Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

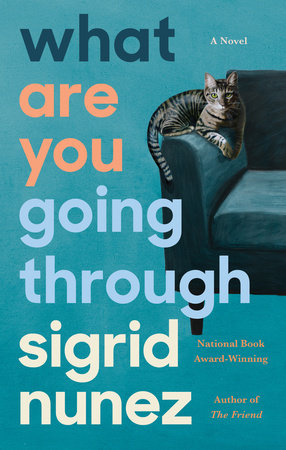

Sigrid Nunez’s latest novel, What Are You Going Through?, explores the rich interior life of a narrator whose name we never learn. She has a series of frank and meandering chats, some in her head, some with people; her Airbnb host, an ailing friend, a woman at her gym. Often she listens in on the people around her; a lecturer giving a fatalistic talk on climate change and capitalism, a mourning father and daughter at a café. The talks are about everything and nothing so the book is initially deceptively breezy. Until, that is, her ill friend—who’s been receiving cancer treatment at a local hospital—surprises her with a request: she wants help ending her life. This friend request closes out the first of the book’s three parts. Its weight and abruptness help transform the book from a casual read into a deeply empathetic study of the two women’s friendship and of the elaborate matrix of human connection.

This new book follows on the heels of her last book, The Friend, for which Nunez won the 2018 National Book Award. The Friend was widely praised for its unflinching and elegant three-pronged interrogation of grief, death, and friendship. In this follow-up Nunez again probes the depths of our fears about death and our desires for companionship. What does it mean to love your neighbor? Do we ever really have control over our lives? In What Are You Going Through?, Nunez mines a single complicated relationship for the truth of it all and endows us with many possible answers.

I had the opportunity to speak with Nunez over the phone in August. We discussed the perennial nature of human suffering, how she’s inspired by eavesdropping on strangers, and why her writing will never be perfect.

Naomi Elias: The book’s title is pulled from an essay written by Simone Weil in Waiting For God. Where did you first encounter the quote and why did it speak to you?

Sigrid Nunez: I’ve known about it for many years and it just was something that really rang true to me when I first heard it and still does. Her definition of what it would mean to love your neighbor would be to really listen to that person and ask them, “What are you going through? What is your trouble?”

NE: Between this forced quarantine and the global protests this year has helped put in clear relief who is capable of compassion and who isn’t. It feels like the release of this book and the questions it’s asking about the function of companionship and acts of service couldn’t be more perfectly timed.

SN: Well, I guess that might be true except the idea is that actually, you know, it’s always true because people are always going through this part of the human experience. You might not necessarily notice it but you’re surrounded by people who are living an ordinary life but they’re suffering from something; loneliness, or someone they know is ill, or they don’t have whatever they need. I guess we’re living in a time that feels intense because there’s such a focus on people suffering but really it’s always there.

NE: Right, I just mean, it’s going to feel more relevant to people because I feel like the question of what we owe to each other is very en vogue especially in pop culture. A book with the same title, What We Owe Each Other, by the philosopher T.M. Scanlon was the inspiration for Mike Schur’s very popular television show The Good Place and I think impending ecological collapse and all the protesting has kind of forced more people to reevaluate their lives and their connections to each other.

SN: Yeah, I agree.

NE: This isn’t a book about death but rather a book about the questions we have when faced with our mortality and the self-audit the narrator starts to do of her life. You explore those questions through conversations the narrator has with other people. It’s loose in the way conversations have a loose flow but the book still feels structured. How did you outline the conversations and the book itself?

SN: I wrote this book in exactly the same way that I’ve written every book that I’ve written. I don’t actually outline it or structure it ahead of time. That never felt natural to me. Although I know many writers who do do that. What I do is I gotta start somewhere so I just jump in with something. In this case, I decided to start with “I went to hear a man give a talk” and then, you know well, about what? Where? What? Where is she? Is she alone? I can start storytelling and then things flow into place.

I take certain things from life in that some of those conversations are from eavesdropping. In the bar early on where a woman and her father are talking about the mother who had died a year before, that was something that I heard many years ago and I was struck by that and how this young woman was desperately trying to get her father to focus on her pain at that moment and he just wouldn’t do it. He was just saying, well, your mother really suffered. Well, I remember she said she suffered. But she kept saying, I know dad, but I’m trying to tell you that I too need some attention here. I take things from life and I also invent things. Then at a certain point the options narrow down. You can’t just do whatever you want. You have to finish what you started, you have to make some connections. When it’s finished, then I see it should be in this three-part structure, these are the natural breaks. But none of this is actually planned beforehand. It all happens in the process.

NE: In the first part of the book you slip into different perspectives including the perspective of the house cat owned by the narrator’s Airbnb host. Was that fun? Was going into a cat’s perspective a way to explore commonalities between what humans and animals are seeking from the world or am I reading too much into it?

