, ending ISS operations in 2024 — including “splashing” the entire aging complex into the South Pacific — remains a potential divorce option. While this would likely create a gap in human-tended experimentation in orbit, it could be at least partially filled by new crewed spacecraft coming online. Additionally, some of the $3 billion in NASA’s annual ISS operating expenses could go to advance commercial station concepts, enhance stop-gap measures, and potentially bolster funding for NASA’s Artemis lunar exploration program. That said, it must be recognized that negotiations with the other ISS partner nations on the future of ISS must inform any go-forward plan.

Should the overall ISS end date continue to be 2030, the hardest aspect of divorcing Putin could be logistics. What happens as the end of Russian participation approaches? July’s bellicose flag stunt gave us a taste of the character of today’s cosmonauts. Given the actions of Putin’s government against Ukraine, and its repeated nuclear threats against some of the very nations that make up the ISS program, serious malfeasance leading up to a Russian closeout has become much more imaginable. The safety of the ISS and its crew must be ensured during the divorce.

The technical issues involved in a split will depend on the approach that is negotiated. Replacing the reboost function that Russia currently provides is not trivial, but not insurmountable either. Near-term solutions include propulsion from Cygnus cargo spacecraft, the mothballed ISS Interim Control Module, and even efficient electric propulsion technology now under development for NASA’s lunar Gateway. Studies of the physical separation of Russia’s modules from the rest of the ISS are said to show this would be difficult but possible, should that be required in the end.

Embracing Russia’s Overdue Departure

It’s time for those who oversee NASA — in Congress, in the State Department, and even now in the White House — to tell the U.S. space agency that it too must play a role in disengaging from Putin’s regime. NASA is not exempt from the moral, financial and logistical obligations that the war on Ukraine – a war opposed by all the other nations in the ISS program – has created.

The U.S. government can force a “shotgun divorce” between NASA and Putin in several ways:

- Direct NASA to end any further crew seat barter discussions between Russia and the U.S., if not actually rescind those currently planned.

- Formally recognize Russia’s planned departure and direct NASA to drop Roscosmos from any plans for extending ISS to 2030.

- Update the Wolf Amendment to prevent NASA from working with Putin’s regime beyond supporting Russia’s swift but orderly departure from the ISS program.

The ISS is not above earthly politics, except perhaps in the narrowest physical sense. The partnership with Russia must be viewed anew under the dire circumstances Putin has created in Ukraine and his willingness to turn the ISS into a platform for pro-war propaganda.

Putin’s Russia deserves to be thrown off the ISS, one way or another. It’s time to welcome Russia’s promise to leave and ensure they do not disrupt the rest of the program on their way out of the airlock.

Greg Zsidisin is an engineer and writer in Huntsville, Alabama. In the 1990s, he served on the board of the National Space Society, was president of the NSS Chapter in New York City, and chaired that organization’s annual conference in 1996. The views expressed above are those of the author.

This article originally appeared in the August 2022 issue of SpaceNews magazine.