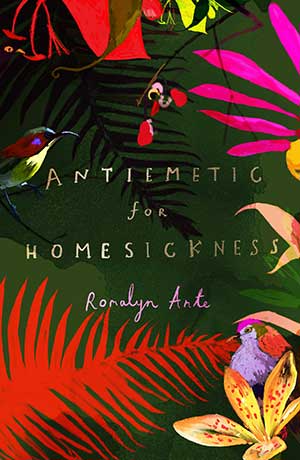

I was lucky to meet Romalyn Ante when I was invited to read at a virtual event organized by R. A. Villanueva and hosted by Books Are Magic in August 2020. Ante was the guest of honor at the event, and her debut poetry collection, Antiemetic for Homesickness, struck me as incredibly powerful and timely. Working for the National Health Service, Ante shows her reader what it is like to be a Filipino nurse in the UK. Not only does this collection explore sickness and healing—something that was and continues to be on all of our minds during the pandemic—it also explores the conditions of poverty and desperation that cause Filipinos to work overseas, as well as the all-to-familiar difficulties of family separation, homesickness, and the struggles with racism and assimilation that Filipinos in the diaspora experience. Published during a global pandemic and a period of racial reckoning, this dazzling collection speaks to the present moment and offers a unique perspective on sickness and homesickness in the Filipino diaspora. After hearing and reading Ante’s poems, I wanted to learn more about her life and her writing process. In May 2021 I corresponded with Ante about her work.

Marianne Chan: As a Filipino person in the diaspora, I found Antiemetic for Homesickness relatable and incredibly moving. Can you talk about the genesis of the book?

Marianne Chan: As a Filipino person in the diaspora, I found Antiemetic for Homesickness relatable and incredibly moving. Can you talk about the genesis of the book?

Romalyn Ante: Thank you, Marianne. I came from a family of nurses and healers. My paternal grandfather is a manghihilot (village shaman and chiropractor). My mother is a nurse and so is my auntie. Eventually, my sister and I became nurses as well. When I was a student nurse in the UK, I always looked for books about nurses, especially migrant nurses, but could not find one anywhere. It is a shame considering that the US and UK health-care systems rely heavily upon migrant nurses. In fact, Filipino nurses share the largest proportion of migrant nurses in the US and the UK, so I was disappointed not to find any literature about our community. But nonvisibility does not equate to nonexistence; I believe my urge to make the narratives of nurses known in the UK landscape is my reason. Antiemetic for Homesickness is also a political act for me. It attempts to humanize nurses, because I believe we have been undervalued and reduced to our functions.

Chan: The first poem in the collection is called “Half-empty.” It responds to Prince Phillip’s joke about the Philippines, which is the poem’s epigraph: “The Philippines must be half-empty; you’re all here running the NHS [National Health Service].” Cleverly, the poem takes the form of a description of a medicine called “Migrationazoline,” and it counters Prince Phillip’s comment by showing the reader the conditions of poverty and desperation that result in Filipinos leaving their home country to work for the NHS. How did you develop the form of this poem and other experimental forms that appear in this collection?

Ante: I don’t have any formal creative-writing-related education, and I write in English as a second language. However, I believe that nursing does not only exist in the field of science; it is a bachelor of arts, in a way. Nursing taught me to pay attention. It taught me self-awareness and awareness of others, of the world. I am thankful that the profession taught me to become a poet. When I decided to write AfH in 2017, I knew that I must see the world not only with a poet’s eyes but also with a nurse’s. I must observe the tiniest of details such as a drop in blood pressure, a slight rise in temperature, what I have in my hands, what I need to discard. Suddenly, everything around me becomes a source of poems and forms.

Nursing taught me to pay attention. I am thankful that the profession taught me to become a poet.

Chan: Many Filipinos, particularly women, leave their families in the Philippines to work abroad. Antiemetic for Homesickness explores the loneliness of the person leaving their family to work overseas as well as the loneliness of those left behind. I know that you’ve experienced both sides of this migration trend. Can you talk about how your own personal experiences shaped the content of these poems?

Ante: The book is informed by my experiences, and it really helped with the formulation of its contents. However, I also needed to input a lot of imaginative energy in the book, as I know poetry is different from memoir. There is a sequence called “Tape Recordings for Mama” in the voice of a left-behind child in the book; each section is spread out from the beginning of the book toward the end. These act like ligaments that hold the book together, which is also my metaphorical way of saying how language holds the relationship together, a relationship severed by distance and time. I think more than anything, the book is a reflection of an emotional truth. I wanted to show not only the advantages of migration (i.e., having more money, a better future) but also the price we pay for leaving.

Chan: The voices in this collection sometimes feel particular, exploring one speaker’s specific experiences and relationships with her family. Other poems seem to be speaking to or for a larger group. Can you explain how you approached the voices in these poems? How did you balance one specific experience with the general experiences of the many who leave and are left behind?

