A new double-layered fabric inspired by the black skin and white fur of polar bears uses heat radiated from the Sun and indoor lighting to trap and maintain warmth. The fabric could be used to make “personal climate” textiles that weigh 30% less than cotton for a given area and keep wearers warm at temperatures 10°C colder.

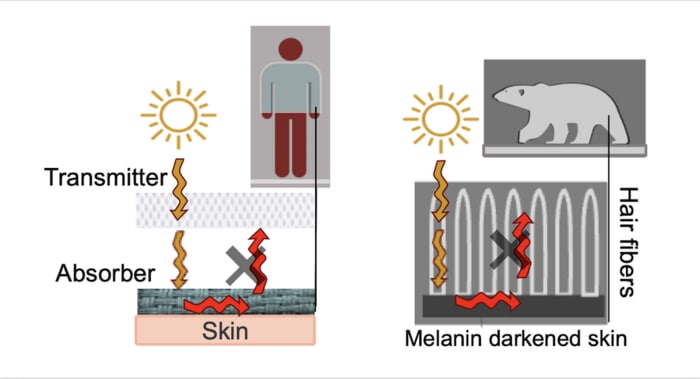

Although fabric technologies have advanced significantly in recent years, a truly thermoregulating textile is still lacking. The new material, created by researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the US, partly addresses this gap by pairing an outer layer that transmits visible light with a base layer that absorbs it while reflecting light at infrared frequencies.

“The outer layer receives light from the Sun and then transmits this light down to the base layer,” explains team leader Trisha L Andrew, a chemist and wearable electronics expert at Amherst. “This is much like how a polar bear’s fur, which is essentially a natural fibre optic, conducts sunlight down to the bears’ skin. The skin absorbs the light, heating the bear.”

On-body greenhouse effect

Polar bears evolved their combination of dark skin and white hair to keep warm in their icy habitat by selectively reflecting, absorbing or transmitting radiation across the visible and infrared parts of the electromagnetic spectrum. Though the precise details of the mechanism are not well-studied, scientists believe that low optical density (light-coloured) insulating features such as white fur help polar bears achieve an on-body version of the greenhouse effect.

Somewhat counterintuitively, this white fur transmits much more radiation to the bear’s skin than darker hair would. Indeed, the “solar utilization factor” – a ratio of heat utilized to total solar heat gain – for polar bears ranges from 10% to 50%. This high utilization is further enhanced by the polar bear’s skin, which is rich in melanin – a dense biopolymer made up of conjugated units that have a high refractive index and absorb light at a broad range of wavelengths.

Similar thermoregulating surfaces are also present in other animals, including species of moths, butterflies and birds that have adapted to live in cold but sunny climates. These surfaces selectively absorb light in the visible and near-infrared part of the spectrum (where photothermal heating occurs), while reflecting it over the infrared range, where objects spontaneously radiate heat according to Planck’s law.

Some artificial materials also regulate heat in this way, and researchers have previously made textile coatings from optical materials such as MXene, carbon nanotubes and silver nanowires. However, the resulting fabrics did not contain a visible-transmitting outer layer to prevent heat from being lost to the wearer’s surroundings.

An alternative to inorganic or carbon nanomaterials

In designing their new base layer, Andrew and colleagues eschewed inorganic or carbon nanomaterials in favour of nylon coated with a dark polymer called poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene), or PEDOT. This polymer is particularly well-suited to making textiles and has a high optical density while remaining lightweight and flexible.

To test the new thermal textile, the Amherst team used skin and solar simulators. These measurements showed that when the textile is exposed to a moderate light intensity of 130 W/m2, it keeps its wearer just as warm as cotton fabric would – and at temperatures that are 10°C colder – while weighing 30% less.

‘Janus textile’ could keep you warm and cool you down

“Our polar bear fabric could be very useful for managing space heating, which consumes huge amounts of energy, in a more energy efficient manner, by heating people indoors using ambient lighting instead of room heating,” Andrew tells Physics World.

“By focusing energy resources on the ‘personal climate’ around the body, this approach could be far more sustainable than the status quo,” adds study lead author Wesley Viola.

The Amherst team is now exploring how to achieve on-body radiative cooling, which will be vital as climate change pushes temperatures higher and heat waves become more common even in temperate regions.

The new thermal textile is described in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces.