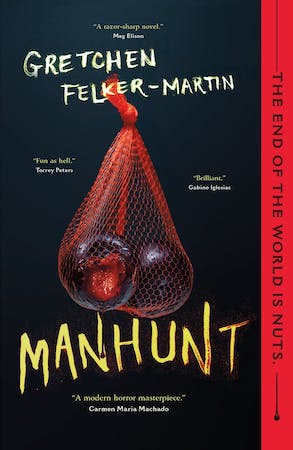

Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Manhunt is a revelation: a gory, prickly horror novel unflinching in its violence but deeply humane as well. The book depicts a world ravaged by a plague that turns all people with testosterone in their bodies into feral, matted-haired monsters. But in contrast to the growing canon of cis-normative gender-apocalypse fiction, Manhunt centers its story on trans women and their allies. The most present threat through the book isn’t the infected, but a roving gang of TERFs who have scapegoated trans women during the plague, hunting them from military strongholds and war caravans.

Felker-Martin’s novel—which features estrogen synthesized from harvested testicles, J.K. Rowling dying in her castle, and queer sex as tender, fraught, and intimate as it is in real life— has already made a splash with readers and critics; it’s now in its sixth printing and has been widely lauded. Through this positive reception, many of the reviews around the book have focused on its handling of TERFs and the violence endemic in the book. However, as a trans woman myself, what I responded to the most—and what I’ve seen the least in coverage of so far—was the shared love between queer people Felker-Martin emphasizes, the shared, complicated love between trans women.

I talked to Felker-Martin recently over Zoom about this love, community, queer lineages within Manhunt, and more, the early afternoon light dappling across the computer screen. Ultimately, our conversation kept circling around the importance of survival and care—within the world of the book, and even more, without.

Zefyr Lisowski: First of all, your novel is so brilliant! One of the things I think it’s most effective at is juxtaposing these intimacies between intense horror and trauma and the intimacy required to navigate in horror’s wake—even as that intimacy may in turn traumatize, too. As you were writing this book, how did you cultivate that intimacy within yourself? What comforts besides the book—if writing the book was a comfort—did you have?

Gretchen Felker-Martin: Writing the book was a comfort in the same way that knocking a wall down with a sledgehammer is a comfort—you’re not necessarily going to feel physically good afterward, but you’ll have achieved something at least. It’s just internal in this case.

Writing the book was a comfort in the same way that knocking a wall down with a sledgehammer is a comfort.

I think my friends and my community were my real comfort while I was writing this book. If I hadn’t had people around me, if I hadn’t had the kind of love that these characters are so hungry for, it would have been much, much harder to get through this. And then, of course, it was a huge challenge, especially in lockdown, to be so physically isolated. You know I started writing this in late 2019, really just 4 or 5 months before the pandemic hit, and it was surreal to go through that shift.

I think that being in the emotional space of this novel and having that as the backdrop to my life definitely did crack me open a little wider. I started a few relationships while I was writing and editing it, and those have been very vulnerable open connections. I’m not sure they would have been to the same extent had I not been so immersed in that headspace.

When you’re working on something like this, you have your hands in your own guts, and like you said that is both revelatory and potentially healing, and also just by nature painful. You can’t be that intimate with something without it hurting you.

And the only things that can hurt you are things that are that intimate.

ZL: That intimacy really, really shows through.

GFM: Thank you so much. I’m really glad you enjoyed it. I’m a tremendous fan of your critical writing. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve recommended The Girl, The Well, The Ring to people.

ZL: Thank you so much! That really means a lot. The book has such a rich sense of geography throughout, but especially in the second half, the locations became a lot more centralized: now they’re in the compound, now they’re in the ruins of Seabrook and Boston. That seemed filmic to me, in how it laid out space and then narrowed in. Because I know that you’re also a movie critic, did films impact your structuring of the book?

GFM: Well, like you said I’m a huge movie buff. I’ve certainly spent as much or more time watching movies than I have reading books, and to some extent I would say I’m more familiar with the structure of films and the techniques that directors typically use for things like building tension or establishing romantic connection than I am with the equivalent structures in literature.

