SAN FRANCISCO – After four years and six competitions, SpaceNet, the nonprofit focused on geospatial applications for artificial intelligence, is conducting its first temporal challenge with new partner Planet.

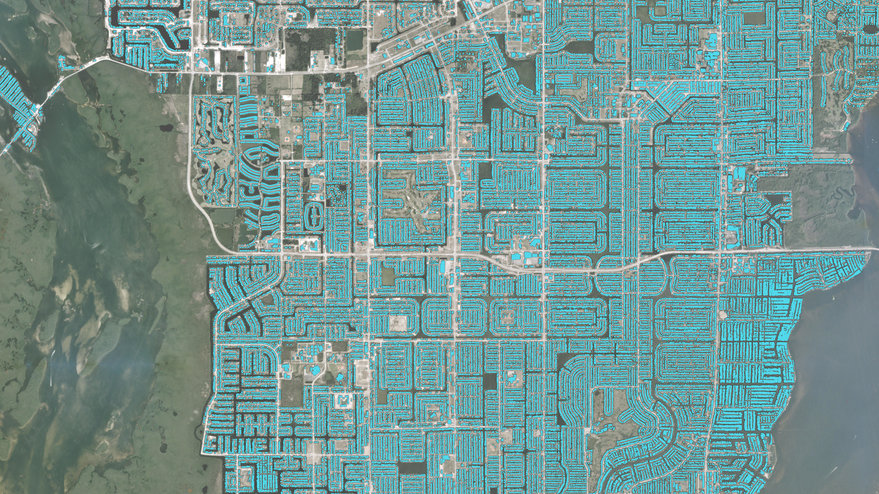

Competitors in SpaceNet 7 the Multi-Temporal Urban Development Challenge will have two months starting August 31st to devise change-detection algorithms to track building construction over time. Winning entries are scheduled to be announced in December at the virtual Neural Information Processing Systems conference.

For the challenge, Planet is supplying monthly imagery over a period of two years for more than 100 locations covering 40,000 square kilometers on six continents.

“SpaceNet is a precursor to open-sourcing geospatial data to the community,” Jonathan Evens, Planet machine learning and Basemaps product manager, told SpaceNews. “We want to be part of that.”

In addition, if Planet wants to promote development of new methods to monitor change in its data, SpaceNet is “an amazing conduit for that,” he added.

Increasingly, satellite constellations offer customers frequently updated imagery of various sites, prompting demand for machine learning and computer vision algorithms capable of highlighting changes in the geospatial datasets.

“We’re tracking urban development explicitly at the [building] footprint level,” Ryan Lewis, SpaceNet general manager and In-Q-Tel senior vice president, told SpaceNews. “It’s a very challenging task” that has important applications for disaster response, monitoring population change and the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals, he added.

Since SpaceNet was formed in 2016 by Maxar Technologies, In-Q-Tel’s CosmiQ Works and NVIDIA Corp., the nonprofit has created an online repository of free satellite imagery and labeled training data to encourage development of algorithms designed specifically for remote sensing data. SpaceNet shares data through Amazon Web Services.

SpaceNet now includes its founding members as well as Planet, the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency, the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Geoscience and Remote Sensing Society, Topcoder, a Wipro company, Amazon Web Services and Capella Space

While unveiling its latest challenge, SpaceNet leaders also are taking stock of the organization’s accomplishments.

People in 82 countries have downloaded SpaceNet datasets. Over four years, the nonprofit has received 3,000 submissions to its data-science challenges from people in 34 countries.

SpaceNet, a project conceived by Lewis and Todd Bacastow, Maxar director and SpaceNet Advisory Council co-chair, “turned into a global effort that has a pretty substantial following in all the areas that you might expect that are focused on [artificial intelligence] research and computer vision,” Lewis said.

When SpaceNet formed, obstacles confronting researchers who wanted to apply artificial intelligence to geospatial datasets included a lack of available data and data-licensing challenges.

“We wanted to advance the state of the art for our industry but also to broaden exposure and get excitement from the broader technology community,” Bacastow said.

By clearing away some of the obstacles, SpaceNet has revealed “broad hunger within the space community to make these resources open to serve as a foundation for future product development,” Lewis said.

In addition, SpaceNet challenges have attracted people who do not usually work in the space or aerospace industry. Some of the people participating in SpaceNet challenges previously worked primarily with medical or automotive datasets, Lewis said. “That’s been a huge sign of success,” he added.

Over the years, SpaceNet has continually heightened the technical complexity of each challenge by increasing various elements like the geographic diversity of datasets or by asking competitors to detect new objects, like roads as opposed to buildings.

For its sixth challenge, SpaceNet created an open-source dataset that combined Capella Space airborne synthetic aperture radar imagery with Maxar WorldView 2 electro-optical imagery. Competitors were asked to automatically identify building footprints.

“We want to keep pushing novel datasets and difficult challenges, because that’s what we’re hearing researchers, government, academia and companies want us to,” Lewis said. “Hopefully can serve as an early indicator for them of what will eventually come down the road in their product development.”