If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I wish I remembered exactly where my dad got the 1992 Royal Rumble tape. I imagine it was from the packaging factory in the Toronto suburbs where he worked for most of his life. We couldn’t afford to order the pay-per-views, so we relied on bootlegged copies from his co-workers for the majority of our wrestling videos. We collected others by recording WWE (then WWF) Saturday Night’s Main Event off the TV each week. Sometimes, we’d rent a show from the local video store, set up two VCRs, and record it onto a blank VHS. I was six or seven years old at the time and my mom worked the afternoon shift as a custodian on an assembly line, so dad and I would watch these recorded tapes each weeknight. Dad, exhausted from his own laborious day shift, would often fall asleep on the couch beside me, while I repeatedly poured over the familiar matches. This was as close as he ever came to reading to me before bed.

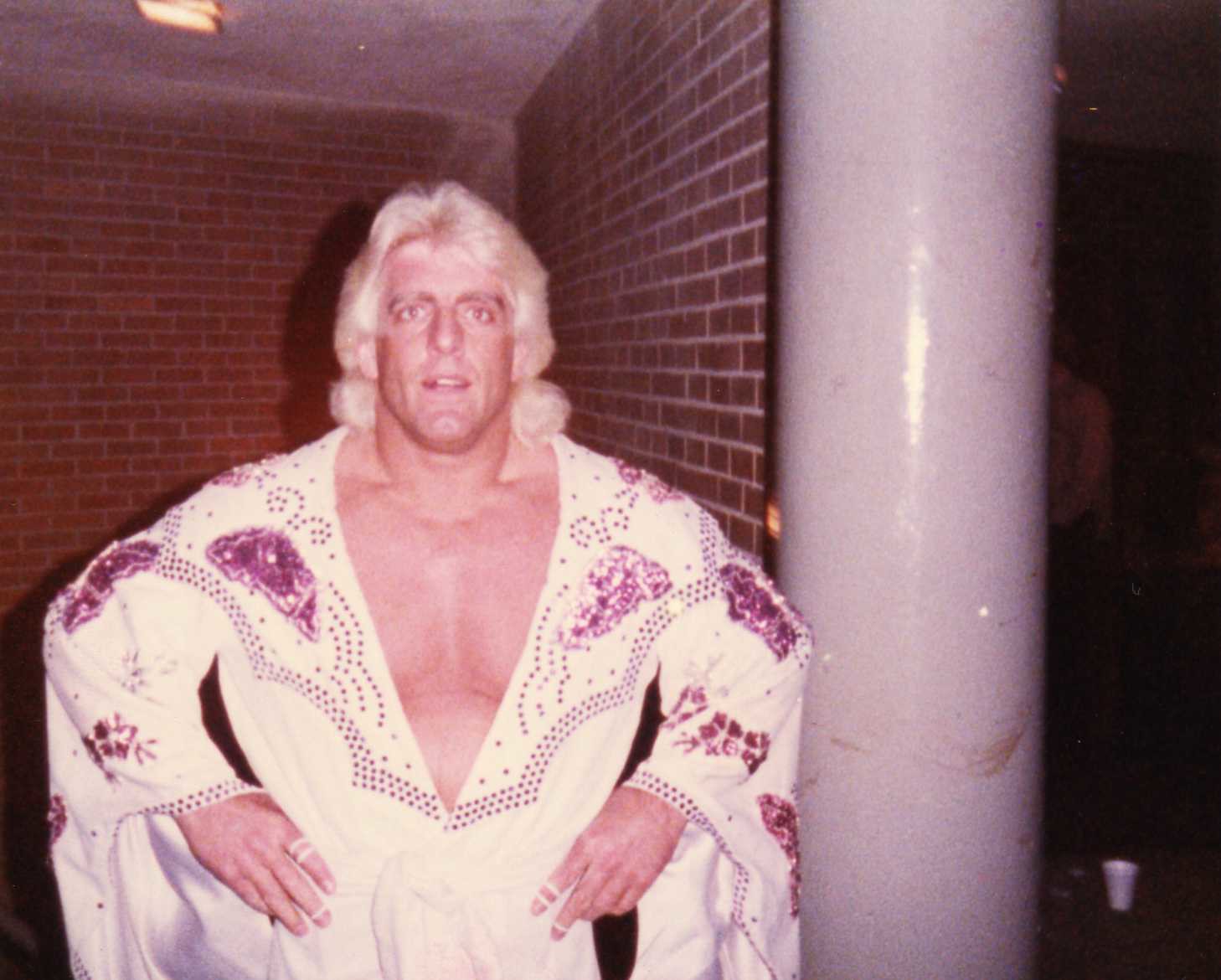

Wrestling was always on in our house, but the 1992 Royal Rumble was special. We watched this tape together often, each time pretending to be unaware of the outcome. We feigned surprise every time the villainous Ric Flair weaseled his way to a victory in the 30-man over-the-top battle royal to win the championship belt. Dad cheered for his cheating antics while I faithfully rooted for the wholesome Hulk Hogan to regain the title. Dad played heel to my babyface, illuminating the struggle between good and evil to me through wrestling.

