President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on Jan. 1, 1863, ordering that “all persons held as slaves” should “be free.” But some enslavers across the Deep South refused to comply, and many Black people remained in slavery—completely unaware of their new freedom. Finally, on June 19, 1865, Union soldiers in Galveston, Texas, delivered an order, announcing that Black Texans were free, a moment that would come to symbolize the end to chattel slavery.

As of last year, that day, known as Juneteenth, has been designated a federal holiday. Juneteenth should be a formally recognized holiday; as a nation, we need to tell the truth about American history. But the day also deserves our solemn respect, because Juneteenth commemorates one of the most harrowing examples of what Black Americans have endured in this country—and how much we are owed. The first Juneteenth celebrations included voter registration rallies and collectively purchasing property. But since then, corporations have begun to profit off of what was previously a sacred, intra-community day. In the face of diluted messages and sacrilegious marketing, we need to reclaim Juneteenth from capitalism. How can we return to the radical tradition of building political power for Black communities? By centering the voices of Black women dedicating their lives to reckoning with our past and investing in repair.

This Juneteenth, ELLE.com brought together Dr. Keisha N. Blain, Jillian Hishaw, Kavon Ward, and Alicia Garza to shed light on reparations as a call to action. Dr. Blain is a best-selling author, incoming professor of Africana studies and history at Brown University, and an award-winning historian; Hishaw is an agricultural attorney who advocates for small farmers; Ward is the founder of Justice for Bruce’s Beach and the CEO and founder of Where Is My Land, an organization tracing stolen Black land and campaigning for its reclamation; and Garza is the principal at Black Futures Lab and a co-founder of the Black Lives Matter movement.

For too long, justice has been denied to Black Americans. Below, these four women discuss the need to look back at this nation’s foundation in order to move forward.

Dr. Blain, you’re a historian by trade, and you write books that challenge what we think we know about American history. What do people most get wrong when talking about reparations?

Keisha N. Blain: I wish more people knew that the struggle for reparations in the United States has a very long history. It’s also important to note that Black women were often at the forefront of this fight—another fact that tends to be overlooked in mainstream narratives about reparations in the United States. Here, I am thinking about courageous women like Belinda Sutton, a formerly enslaved Black woman in Massachusetts who petitioned the Massachusetts General Court in 1783 in an effort to receive a pension from the estate of her deceased former owner. At its core, the petition was a demand for reparations; Sutton explicitly referenced her years of labor. This longer history of reparations helps to counter the argument that present-day white Americans bear no responsibility for developments in the past. Black people have been demanding reparations for centuries—and the campaign has continued because they have been denied for centuries.

Jillian, your book Systematic Land Theft answers the question of why 97 percent of U.S. land is owned by white Americans. What have you learned throughout your legal career about the relationship between Black people and land?

Jillian Hishaw: As an attorney, I have learned that English common law serves as the foundation for our legal system to this day, and is used to push Black people off of our land. This makes sense when you consider that English common law was adopted during European settlement, and its foundation was structured to discriminate. I witnessed that not only as a legal expert, but also in my own genealogical history. My family [members] were enslaved, and unfortunately, the 40-acre farm that they received in reparations was stolen by a dishonest lawyer. This is one of the many reasons why I became a lawyer: to offer honest legal services and prevent further land loss.

Kavon, you co-founded Where Is My Land to reclaim stolen land. Is there a campaign you’re working on that exemplifies why you do what you do?

Kavon Ward: The Burgess Brothers immediately come to mind. The state of California took about 80-plus acres of land from Jon and Matt’s ancestor Rufus Burgess in 1949; many parcels of Rufus’s land were condemned and seized through eminent domain. Their land is now a part of Marshall Gold Discovery State Historic Park in Coloma. Despite having deeds to their family land dating back to 1872, they’ve had to fight with the California State Parks Department to ensure an accurate history of the land is told. We see this rewriting of history in real time to erase us.

Alicia, can you tell us more about Black Futures Lab’s work to right historic wrongs, and what you’ve noticed about people’s lack of political imagination, specifically when it comes to reparations for Black Americans?

Alicia Garza: At the Black Futures Lab, we work to make Black communities powerful in politics so that we can be powerful in all areas of our lives. We train our communities how to write new rules and get them passed, in order to replace the ones that are rigged. We tell new stories about who we are and who we can be together. Reparations aren’t just about getting a check—they’re about changing the rules to right historic wrongs and to keep those wrongs from happening again. How do we repair the lack of representation of our communities in positions of power? How do we reimagine how governance works so that Black folks aren’t on the listing end of where resources go and don’t go? How do we reimagine the economy?

