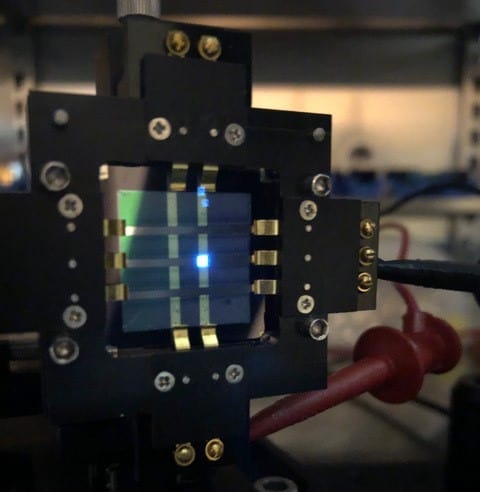

A photonic crystal emitter has been fabricated by stacking multiple organic light emitting diode (OLED) microcavities into a single structure. It was created by a team led by Matthew White at the University of Vermont in the US, who demonstrated that the degree of interaction between the cavities depends strongly on the different layers employed, meaning both the colour of light emission and the band structure of the devices are highly tuneable. This paves the way towards electrically-driven photonic crystals that allow further control over the emission of OLEDs. The full study is described in Nature Communications.

OLEDs have received a large amount of attention in recent years due to their numerous applications in display screen technologies and efficient low-cost lighting. They are also easy to integrate into other technologies and structures.

White and colleagues have placed semi-transparent mirrors on either side of an OLED to form a microcavity – that is, a cavity with a length on the order of a micron. By varying the distance between the two mirrors, the length of the cavity and therefore the emission wavelength (colour) of the OLED can be finely tuned, even without changing the organic material.

Communicating OLEDs

The team then created a stack of N microcavities separated by semi-transparent mirrors to make a device with a photonic band structure analogous to that in a photonic crystal. If the mirrors are much thicker than the penetration depth of light, no communication between the cavities is possible and they act as N separate cavities. Conversely, if the mirrors are infinitely thin, the N cavities will act as one cavity with a total length Nd, where d is the length of each individual cavity.

If the mirror thickness lies between these two extremes, the system acts similarly to that of the extended cavity, but with small perturbations in the electric field caused by the internal mirrors. This results in a hybridization of the energy states, forming a photonic band structure that is similar to a photonic crystal or hybridized orbitals in molecules. This hybridization alters the energy of the states and therefore affects the OLED emission.

The researchers have shown that the band structure is heavily dependent on the properties of the stack. For example, the internal mirrors used in the stack alternate between silver and aluminium. This symmetry breaking doubles the unit cell size so that it consists of two cavities with a semi-transparent internal mirror and total length equal to 2d.

Tuning the band

As aluminium has a shorter penetration depth and higher losses than silver, the aluminium mirrors primarily control the length of the unit cell and therefore the energy separation of the hybridized states. The researchers have shown, however, that the presence of the silver mirror perturbs the states, decreasing the energy gap between the two sub-bands. Therefore, by altering the thickness of the different mirrors, it is possible to control the size of the band gap, the separation of the energy states and the total bandwidth of the OLED stack.

Stacked molecules create efficient and stable pure-blue OLEDs

“The effect is the result of structural colours so we can use green organic emitters, which are known to be more stable, to produce any desired colour combination”, says White. In this way, it will be possible to “tune the emission from OLEDs to include broadband white light, narrow bandwidth single peaks, or multiple peaks forming a low-fidelity frequency comb”.