It’s fitting that two of the first three essays in this roundup are centered on examining the Black American experience as one of horror. In a year when radical right-wing activists are truly leaning in, we’ve already seen record numbers of anti-LGBTQ legislation, the very real possibility of the end of Roe v. Wade, and more fervent redlining measures to keep Black people (and other marginalized communities) from voting. Gun violence is at an all time high, in particular mass shootings.

Since the success of Jordan Peele’s runaway hit film Get Out, there has been a steady rise in films depicting the Black American experience for the fraught, nuanced, dangerous life that it can be. This narrative isn’t entirely new, but this is the first time these films have gained critical acclaim and commercial attention. The reason is simple. Whatever the cause—social media, an increasingly diverse population—America can’t run from itself anymore. Our entertainment is finally asking the question that Black people have been asking for generations: In America, who is the real boogeyman?

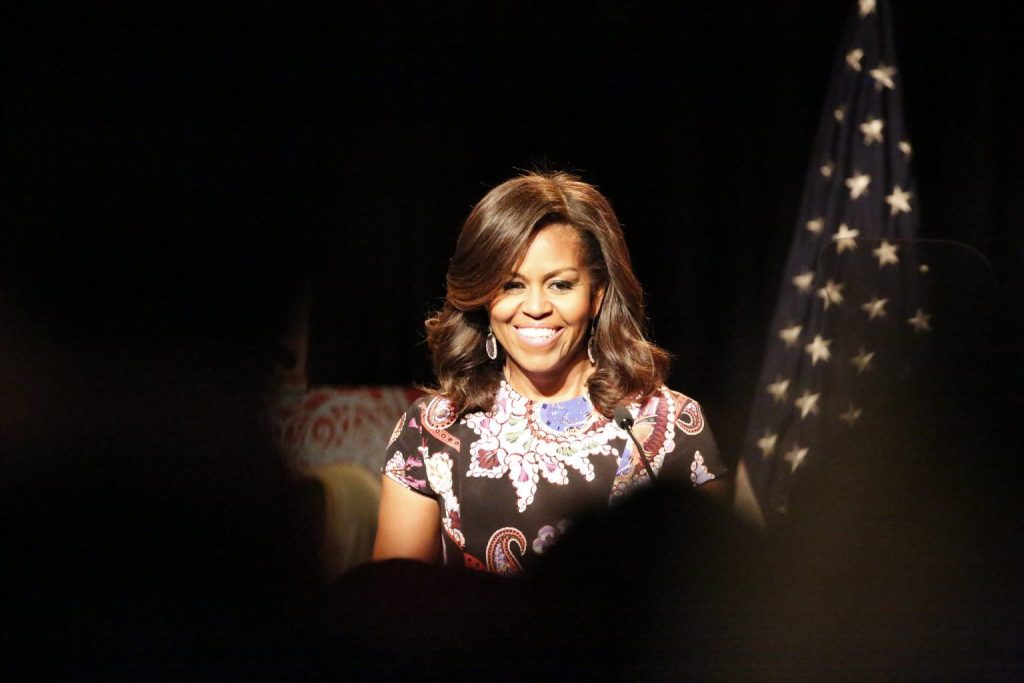

Naturally, the discourse and critical analyses must follow suit. But it doesn’t stop there: the essays on this list span far and wide when it comes to subject matter, critical lens, and personal narrative. There are essays about Black friendship, the radical nature of Black people taking rest, and the affirmation of Black women writing for themselves, telling their own stories. Icons like Michelle Obama, Toni Morrison, and Gayle Jones get a deep dive, and we learn that we should always have been listening to Octavia Butler. This Juneteenth, I hope you’re taking a moment to reflect, on America’s troubled legacy, and to celebrate the ways that Black people continue to thrive.

Modern Horror Is the Perfect Genre for Capturing the Black Experience

Cree Myles writes about the contemporary Black creators rewriting the horror genre and growing the canon:

“Racism is a horror and should be explored as such. White folks have made it clear that they don’t think that’s true. Someone else needs to tell the story.”

Modern Narratives of Black Love and Friendship Are Centering Iconic Trios

Darise Jeanbaptiste writes about how Insecure and Nobody’s Magic illustrate the intricacy of evolving Black relationships:

“The power of the triptych is that it offers three experiences in addition to the fourth, which emerges when all three are viewed or read together.”

