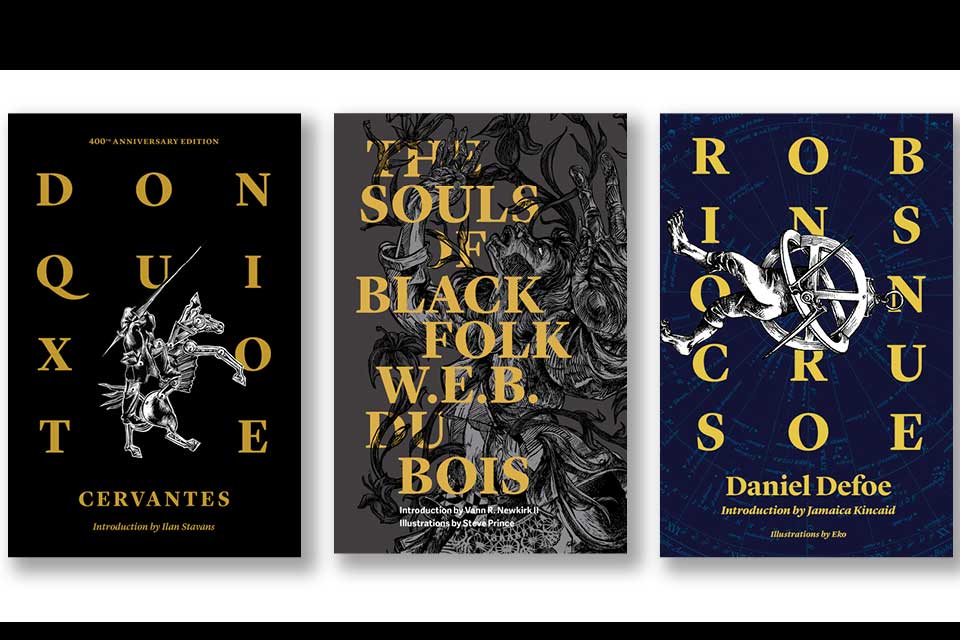

Since 2015, award-winning Restless Books publisher Ilan Stavans has been immersed in bringing the literary classics to new audiences through Restless Classics. These editions come with introductions by prominent diverse writers from around the world—Jamaica Kincaid for Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, Lauren Groff for Virginia Woolf’s Night and Day, Boris Fishman for Chekhov: Stories for Our Time, or Francine Prose for Frankenstein—and illustrations by a cadre of international artists like Eko and Keren Katz. They are geared toward young and often underserved audiences through programs like Classics Behind Bars, which brings them to incarcerated readers, and Restless Reads: A Virtual Classics Book Club, offered in conjunction with the New York Public Library. The following electronic conversation took place in April 2021.

Jenna Tang: For starters, could you define what a literary classic means for you?

Ilan Stavans: A literary classic is a book that knows how to be patient, a book with all the time on its hands, capable of waiting for the right readers to come by. It is also a book that “survives” translation. The classics are always in the process of being retranslated, in part because they are in the public domain but also because language ages, which prompts us to refashion them under a fresh new look. Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, for example, has been rendered into English thirteen times; Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, eighteen times; and Cervantes’ Don Quixote of La Mancha, twenty-two times. Needless to say, when looked at comparatively, the quality of all those translations is, well, unequal. But regardless how atrocious a translation might be, the original survives.

Translators are always pitching new versions as a way to supersede the inefficacies of their predecessors, only to produce, of course, equally inefficacious versions. And new publishers are investing again in the classics because their appeal is perennial. As much as I hate looking at literature as a market commodity, it is ruled by supply and demand. I like what Giancarlo DiTrapano, the late publisher of Tyrant Books, told the magazine Entropy in 2015: “Tyrant stuff isn’t for everyone, but nothing should be for everyone. Or at least nothing that’s worth anything. You know what’s for everyone? Water. Water is for everyone. And if you’re publishing something for everyone, well, you’re publishing water.”

Tang: Can you recall what was the very first classic title you read?

Stavans: A fascinating question. I don’t know at what precise moment I became aware of the concept of a literary classic. The first time I read The Little Prince? At the age of eight, it came with a strong endorsement from my mother. But I don’t remember being interested in it. I wasn’t into reading; I preferred outdoor activities. The illustrations seemed childish to me. To be honest, the narrative still feels infantile. Clearly, I didn’t get the allegorical nature of classics. The little prince wasn’t Everyman, a mythological hero in the middle of a journey. I needed to grow up to realize that the book was, well, more than just a book: it was a canvas on which readers could project themselves. That’s what classics are: more than just an accumulation of pages, they are the stuff our personal dreams are made of.