Why—almost 30 years after the 1992 Royal Rumble and sixteen years after my dad’s death—am I still watching professional wrestling?

Every January, during the build up to the annual Royal Rumble, I think about my dad, who, like a wrestler who lived too hard, suddenly passed away in 2005. I also consider Flair, the renowned dirtiest player in the game, and what my dad tried to teach me through the Nature Boy’s elusive ways. Above all else, I contemplate a larger question. Why—almost 30 years after the 1992 Royal Rumble and sixteen years after my dad’s death—am I still watching professional wrestling?

My grandpa was perpetually disappointed when he caught dad and me watching wrestling matches. He ridiculed our passion, referring to it as “a waste of time.” He mocked us for “watching these naked men dancing around” and never missed an opportunity to tell me it was “fake,” no matter my degree of obsessive belief.

Grandpa, a stout three-piece suit-wearing Punjabi Sikh who matched the colors of his tie and turban, recited the daily Sikh prayers loud enough for the entire house to hear every morning. He specifically targeted me before school, encouraging me to repeat the prayers in the shower, while I got dressed, and during breakfast. The religious texts themselves were inaccessible to me, as they were often bound in lavish cloths and kept in the most elevated places, usually the top shelf of a closet in the highest room in the house. Even if I could have reached the scriptures, I wouldn’t have been able to read them, because they were written in Punjabi or another dialect that appeared simultaneously foreign and familiar. As a first-generation South Asian growing up in Canada, I recognized the words but failed to understand the non-Romanized alphabet that formed them. Without complete physical or mental access to the scriptures, my grandpa resorted to dictating and translating them to me. Roughly, these sacred texts described a “formless” yet “all-pervading” God who was equally present and obscure.

Despite Grandpa’s insistence, Dad never adopted religion at his beckoning. He let grandpa force the prayers on me, but I never heard dad repeat them publicly, except for an occasional sarcastic waheguru (oh God). Even at Grandpa’s funeral in 2004, one year before his own death, Dad silently listened to the ceremonial prayers rather than reciting them with everyone else.

During particular bouts of religious fervor, my grandpa would advocate for me to grow my hair and wear a turban like a true Sikh. “Your father didn’t listen to me, but there’s still time for you,” he said. I kept delaying, maintaining that I would consider formalizing my religious devotion next year, and then the year after that.

Unlike the abstract prayers, wrestling had narrative arcs that informed my morality.

My elementary school days consisted of prayers in the morning and wrestling in the evening. Scripture and mythology. Absolute truth and fiction. I always preferred wrestling because I understood it. Unlike the abstract prayers, wrestling had narrative arcs that informed my morality. I learned never to look at another man’s wife from the Hulk Hogan-Miss Elizabeth-Randy Savage love triangle, when Savage infamously accused Hogan of having lust in his eyes and in his black heart. The Hart Foundation taught me how to love my siblings unconditionally, despite the family rivalries, jealousy, and outside interference from those trying to split us apart. I discovered that death is inevitable for everyone—except for the Undertaker, because you can’t kill what’s already dead.

Despite Grandpa’s rumblings, Dad continued to be an advocate and my tag team partner for watching wrestling. The extent of his fascination is confirmed in a collection of family photos that I recently revisited. In one, I’m maybe four years old, resting in my dad’s arms, holding my chubby cheeks to his youthful face in front of a “Rowdy” Roddy Piper poster. In another poster, my dad stands alone with his hands crossed in front of his slender frame, in faded jeans and a blue crewneck sweatshirt, in front of Million Dollar Man Ted DiBiase with Virgil and the Honky Tonk Man. The last photo is of my mom and dad sitting together on the bed. Dad has his arm loosely wrapped around Mom, the most affection I ever saw between the two. Their intimacy is awkwardly mirrored by the portrait in the background of Macho Man Randy Savage and Miss Elizabeth: wrestling’s royal couple, often called “the match made in heaven.”