So to an extent I think it’s inevitable that that’s the language I would use when it came time to write something that I wanted to have a little broad appeal. That’s the wrong word for Manhunt, but it’s definitely more accessible than the books I’ve published myself, which are medieval horror and extreme trans body horror. Much more niche.

I wanted the first portion of the novel to really root the reader in the setting. I felt that was important to understanding it. Whether or not they had any experience personally with New England, I want to at least give a sense; then from there, you don’t have to retread that material. You can just sketch. In the same way that a film will spend a lot of time on exposition or establishing shots and then move on to simultaneously broader and more personally intimate material, that’s also how I work.

ZL: That is definitely visible! I grew up in the rural South, which is not New England. But I think rural areas that are decimated by poverty, especially in the US, are all the same—

GFM: It’s pretty universal.

ZL: So I recognized a lot of rural North Carolina there as well, through the specificity of New England.

GFM: That’s so cool!

I wanted the first portion of the novel to really root the reader in the setting. I felt that was important to understanding it.

ZL: Going back to the relationship between intimacy and violence: there are ways in which that intimacy is weaponized more explicitly—I’m thinking about the tenderqueer house that kicks out its trans woman members shortly into the plague—but it also appears in smaller, more granular moments as well.

More specifically, I’m thinking about the relationship between Fran, a trans woman who grew up wealthy and passes, and Beth, who did not and doesn’t. Beth is torn up by both of these things and also hurt by Fran more generally, in ways that definitely resonated with my own experiences but also bucks at the idea of solidarity—even t4t solidarity—as something that can exist outside of existing hierarchies of privilege.

I think the book is better for going there, but what was the significance of writing into this tension for you? Negative affect in trans writing more generally is so discouraged. Did you experience pressure, either internally or externally, to shy away from it?

GFM: Yeah, I don’t give a shit about that pressure. Those people mean less than nothing to me. I think that if you’re going to talk about queerness with a sunny cast to it, where the fuck has your head been for the last 100 years?

We live in a world that’s actively trying to genocide us. We live in a world where we’ve all been brought up to hate ourselves and each other. When you put a bunch of traumatized queer people together, they do not magically form a perfect family. They are fucked up! We fucking hurt each other and ourselves all the time, and I think that when you acknowledge that it becomes so much more beautiful and special that we still put in all of that backbreaking, miserable work to love each other. Because it’s not easy.

That’s what’s important to me. If I wrote a book about a queer community or the concept of queer community, and I didn’t show how hard it is, and how deeply rooted in our own hearts as individuals those prejudices are, I would feel really ashamed of what I’d done. I would feel dishonest. Especially with the tension between Beth and Fran. Beth is so disaffected by her connection to Fran, who frequently treats her thoughtlessly, and who enjoys all of these privileges in the world, has all these abilities to move that Beth doesn’t.

When you put a bunch of traumatized queer people together, they do not magically form a perfect family. They are fucked up!

That’s something that I feel acutely. I’m very tall, and very fat and have always been an extremely visible person, which has only increased by orders of magnitude as I’ve come out in various ways. I think that experience is what I’m interested in communicating in part. I want to create these voices that might speak to readers and say like, ‘Hey, this fucked up thing that you are going through? This is actually an experience that other people share. These thoughts that you have in your head, that you feel like you can’t communicate, because it would be bad or homophobic, or whatever? Other people are having these thoughts too, and if we share them, maybe we can do something about them.’

ZL: Getting to this place of not just catharsis for the sake of catharsis, but catharsis in terms of moving things forward with regard to how we love each other better.

GFM: Yes. I try to be generative in the way that I think about queer community—and queer community itself is is such a an elusive thing. You know so many people when they say it, they mean every queer person in the world, or every queer person online. And those are both nonsense. I’m not in community with the people who don’t live around me. My community is my friends and my lovers and my acquaintances, and my community includes people that I’m not wild about. It’s about actions, connections, daily patterns of existence. But community is not about being happy. Community is about taking care of each other.

ZL: Looking at your book, I see it in this lineage with things like Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, which I know you quote in the book. I see it in conversation with Kai Cheng Thom’s work, especially her nonfiction like I Hope We Choose Love. Porpentine Charity Heartscape’s Hot Allostatic Load came to mind in your work’s discussions of inner-community violence.