I’ve now translated Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s volume into Spanglish, which to me is a way to say thank you. But, frankly, it is peripheral to me in comparison with the Hebrew Bible. That’s the ur-text. I feel Noah’s ark, the Tower of Babel, the story of Abraham’s calling, Isaac’s Akedah, and Jacob’s ordeal and Moses’ liberation odyssey are imprinted in my DNA. I come from a Jewish-Mexican family in which culture was a form of religion. If pressed, I confess not to remember a specific moment during which I read Genesis. But that’s what the classics are: we get them not through reading but by osmosis.

That’s what classics are: more than just an accumulation of pages, they are the stuff our personal dreams are made of.

Tang: It’s important to think of the classics that have influenced us throughout our upbringings. What brought you to start the Restless Classics imprint? You switched from being an author to becoming a publisher. Was that switch challenging? What prompted it? Is there something specific you look for in world classics?

Stavans: Independent, nonprofit publishers are devoted to bringing out cutting-edge books. Restless Books is devoted to extraordinary literature in translation. It also focuses on giving immigrant voices a platform. I was about to reach fifty—that is, ripe for a midlife crisis, or as Dante would put it in the Divine Comedy, “Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / mi ritrovai per una selva oscura / ché la diritta via era smarrita”—when, during an interview about translation on NPR, I spoke about the dire number of books that come from other languages and are published in English. It was a comment frequently made in public. After the show, the host asked me if I got tired of my message and if I ever thought of doing something concrete about it.

That might have been the seed for the project. I decided I would either commit myself to a publishing venture or find a new message. In the next few months I talked to several potential funders. I found in one of them an extraordinary partner. She challenged me to educate myself by becoming a student again, taking a business course on startups. After taking one, a financial plan was devised. That happened in 2012. Restless Books was launched the following year, first as a for-profit. Honestly, I didn’t think the endeavor would go beyond a year, maximum two. One of my models was James Laughlin, who launched New Directions while a student at Harvard in 1936 with money from his father, out of a cottage at his aunt’s home in Norfolk, Connecticut, and stored copies in his college room.

We live in different times, though. For one thing, the market is now astonishingly crowded. Maybe it’s my teacher’s self, but I believe it is incumbent upon publishers not just to release books but to help open them in front of audiences in need. If these are perennials, let their durability, in affordable prices, reach segments of our culture frequently left behind. Isn’t that the dream of democracy, to allow its dwellers to have a voice? The only way to achieve that is to allow them to appreciate the voices of the past. Penguin Classics and Oxford Classics, obviously, have set the path. As a scholar, I am part of their backlist.

But the classics shouldn’t be their exclusive purview alone. This essential field of literature needs a jolt. Independent publishers must push in further, more adventurous directions. Reading Frankenstein in prison is a unique experience. After all, we see those behind bars as monsters. What do “monsters” think of monstrosity? Or give immigrants Don Quixote. Is there a better book about dreaming oneself into a new life? What I look for in the classics is a message that is reinvented every time a new reader opens it. Along with the author, it is the role of the introducer and artist to make a case for that fresh take.

Give immigrants Don Quixote. Is there a better book about dreaming oneself into a new life?

Tang: Can you talk about your experiences collaborating with translators to bring more classics to English-speaking audiences?

Stavans: At Restless Classics we take two approaches. One is to revive a translation that has circulated but still commands attention. Reading a classic, I believe, ought to entail an element of foreignness. If you delve into Les Misérables in French, you cannot fail to first recognize, and then, hopefully, to thrive in, the somewhat stilted nature of Victor Hugo’s language. Classics are windows into an epoch, not only in content but in form. That’s where their allure is found. I don’t think translations should turn them into modern artifacts; the feeling of alienation felt in the original should be accessible in the translation as well. But we also commission new translations of classics that either have failed to “arrive” in English, or the available translations of them aren’t in the public domain.

Tang: Having published so many works in translation across cultures, what are the most urgent questions you think publishers should be asking themselves? What change do you see in the world of publishing translated literature?

Stavans: It is crucial that, as culture seeks to represent nonwhite voices, our conception of perennial literature undergoes an expansion. We need to make classics from Asia, Africa, and Latin America available to underrepresented readerships. That means recalibrating our definition of a literary classic and explicitly reaching out to translators for new, undiscovered classics. It also means that nonprofit, independent publishers, which are often strapped for money, need to build partnerships in order to subsidize these new translations. For instance, Restless Classics is about to bring out the first English translation ever of a nineteenth-century slave-narrative novella, The Maroons by Louis Timagène Houat, from Mauritius, translated by Aqiil Gopee.

By the way, I have noticed a distressing phenomenon. Copyright functions as a kind of censoring mechanism. Books that were published recently but failed to gain traction suffer in limbo, out of print but still under copyright, whereas books out of copyright are available to anyone. This means that titles released between, say, 1930 and 2010 are impossible to get other than in libraries.

Tang: The Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing was established in 2016 to honor debut fiction and nonfiction works by first-generation immigrants. Can you talk about starting this literary prize?