The book does not sing in iambic pentameter; there are a lot of playful, “broken” lines.

Ante: Li-Young Lee said a poem is like a score of the human voice. Because I write from a point of view that is informed by my nursing life, I wanted my work to be as authentic as it can be. I wanted to bring out the voices of migrant nurses in the book not only using the forms that are appropriate for “us,” but also in a manner that reflects us. Coming from a family of migrant nurses, I grew up hearing our accents, the fracture of our statements and sentence constructions, which metaphorically reflect the fracture of ourselves as people in the diaspora. The book does not sing in iambic pentameter; there are a lot of playful, “broken” lines. But the most important thing for me was for the poems to be “transparent,” and for their emotional truth to come out. That is why I am so happy whenever a Filipino (from any part of the world) reads the book and tells me how “proud” they are of it and how it helped them process and overcome what they’re going through as migrants. This makes me humbled by my own migrant and working experiences.

Chan: A poem that I keep returning to in your collection is “A Manananggal Replies to a Child.” The manananggal is one of my favorite Filipino mythical creatures, one whose upper body separates from her lower body at night when she goes hunting. You use the manananggal as a metaphor for a mother leaving. I think this poem speaks to the criticisms that women, in particular, encounter when they choose to leave their families behind in the Philippines to find work overseas. In addition, the poem seems to appreciate the strength and power of these women. Did you want to make a feminist statement in this poem? Did you always see the manananggal as a kind of feminist figure?

Ante: Yes, you’re definitely right. Women have often been silenced when they do something that seems “abnormal” or “monstrous.” When a mother leaves, she is seen as someone who “overlooks” or “forgets” the very essence of being a mother, which is to take care of her family. But migrant women have been taking care of their families for decades, from a distance. My mother left our homeland (and everything and everyone in it) so many times. She did not leave for her own personal gains and growth; she did it for the whole family. She chooses to sacrifice for us. And I think sacrificing is a very brave and honorable act. And aren’t those the qualities of feminists? To be bold, brave, and honorable? Despite some people seeing us as monsters?

Women have often been silenced when they do something that seems “abnormal” or “monstrous.”

Chan: In an interview you did with Alice Hiller, I read that you began writing poetry as a way to process your experience as a nurse. I also use poems as a way for processing experiences. In addition, I often think of poems as a mode of inquiry. For me, poems have always allowed me to ask and, perhaps, to answer questions. What questions did you have as you wrote Antiemetic for Homesickness? What do you think you learned by writing these poems?

Ante: I write poems to process my experiences but also to transform. I would echo Denise Levertov in her essay “Talking to Doctors” when she says that poetry is not just a matter of expression or expulsion. It is also a matter of transformation. I realized, especially after writing the book and getting all the positive comments from my readers, that in crafting, the poet and the readers become transformed too. Before Antiemetic for Homesickness, I wondered why there is so little known about Filipino nurses here in the UK. One person even asked me (after telling him that I am a Filipino), “So . . . does that mean that you’re from Korea?” I wanted the book to be an instrument that shows our story. I wanted the voices in the book to reflect the voices of migrant Filipino workers. Of course, I cannot say that I speak for the community of migrant Filipino workers. Rather, I’d like to say I speak with them.

Chan: You and I both released a debut poetry collection in 2020, a difficult year to promote a poetry collection. I’ve been horrified and saddened by the disproportionately high number of deaths from Covid-19 among Filipino nurses in the US and the UK. In addition, the rise in racial violence toward East Asians has made this year even more challenging. So, my question is: How are you? How was this year for you, both in terms of sharing your book with the world and also working as a Filipina nurse in the UK? How do you see your book as speaking to the present moment?

Ante: It was a shock for me when my book publication coincided with the start of Covid-19. One may think that this is an opportune time: a book by a Filipino nurse, about Filipino workers. But just like you, Marianne, it was a real struggle for me too! You know: it was so difficult not to be able to promote our books and not to be able to communicate or interact with our readers in person. Some people think I wrote the book for Covid, or that the book is about Covid. This confirms my theory that nursing will always exist in time. Because nurses will always be needed. However, this is also an example of how oblivious some people are when it comes to the narratives of migrant Filipino nurses. We have been leaving our families, we have been struggling, we have been discriminated against decades before Covid-19.

Chan: What are you working on now?

Ante: I have quite a lot of readers who contacted me and asked if I can write nonfiction based on my or my mother’s real story. I think there is something more sacred in writing a memoir or an essay. We are laid bare to the readers, but we are also more able to claim the wounds that strengthen us. So, I have been writing a series of memoir-essays, and I hope they will find their way to publication in the near future.

May 2021