What writers, or even people who aren’t writers, do you feel these ideas are in conversation or community with?

GFM: Well like you said, for sure, Torrey Peters is a friend of mine. She’s the last name thanked in the acknowledgments, and I’ve been enormously flattered every time someone brings Manhunt up in connection to Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, which is obviously a huge influence, and also just one of my favorite novellas. Torrey is such a good writer. I really have deep admiration for her craft and for her ability to spin these worlds that are all about and for trans people. I think that’s a very special thing and it’s tough, too, when you’re a trans creative.

I think a lot of us feel very hinky about getting intimate with our existences, about communicating the granular in-world stuff about being trans, because it could be alienating to other readers, or make other trans people mad at us, or whatever. But Torrey is a big part of my immediate literary lineage.

Porpentine is probably my favorite current novelist, and Psycho Nymph Exile is probably my favorite modern novel, and similarly, you know, it’s this book that’s very vested in the world of transness that is not interested in pandering to any other audience or in softening or explaining this world.

I haven’t read Kai Cheng’s work, but I do like her very much. I think she’s just a tremendously principled and kind person.

In other terms, I would say that I see myself generally as a writer, and Manhunt in particular, as a descendant of paperback horror queens, like Melanie Tem. People who want to gross the reader out as lyrically as they can get away with, who wanna play around in this sandbox full of guts.

And of course I grew up in New England. I’m a huge Stephen King Fan, and always will be, warts and all. Manhunt owes a lot to that kind of pulp.

ZL: Yes! As I mentioned to you, the experience of reading the book immediately transported me back to elementary school, sneaking Stephen King’s books out of the library with my child’s library card.

GFM: That’s what I want. Man, I remember when I was writing this book, I said, ‘God damn I hope this makes some kid just into a total freak.’ Like, some little weirdo who gets a hold of this book when they’re 11 and just goes completely off the deep end. Because you know that was us absolutely, and it’s such a special thing.

In other terms, I would say that I see myself generally as a writer, and Manhunt in particular, as a descendant of paperback horror queens.

ZL: I love seeing all the positive attention Manhunt’s been going through—it’s in its sixth printing now!— but also there are these two incredibly stupid pile-ons that happened: when the book was announced and certain people on Twitter called it transphobic, and then when the TERFS found out about the J.K. Rowling bit. Is there anything around those specific incidents that you wanna talk about?

GFM: I mean, you can’t plan for stupid. Some people go through life looking for a tweet to get mad at, and that is just not something you really have any control over. I think that it’s an interesting social phenomenon that predates the Internet, but has been just honed to an absolutely merciless edge by it, because now, of course, one person’s manufactured outrage can reach millions of others.

The first controversy was interesting. You know, Manhunt is set in this world where a virus has transformed anyone with enough testosterone in their body at the time of infection into a ravenous rabid monster, and you would think that cis men would be upset about this. But I don’t think that I’ve ever received a single bark of complaint from any cis dude reader. Invariably they go, ‘oh, man, that cover made me wince. Cool book.’

However, a lot of a certain type of trans masc seems to get really, really worked up and offended about this book—mostly from a single tweet, explaining the premise. Some people have apparently read the book and gotten mad—that’s fine. I didn’t set out to write something that wouldn’t be contentious, or that would please everyone. I don’t imagine I will ever do that, nor would I want to, but it does get tiring enduring all that from your own community—to use the broader sense of the word community here.

I think there’s a profound unwillingness among certain groups of trans people to give trans women the benefit of the doubt, and a desire to seize upon any opportunity to declare one of us persona non grata. Once that’s happened, there’s no winning. There’s nothing you can do except take it, block them, and move on.

I didn’t set out to write something that wouldn’t be contentious, or that would please everyone.

I don’t know that I had much to say about the TERFS. I mean, that was inevitable, and to an extent I knew what was gonna happen with the book. That actually happened because Jesse Singal retweeted excerpts of the book to his fans, because he found me calling him a half-pint Goebbels and got really fucking bent out of shape about it. I’ll just repeat that here: Jesse Singal, you’re a piece of shit fascist.