Stavans: The prize is awarded alternatively to a fiction and nonfiction winner. Restless Books has published Deepak Unnikrishnan’s Temporary People, Grace Talusan’s The Body Papers, and Priyanka Champaneri’s The City of Good Death. They all launched their careers with these books. We also publish the series The Face, in which diverse writers (Ruth Ozeki, Tash Aw, Chris Abani, et al.) use their face as a springboard to reflect on their identity. These are the classics of tomorrow, I hope. Du Bois, in The Souls of Black Folk, argued that the theme of the twentieth century was the color line. In my view, the theme of the twenty-first century is immigration. Everything rotates around it: climate change, Covid-19, populism from Trump to other “aspirational” dictators, global finance, etc. It is essential that our conversation opens up to alternative perspectives.

Tang: You also run a series of Immigrant Writing Workshops. What are some of the most important questions and discussions you’ve had?

Stavans: These workshops not only inform Restless Books’ mission but define it. Immigrants understand what it feels like to live in the margins, peripherally. My impression is that the syncopated dance between the center and the periphery is no longer what it used to be. The center today exists in a state of never-ending doubt, complicit in ancestral crimes that range from colonialism to appropriation. It is minorities who now set the tone of cultural change. They function as translators. The immigrant workshops are regularly offered through various branches of the New York Public Library, starting with the Midtown one, and, similarly, the Los Angeles Public Library.

Tang: Translation is not just about languages; it is about the “coming across” among cultures. How does one navigate the marriage of sensibilities between authors and translators? How do you consider gender, ethnicity, and other identities to foster a more balanced and diverse relationship among all the people who are bringing cross-cultural works to the world?

Translators have always been agents of change.

Stavans: Translators have always been agents of change. The Muslim translators of the School in Toledo, in the twelfth century, for example, and later on under Alfonso El Sabio, brought Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Hippocrates into Europe. Or Lucretius’s De rerum natura. Without these translators, there would not be a connection with the classical past. Borges has an inspiring story, “Averroes’ Search,” about ibn-Rushd tendering in Arabic a couple of terms from Aristotle’s lost treatise on comedy.

Translators open the window to the past to welcome fresh air. They are surveyors of what is significant somewhere else and want to bring that significance home. As we make room for new voices from the world, we must diversify the database of translators. If and when they come from a diverse background, what they propose is likely to be more heterogeneous. A theater teacher of mine used to say to me that what’s important is not to give the audience what the audience wants but to teach the audience to want something else. A diverse army of translators will be able to achieve such an objective. The same goes for editors and, of course, publishers: we need otherness to be less alien.

We need otherness to be less alien.

Tang: Do the literary classics change over time? If so, what are the changes?

Stavans: They do, indeed. In two ways. First, one generation’s literary classics aren’t the same as those of previous or subsequent generations. As I mentioned before, we are currently in the midst of reimagining the classics, making the canon more expansive, less white and Eurocentric. Some titles fall off the shelf as others arrive. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for instance, is, it appears to me, less current than it was a few decades ago. I taught it a couple of years ago, and students found plenty to fault and that is difficult to justify these days.

At the same time, the work of immigrant writers—I love the novels by Viet Thanh Nguyen, for instance—is opening new vistas. This is as it should be. Literature, at first sight, might feel static, but it is just the opposite: an organic expression of a particular time and place.

The second change has to do with each and every one of its readers. The relationship we develop with a classic is like a lifelong friendship: it goes through ups and downs. Whenever we reopen the book, we are different, and, as a result, what we read is too. This, I think, is another definition of a literary classic: like a mirror, it reflects what is in front of it.

We not only open the classics to re-create the past; we also use them to calibrate the present.

Tang: What is the future of the classics in translation?

Stavans: The future is plentiful. As long as there are readers, literary classics will be in circulation in refashioned versions. The originals are sacred. Taking out a single word of the Hebrew Bible amounts to anathema since we’re talking about a narrative supposedly written by the divine. But no translator is godlike; on the contrary, all are miserably human, meaning imperfect in their quest. Therefore, the practice of translation exists, as it should, in a state of constant renewal. Without the classics, we are a tabula rasa: we have no memory. We not only open the classics to re-create the past; we also use them to calibrate the present.

Look at Shakespeare. I dream of doing a Restless Shakespeare; in fact, the name of this series is already a mission statement. There is arguably no more reprinted author in the English language. Do we need another Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, King Lear, and The Tempest? No doubt we do. He is a kaleidoscope that fluctuates depending on who is looking through it. There is the Elizabethan Shakespeare, the Victorian, the modern, the postmodern, the postcolonial, and so on. And there is also a restless Shakespeare, capable of conveying the perspective of a world always in transit and reorganized at all times—and at all costs—by outsiders. That’s the Shakespeare I’m after, one that lives in English but becomes an emblem of a world without a center.

May 2021