I Was Surrounded by “Final Girls” in School, Knowing I’d Never Be One

Whitney Washington writes that the erasure of Black women in slasher films has larger implications about race in America:

“Long before the realities of American life, it was slasher movies that taught me how invisible, ignored, and ultimately expendable Black women are. There was no list of rules long enough to keep me safe from the insidiousness of white supremacy… More than anything, slasher movies showed me that my role was to always be a supporting character, risking my life to be the voice of reason ensuring that the white girl makes it to the finish line.”

“Palmares” Is An Example of What Grows When Black Women Choose Silence

Deesha Philyaw, author of The Secret Lives of Church Ladies, writes that Gayl Jones’ decades-long absence from public life illuminates the power of restorative quiet:

“These women’s silences should not be interpreted as a lack of understanding or awareness, but rather as an abundance of both, most especially the knowledge of what to keep close to the vest, and the implications for failing to do so. They know better than to explain themselves, their powers and their origins, their beliefs and reasons, their magic. These women are silent not because they don’t know anything. They are silent because they know better.”

Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye” Showed Me How Race and Gender Are Intertwined

For the 50th anniversary of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, Koritha Mitchell writes how the novel taught her that being a Black woman is more than just Blackness or womanhood:

“I didn’t have the gift of Kimberlé Crenshaw’s concept of ‘intersectionality,’ but The Bluest Eye revealed how, in my presence, racism and sexism would always collide to produce negative experiences that others could dodge. It was not simply being Black or being dark-skinned that mattered; it was being those things while also being female.”

The Delicate Balancing Act of Black Women’s Memoir

Koritha Mitchell writes about how Michelle Obama’s Becoming illustrates larger tensions for Black women writing about themselves:

“In other words, when Black women remain enigmas while seeming to share so much, they create proxies at a distance from their psychic and spiritual realities because they are so rarely safe in public. Despite the release of her memoir, audiences will never be privy to who Michelle Obama actually knows herself to be, and that is more than appropriate.”

50 Years Later, the Demands of “The Black Manifesto” Are Still Unmet

Carla Bell writes about James Forman’s famous 1969 address, The Black Manifesto, and its contemporary resonances:

“But the Manifesto is as vital a roadmap in our marches and protests today as the day it was first delivered. We, black people in America, remain compelled by the power and purpose of The Black Manifesto, and we continue to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.”

You Should Have Been Listening to Octavia Butler This Whole Time

Alicia A. Wallace writes that Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower isn’t just a prescient dystopia—it’s a monument to the wisdom of Black women and girls:

Through her protagonist Lauren Olamina, Butler has been telling the world for decades that it was not going to last in its capitalist, racist, sexist, homophobic form for much longer. She showed us the way injustice would cause the earth to burn, and the importance of community building for survival and revolution. Through Parable of the Sower, we had a better future in our hands, but we did not listen.

The Book You Need to Fully Understand How Racism Operates in America

Darryl Robertson writes about Ibram X. Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and its examination of the history of overt and covert bigotry:

“While How to Be an Antiracist is an informative and necessary read, it is his National Book Award-winning, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America that deserves extra attention. If we want to uproot the current racist system, it’s mandatory that we understand how racism was constructed. Stamped does just that.”

I Reject the Imaginary White Man Judging My Work

Tracey Michae’l Lewis-Giggetts turns to Black writers as inspiration for resisting white expectations:

“…it doesn’t only matter that I’m a Black woman telling my story. What matters is the lens through which I’m telling it. And sometimes, many times, that lens, if we’re not careful, can be tainted by the ever-present consciousness of Whiteness as the default.”

Toni Morrison Gave My Own Story Back to Me

The incomparable literary powerhouse showed Brandon Taylor how to stop letting white people dictate the shape of his narrative:

“That’s the magic of Toni Morrison. Once you read her, the world is never the same. It’s deeper, brighter, darker, more beautiful and terrible than you could ever imagine. Her work opens the world and ushers you out into it. She resurfaced the very texture and nature of my imagination and what I could conceive of as possible for writing and for art, for life.”

Art Must Engage With Black Vitality, Not Just Black Pain

Jennifer Baker writes that books like The Fire This Time give depth and nuance to a reflection of Blackness in America:

“These essays provided a deeper connection because Black pain was part of the story; Black identity, self-recognition, our own awareness brokered every page. Black pain was not the sole criterion for the anthology’s existence.”

When Black Characters Wear White Masks

Jennifer Baker writes that whiteface in literature isn’t a disavowal of Blackness, but a commentary on privilege:

“Whiteface stories interrogate the mentality that it’s better to be white while examining how societal gains as well as societal “norms” inflict this way of thinking on Black people. Being white isn’t better, but, for some of these characters, it seems a hell of a lot easier, or at least preferable to dealing with racism.”