What strikes me about the posters in these old family photos is the nuanced choice of performers. These weren’t the titans of wrestling at the time: Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant, the Ultimate Warrior. Instead, it was the intercontinental champions, the exaggerated American gimmicks of wealth and music, and a Canadian pretending to be an unhinged kilt-wearing Scottish wrestler. These were immoral anti-heroes that illuminated the goodness of the megastars that I adored. Dad lived the heel gimmick to my babyface as he specifically sought out these posters and then convinced my mom to pose with them.

As an immigrant from a small agricultural village in Punjab, India with minimal English skills, my dad used wrestling to communicate with his co-workers. If wrestling was my first fiction, it was potentially a language for him, a way to assimilate at work and connect with life in a foreign country. Suplexes and submissions replaced reading and writing. Maybe he was indoctrinating me so I too could engage with my peers at school—or perhaps wrestling was his language to connect with me.

Wrestling was our shared education of North American values, our common fiction.

Wrestling was our shared education of North American values, our common fiction. Our fandom and understanding of the world grew together. We never explicitly discussed sex or sexuality, but we watched the raunchy and distasteful segments with Sable and Sunny on Monday Night Raw. That was as close as we got to “the talk.” We never discussed our Indian immigrant identities, but proudly sided with Canadian icon Bret Hart during his heated nationalist feud with Shawn Michaels in the late ‘90s. We were proud Canadians because our own Hart was the best wrestler in the world and morally superior to Michaels. We never talked about depression or death, but we saw Mankind manically pull his hair out in a boiler room while grieving for a lost childhood before burying another man alive. We had all of life’s sensitive conversations in silence, through the fictitious portrayal of morality in the wrestling ring.

This was no different than a father reading to his kids, indoctrinating them into the fandom of his favorite sports team, or encouraging them to follow in his professional footsteps. All those formative moments occurred for me through a single medium. Professional wrestling was my simultaneous introduction to fiction, sports, and the grown-up world. Although Dad never said much, the in-ring lessons were self-explanatory based on what we watched together. Sergeant Slaughter was to blame for America’s war in the Persian Gulf and that was why Hulk Hogan had to defeat him at Wrestlemania VII. Nobody liked paying taxes because Irwin R. Schyster (IRS) was a greedy and corrupt heel just like the internal revenue service. Ravishing Rick Rude—with his mullet, thick mustache, and muscular body —was a real man because the women in the audience gushed over him every week even though he brutally insulted their hometowns.

Dad could never be compared to wrestlers capable of cutting a stirring 10-minute promo that left the audience anxious for their next match. He was quiet and sensitive, which is why I think he was drawn to loudmouth wrestlers like Flair and DiBiase. They were obnoxious and cocky, the opposite of his reserved, unambitious persona. He worked in the same factory for decades, rarely bought new clothes, drove his cars until they halted on the side of the road, and hated any disruption in his routine. He was content with the first variation of immigrant life he found and never felt the need to expand it. He didn’t seek additional knowledge about the world. Instead, he survived in it as he saw it: a confined ring with ropes and turnbuckles. Wrestling, as both a fiction and language, was his simplified introduction to life abroad and so it naturally became mine as well.

I absorbed wrestling before ever reading a book, watching a movie, or adopting a God.

In Grandpa’s absence, Mom has gladly inherited his role when she catches me watching wrestling alone. “This is what your father did his whole life and now you’re going to do it too,” she says, condescendingly. I used to rebel against her resentment, trying to explain the rooted life lessons from the fiction that shaped my childhood. I absorbed wrestling before ever reading a book, watching a movie, or adopting a God. It always made sense to me because it made sense to my dad. But I no longer fight back against Mom’s cynicism. Instead, I too watch quietly now, letting the fictional conflicts in the squared circle restore memory and meaning.

Wrestling occupies the silence around me. Each match mirrors the last one, and the one years and generations before that. Good versus evil. The story never changes. The repetition evokes nostalgia for a time when tapes could be rewound, Dad slept by my side, and praying was a mandate.

No single wrestler, feud, or moment keeps me engaged with wrestling. Rather, it’s the harmonious sequences—the sleeper holds, elbow drops, and leg locks—that form a language to converse with the past, to seek answers to questions that I never asked. Dad’s silence has transformed to absence, yet I still hear echoes of his sentiment each time a body crashes onto the mat and a loudmouth heel mocks his babyface opponent. I don’t need to imagine Dad’s voice, because he wouldn’t have said anything—only fast forwarded to the next match.