What will it take to actually repair the trauma and theft initiated during chattel slavery, which continued throughout every step of this nation’s development?

Hishaw: I have been doing this work for over 20 years, and the history of oppression we have experienced as a community will outlive all of us.

Ward: Future harms will occur if we don’t admit and teach the truth about all American history, including harms inflicted upon Black people by white people such as enslavement, a failed Reconstruction era, Jim Crow, and present harms like mass incarceration and the murder of Black people by police and emboldened vigilantes. It will take so-called white allies stepping up, stepping aside, and relinquishing their power. Performative advocacy doesn’t work. It’s time to stop talking about it and start being about it.

What are the strategies toward repair that you all want to see in the world?

Blain: I’m not certain that the trauma of chattel slavery can be repaired. I don’t know if most of us are truly equipped—psychologically—to conceptualize or even process the trauma caused by treating people as commodities. So, I’ll leave the question about how to repair trauma to psychologists, but I think we can directly address the matter of theft. How do you repair theft? Well, one approach is to return what has been taken or, at the very least, one can offer redress for the value of what was taken.

Garza: There are at least three important strategies that could, and in some ways are, being deployed toward repair that I would like to see. The first is to build a deeper cultural understanding of why repair is important and, more than that, why it’s important for everyone, not just for Black people. Enslavement is not just a deep moral stain on this country’s history—it is embedded in our present, from the economy to our democracy. More people need to understand the tangible impacts of that. The second is to pass laws and allocate resources toward repair. Currently, we have a lot of task forces that are largely without decision-making ability; we need committees with teeth, and more bills navigating their way through legislative committees. And finally, for that to happen successfully, we need to organize more people to advocate for these laws. Unlikely coalitions could help build the kind of power we need to move legislation that changes the rules and allocates more resources towards this project.

What can individuals do to fight for reparations in their personal lives?

Hishaw: Reparations start with collective efforts. For example, I am currently working on a project where white landowners are giving land to future Black farmers so they can build farming communities. Everyone can also donate to organizations like F.A.R.M.S., where we have a successful track record of saving Black-owned farmland. I also want to speak specifically to Black people: In writing Systematic Land Theft, I learned we are natural cultivators of the land but, at the same time, have a contentious relationship with agriculture. Many Black people still affiliate farming and land ownership with slavery and want to be far removed from it. Many treat the soil like dirt and view the land as a tax burden. We must value land and natural resources.

What can members of the media do differently in framing and commenting on these conversations?

Garza: They can unearth more places where enslavement has created the wealth and conditions we experience today in order to help build a public consciousness around the need for reparations.

What role do companies and for-profit entities play in the advancement of reparations? What about elected officials and people in government?

Blain: Companies need to be held accountable for their past actions, as well as contemporary discriminatory practices. Consider Wells Fargo. According to a recent report, the bank only approved 47 percent of Black homeowners who applied to refinance their mortgage in 2020 compared to the 72 percent approval rate for white homeowners. Black customers have responded and are now suing the company. And there are many companies that directly profited from slavery, for example, New York Life Insurance. These companies can do more than release public statements and apologies. They can start by devising concrete strategies to redress harm, including fair and equitable policies, as well as programs that specifically administer funds into Black communities.

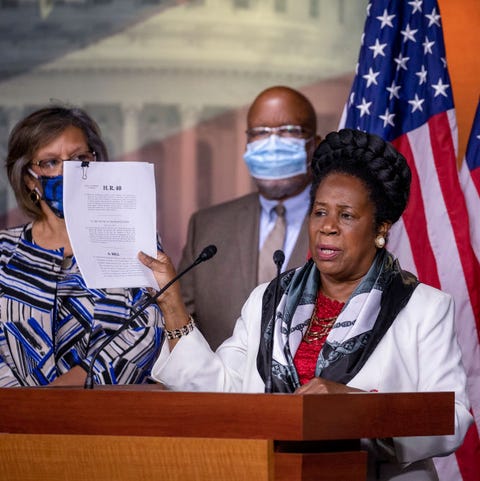

Right now, the major push for reparations [at the federal level] is H.R. 40: Commission to Study and Develop Reparations Proposals for African Americans Act. Since 1989, Black lawmakers—first John Conyers and now Sheila Jackson Lee—have introduced a version of this bill in the House of Representatives. In April 2021, for the first time in 30 years, the bill was voted out of committee. However, it has not been introduced to the floor of the House. I certainly hope we will see some momentum around this bill in the future, but this is a small step. I’m all for studying the issue, but we already have ample research available to come up with bold and creative solutions.

These interviews have been edited and condensed for clarity.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io