I think that it’s deeply unfair that if you want to be a trans woman in a creative field, though, that this is really the floor for experiences. You have to be able to stand 10,000 of the dumbest worst people you’ve ever met screaming at you and calling you a pedophile, and telling you that you deserve to be executed via electric chair. You have to be ready for the global news to pick you up. Tabloids in Serbia and Croatia and Italy and France and fucking Mongolia picked up the story about J.K. Rowling dying in Manhunt. I don’t think any of them got any details right. but it certainly got people mad at me.

It’s stressful, it’s annoying and I think it’s a real shame that any trans woman who isn’t a steel clad bitch who can grit her teeth through that gets shut out of the creative field by default. We have lost so many great creative minds and so many fantastic books and films and video games. But the fault falls squarely not just at TERFs’ feet, but at trans people’s feet. We are far too cannibalistic about our own artists. We need to line the fuck up and give people the benefit of the doubt.

ZL: One of the things that the book is so good about is writing into not just these complex intimacies of trans embodiment, but depicting other kinds of marginalized bodies as well. It’s a book that’s very diverse in terms of who is featured in it and who the main characters are, in a way that bucks against the typical white, straight, thin milieu characteristic in most apocalypse novels.

More specifically, Indi, as a fat character, is described in such loving, intimate detail, and I realized as I was reading her how rarely characters with bodies like hers appear described like she is in the books I’ve read. And she’s allowed to be sexual! (Although, of course, so much of the sex in the book is deeply complicated.) But at the same time, the book doesn’t shy away from the fatphobia she encounters or internalizes. Not sugarcoating that seems like an act of care, too. How did you balance these two impulses in writing Indi?

GFM: Writing novels is something I’ve been doing since I was 14. I’ve got an entire sheaf of books that no one will ever read, and through this process I have continually pushed myself into places of discomfort to write about types of people and types of bodies that I was uncomfortable with. In this case I wanted very badly to push past my resistance to writing a character with a body like mine.

Indi is really fat. There’s no escaping that facet of her identity in her existence, and to write about that honestly, I was both pushing myself and challenging myself to be more connected to that part of my existence which has always been very important to me, but which I have frequently hidden myself from, because it’s often too painful or too complicated to deal with in the moment.

I’ve been fat for my adult life, almost all of it, and most of my partners have been fat. Those are the bodies that I love.

And also, like you said, it’s an act of care, because applying practice to these bodies, and giving them that descriptive attention and depicting people with these bodies moving through the world, and experiencing what all of us experience—love and disappointment and quandaries and confusion—it’s humanizing not just in a general sense, but on a personal level. I would say that writing Indi helped me feel like more of a human being. I’ve been fat for my adult life, almost all of it, and most of my partners have been fat. Those are the bodies that I love, and the bodies that I try very hard to prioritize in my life. I wanted to reflect that in my creative practice, too,

ZL: I wanted to end by asking more about prioritizing love in your writing. I think it is really extraordinary how much care is clearly present—in the characters’ relationships to each other, but also in how the book is written, even as it’s also scary and fucking gross and intense.

Throughout the whole book, death, disability, and debility are so present—but there’s also such an emphasis on the importance of loving as damaged queer people. Even at the end of the book, after this whole fraught relationship with Fran, Beth still cries over her as she’s dying and tells her that she loves her. The book ends with them together. Was that intimacy always a part of the book?

GFM: Yeah, right from the beginning. I don’t think there’s any book without that relationship. [The love in the relationship between Fran and Beth] is the core of everything that happens in the narrative, and that’s life too.

You know, my grandmother died a couple of months ago, and we had a tough relationship. She was a difficult woman. She had an unmanaged personality disorder, and she could be bitterly negative and kind of a black hole. But she was a great artist, and she loved me the best way that she could.

And when I was at her bedside as she was rapidly deteriorating, I didn’t think about, oh, that time she’d been shitty to me, or ignored something I’d accomplished. I thought about how I loved this woman, and she had loved me, and we had spent that time with each other and shared so much.

Human beings are fucking monkeys that want to be with the other monkeys, and that entails a certain amount of suffering and difficulty, even from the people you’ll come to love. At some point in everyone’s life you’re gonna hold someone who has been a piece of shit to you, and you’re gonna say I love you and you’re gonna mean it, and carry that grief with you for the rest of your life.