We’re living in a time that feels intense because there’s such a focus on people suffering but really it’s always there.

SN: It’s a little bit of a tricky thing because I don’t really like when animals speak because they don’t really speak. But in this case, she’s in bed and the cat jumps on the bed and she’s going to sleep and so it’s kind of unclear. I mean, is she dreaming? In the morning she says the cat told a lot of stories last night but this is the only one I remembered when I woke up. So it is unclear whether or not that’s a real cat or that’s a dream. But I did feel that if you put yourself into the mind of an animal, particularly a domesticated animal, it’s not hard to imagine how they could tell their story. If the rescue cat could tell their story it might come out like this. It seems like a true history for that cat for me, the idea that it would be happy now with this second mother but that it was taken away from its mother and that that was kind of traumatic. So that’s where that came from. It was fun to write. It was hard to write. It was actually much harder to write than I thought it would be. I struggled with that passage. I think in the end I liked the idea of having an animal represented. I thought that maybe it wouldn’t work or be too much. I thought, well, I have an editor, I have an agent, I have other people who read this before it gets published. If they think it doesn’t work or it’s too much, they’ll say, ‘I think you should get rid of that.’ And I would have done so. But everybody seems to love the cat!

NE: For me, I wasn’t prepared for it but I certainly thought it was interesting. So many people wish they could talk to their pet so I feel like that’s a relatable thing.

SN: Right!

NE: Switching gears a little bit, the book touches on the idea of assisted dying which is illegal in nearly every state in the U.S. The book doesn’t seem to take a side either way. Is it something you hoped to start a conversation about?

SN: I think the conversation has started. I think people talk about it quite a bit. I didn’t think I was really opening up anything new there. I do think it’s a problem. I mean, it’s a huge problem because people don’t seem to know how to talk about it. We seem to be at an impasse. But I don’t really have any answers about it myself. One of the concerns of the medical establishment is how much resources are used for people at the end of their lives in the hospital. That’s not a good thing for the medical world. It’s just the way we do it. We make all these efforts at the end of life to keep somebody alive who in some cases does not really want that to happen, it’s their family that wants it to happen or in cases where it’s not really buying them very much, it’s buying them [time] at the cost of a really terrible prolonged suffering. But it’s just the way our culture is set up that you do everything you can to keep the person alive. There are plenty of people who feel that that’s not the best thing for the dying person, and it’s not the best thing for the people who love that person, and it’s not the best thing for the medical establishment.

NE: Would you feel comfortable saying whether you support it or not?

SN: I certainly do support it. I mean, it’s up to the individual. But if I were aware that somebody had made the decision because their situation is absolutely terminal and they are aware of that and that rather than going through a long, prolonged period of suffering, they would rather have a euthanasia drug, certainly I would support that decision. I would respect that decision. I would understand it completely.

NE: It prompted me to look into the death with dignity laws because it’s not something that I’ve thought a lot about but it was interesting to hear different perspectives on it.

Often we say ‘words fail me’ or fall back on hideous clichés like ‘I’m sorry for your loss.’ None of it is really adequate. So where are the words that you’d feel really captures it?

SN: Yeah, Death With Dignity, and there’s also an organization called Compassionate Care I think. There are quite a few. There’s a certain amount of activism about this cause. It’s complicated because of course, I see how certain people are afraid that if you make it too easy that then people would pressure people into dying more quickly. Of course that’s a frightening thing.

NE: I was struck by something the narrator says in the book—“every love story is a ghost story.” Is that something you believe?

SN: I think that’s the title of the David Foster Wallace biography.

NE: Oh ok, I’m looking it up. Yes, Every Love Story is A Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace. So have you read that book? Is that where you got the line?

SN: Well, I got the line from the title. I actually haven’t read the biography, but that’s what she’s referring to when she says that. I do have a friend who once said, “every story worth telling is a love story.” I think that’s a beautiful quote and I actually used it as the first sentence of a story that I once wrote. I wrote “every story worth telling is a love story but this is not that story.” I love that.

NE: The narrator throws away the idea of journaling the experience she has with her friend because she says “language would end up falsifying everything, as language always does.” Do you as a writer ever feel you’ve written exactly what you wanted to write, as truthfully and faithfully as you intended? Or is the end result always a compromise?

SN: I think there’s pretty much always that anxiety that it’s always a little bit to the left or the right of what the thing really is. We have language but very often we say “words fail me” or we fall back on hideous clichés like “I’m sorry for your loss.” None of it is really adequate. So where are the words, where is the language that you’d feel really captures it? It’s a very familiar feeling for any writer, the frustration of, well, I’m doing the best I can but I realize that I’ll always be missing the mark because language is so imperfect.